Three challenges facing free-range egg producers

Getting the best from free-range layers requires careful feed management, as Ken Randall reports

Free-range egg producers face three main feeding challenges to get the best from their flocks – achieving the correct bodyweight, controlling egg weight and minimising mortality.

According to Fabien Galea, technical manager with Dutch layer breeder ISA Poultry, free-range birds are generally under more physical pressure than cage birds, particularly at the start of lay, and this can lead to flock unevenness and reduced performance.

“The challenge to getting the best results is to feed and manage the weakest birds and to keep the flock as even as possible,” he says.

BODYWEIGHT

When it comes to bodyweight, it is important to recognise that there are three phases of the laying cycle, Mr Galea explains, and maintaining the correct bodyweight is essential at each (see box).

“The goal is to have enough energy intake to ensure maintenance, production and growth. Poor bodyweight leads to weak birds, which are more susceptible to disease and to lowered production.”

There are three main ways to manipulate the energy intake of the bird, he explains.

The first is to control the energy concentration of the diet. In practice, feed consumption drops as metabolisable energy (ME) rises, but not at the same rate, so that, overall, energy intake rises as ME rises.

“The recommended programme is to use a high energy diet at the beginning of lay (11.5-12MJ/kg), adjusted according to the average bodyweight in the flock.”

After 30 weeks, continue to weigh birds and adjust the energy level to the target weight, he advises. Avoid birds getting too fat, as they have a higher energy requirement just for maintenance, he adds. And pay particular attention to amino acid balance.

THE THREE STAGES OF EGG PRODUCTION * First stage – laying begins, egg weight increases and limiting feed intake keeps body weight down. * Second stage – there is a small and slow decline in egg production. * Third stage – time to work on the energy intake of the bird to increase bodyweight and sustain egg numbers. |

|---|

The second factor affecting bodyweight is feed particle size. “Birds prefer bigger particles,” says Mr Galea. “If particles are too fine, there is under-consumption. If too coarse, there is sorting by birds and the flock loses heterogeneity. A good crumb feed can help to increase energy intake.”

Thirdly, the timing of feeding plays an important role. “Don’t feed more frequently in an attempt to increase feed intake, it won’t solve your problems,” Mr Galea advises.

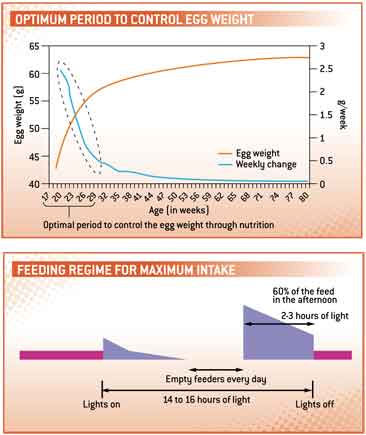

Frequent, smaller feeds only lead to an accumulation of smaller particles, which may be left uneaten. The answer is to distribute 60% of the daily feed two-to-three hours before lights off. Then, at lights on, birds are hungry and are forced to eat the small particles left over. In the middle of the day, feeders should be left empty for one to one-and-a-half hours, which is not something managers normally like to see, says Mr Galea (see diagram 1 on Feeding Regime).

The same feeding schedule can be adapted to the pullet rearing stage as well. This regime encourages natural feeding behaviour, so birds eat their requirement for the night period in good time, as well as aiding development of the crop through the need to store feed.

EGG WEIGHT CONTROL

The second major challenge is controlling egg weight.

This is achieved primarily though bodyweight management, the nutritional composition of the diet and control of feed consumption.

The main issue is the bird’s bodyweight when the first egg is laid. This is a strong indicator of the ensuing average egg weight during lay, with larger birds laying heavier eggs (see table on pullet weights).

The lighting programme needs to be adjusted according to the target egg weight so that the birds do not come into lay too soon or too late. Light stimulation should be carried out in response to bodyweight, rather than age.

With nutrition, the optimal period to control egg weight is from 18-28 weeks. After that it is either too late, or the nutritional response is lower (see diagram 2 on egg weight change).

The most effective nutritional factor is total fat content of the diet. Saturated fatty acids have little or no effect on egg weight, but unsaturated fats do. Linoleic acids are the most effective, and need to be above 1.2% of the diet to do this.

Amino acids are also critical, and methionine is the most effective to control egg weight, but egg numbers may be reduced if the levels are taken too low.

Because nutrient intake is a function of both consumption and feed concentration, control of consumption is paramount when trying to influence egg weight.

Installing a weighing scale in the free-range building makes it possible to measure feed consumption accurately. This can help control both egg weight and, at the end of lay, bodyweight by preventing over-consumption.

There is also a strong relationship between egg weight and egg number, with 62.5-63.5g the optimal range for maximum production. Below and above, egg numbers fall away.

“The best solution is to have a medium bodyweight at first egg, and then increase egg weight through nutrition,” says Mr Galea.

The main principles to bear in mind are that, although increasing egg weight is possible – mostly during the first phase of lay – decreasing it is impossible. And when egg weight is controlled at the end of the laying period, it usually leads to a fall in egg numbers.

LIVEABILITY AND FEATHERING

The third key challenge for the free-range sector is to minimise mortality and maintain feathering.

In this, insoluble fibre such as cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin can play a part. These components have no or minimal effect nutritionally, but do have a major role in the composition of the droppings, and also accelerate intestinal transit.

However, they also have other valuable effects on feathering and liveability.

In one trial, a diet enriched with insoluble fibre reduced mortality compared with controls. Raising the fibre level from 3.6% to 5.1% by the addition of sunflower meal reduced mortality from 7.4% to zero.

However, feed consumption declined by about 3g/day and, with energy levels constant, egg mass dropped by about 1g/day.

Adding coarse fibre to the diet can also control feather pecking. In one trial, the addition of coarse oat hulls reduced the feathers in the gizzard contents from 0.47g/gramme dry matter to just 0.02g/gramme dry matter compared with controls.

A practical recommendation for providing insoluble fibre is to supply free range, and also barn flocks, with wood shavings or chopped straw.

But do not introduce straw or wood shavings just after population or there is a risk of floor eggs, Mr Galea warns.

EFFECTS OF EXTRA FIBRE * Increases the time spent feeding * Increases time that feed spends in the gizzard * Improves starch digestibility * Reduces consumption of feathers * Improves feathering and liveability of the flock TOP TIPS FOR FEED MANAGEMENT * Control bodyweight using: Energy content of the diet Feed particle size Feeding technique * Control egg weight using: Body weight at first egg (lighter bird for smaller egg size) Adjust fat concentration of the diet, the type of fat, and at the end of lay, amino acids concentration Control/ manage feed consumption * Provide insoluble fibre to free range bird (eg chopped straw) |

|---|