Guidance on keeping safe when TB testing cattle

In 2013 two farmers were killed by cattle during TB testing and with around 1,700 tests being carried out a week in Great Britain, the threat of accidents while handling cattle is high.

Testing increases the possibility of cattle becoming agitated from the handling and for some it will be their first time in a crush.

Vets and farmers can face serious injury unless steps are taken to mitigate the risk at this very stressful time.

Modifying existing handling facilities to take into account animal behaviour can reduce stress for both cattle and handlers, as well as improve safety during TB testing.

Two farmworkers are killed and more than 100 are injured on average every year by cattle, according to HSE figures.

Almost half of these injuries are caused by inadequate handling facilities, says HSE inspector Tony Mitchell.

However, he believes this figure could be much higher because anecdotal evidence suggests that a large number of injuries go unreported.

“There are also large numbers of minor incidents and near misses that we do not hear about and many serious accidents are not reported to the HSE,” says Mr Mitchell.

“For example, there have been several studies into livestock accidents that suggest up to 24% of producers are injured every year.

“And what’s more, if you have had one injury, you are three times more likely to have another.”

A vet based in the West Country – a TB hotspot area – who did not wish to be named, says his practice conducts up to 600 on-farm TB tests each year.

“Up to 50% of our herds can be under restriction at any one time,” he says. But he believes at least 20% of the herds visited by the practice have dangerous handling facilities. These are typically at smaller herds that haven’t updated their facilities for some time.

“About 50% of the systems wouldn’t be fit for purpose, but only 20% would be dangerous.” However, this is still too many, he adds.

The main hazards include:

- Inadequate restriction of animals

- Having to test dairy cows in herringbone parlours

- Makeshift pens of gates and string of inadequate size for stock

- Complete absence of restriction.

Crushes that are in need of serious attention are the most common hazard, he says.

The least common is a complete absence of any restraining facility, but he has visited small herds where animals are expected to be tame enough to be presented for testing without any restraint whatsoever.

“It is pretty farcical. You end up in a situation that puts both animal and human health at risk,” he says.

He has suffered injuries handling cattle. But, to date these have luckily, not been serious. “I have broken a number of fingers and received a couple of nasty kicks,” he explains.

“The worst example I saw was where a workman was kicked in the arm by a cow through the side of a gate and broke his arm.”

With TB testing now common on many holdings, he believes it should be a wake-up call for farmers to take stock of their facilities.

“I think it is essential for every farmer to have the ability to handle animals in a safe way, that’s irrespective of TB testing,” he says.

“But with TB spreading further north there will be some farmers who don’t handle their cattle very often, and that can present a challenge.

“Farmers should assess their facilities and see if they are fit for purpose or whether they need to be improved or replaced.”

Let’s face it, no one looks forward to TB test day, but making sure handling facilities are set up to maximise cattle flow could help the task go a lot smoother.

All too often, a poor handling set-up is the main cause of stress to both staff and cattle during TB testing, with agitation increasing the likelihood of things going wrong and people getting injured.

Any stressful event can also affect cattle health, leading to reduced immunity, poor growth rates and reduced carcass quality at slaughter.

However, regardless of how many animals are being handled, there are ways to tweak the existing set-up to improve efficiency and safety.

Simon Turner from Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) says the key is to work with cattle’s natural behaviour to encourage calm flow. This will also remove the need for the handler to come into direct contact with the animal, thus improving safety.

“Systems cobbled together as temporary fixtures are commonly associated with things going wrong. That’s the reason to have properly designed systems,” says Dr Turner.

“Facilities don’t have to be big and pretty to work well, they just need to be designed right and strong.”

To ensure handling systems are working efficiently, Ian Ohnstad from the Dairy Group says farmers should stand back and watch how stock move through the system.

“See where cattle back up and where they are comfortable. If staff are having to routinely yell, then it’s not right.”

Collecting pen and forcing pen

Handling facilities will generally consist of a holding pen, forcing area, race, crush and dispersal area. Often, too big a collecting pen is the cause of issues on farm.

Dr Turner advocates farmers opting for longer, more rectangular shaped pens with cattle being funnelled down into the forcing area from one side rather than two. A collecting pen of about 4.5m in width is ideal. Having a sweep gate can also enable handlers to encourage cattle to move safely from behind the gate.

Producers should also avoid putting too many animals into the force pen at the same time, as this can create issues with overcrowding, preventing animals from being able to orient themselves. This can mean handlers are more tempted to put themselves at risk trying to get them to move.

Vet Paula Hunt from Synergy Farm Health says making the most of cattle’s tendencies to go back in the same direction they’ve come from can also aid flow. This may involve using a Bud Box (see diagram, Case study tab).

To make it clear to cattle which direction they need to travel, Dr Turner suggests using solid sides as much as possible, particularly on the force gate and along races. This can be easily achieved by using wooden boards or any other material that will act as a visual barrier.

Races

Introducing a curved, sheeted race can also aid flow, as it cuts down the sight of the handler and crush.

“It doesn’t need to be big and fantastic. Just a gentle S-shape can help hide the crush,” says Dr Turner.

For example, on a system with a straight race along a wall, curving the race out slightly from the wall for 2m and back in can help improve flow. This can be achieved by using straight, well-secured gates to form a stepped curve. Alternatively, metal sheets or plastic can be wrapped around secured posts.

“Temple Grandin [a US animal behaviourist] suggests a 2-3m [6-10ft] straight length after the force pen, before the curve. This is particularly important if you’re going into a tight radius curve,” says Dr Turner.

He says the golden rule is not making the straight section after the curve and before the crush too long, or you lose the benefit of the curve. Ideally this part should be the length of two animals.

It is also worth ensuring races are high enough at about 1.6-1.8m (5-6ft) to prevent cattle from climbing out. A 0.3-0.4m (1-1.5ft) wide external catwalk can then be easily built so handlers can access cattle safely from above. This stops handlers being tempted to put arms between bars to push cattle forward, which can cause injury.

Crush

Ensuring the crush itself, gates and animals being handled are well secured is crucial to avoid handler risk (see cattle handling safety tips below).

Miss Hunt also emphasises the importance of an escape route. “Never put yourself between the crush and a wall – it’s surprising how often I see farmers take those risks,” she says.

To encourage flow into the crush, noise should also be limited. Consider putting heavy-duty rubber strips between metal in the crush. There should also be more than 6m of clear space after the crush exit to encourage flow.

Mr Ohnstad explains how cattle’s poor depth perception also means consistency of light and level of illumination are both important for cattle flow, with cattle having a tendency to move towards light.

“One of cattle’s greatest fears is slipping, so make sure the floor is clean and non-slip and wash it before handling. If concrete isn’t grooved, consider throwing some sand down,” he says.

Hiring facilities

Hiring mobile handling facilities can be a practical way to improve handling set-up for those who don’t want to invest themselves.

Andrew Mear from Livestock Services Portable Cattle Handling says 75% of his work is TB testing. His handling system was designed for cattle flow and includes a semicircular forcing pen with a sweep gate.

“About 80% of the farmers I work with are older than 60 and struggle on their own. It means they get full access to the [handling] kit and my help. It works out quick and effective and no one gets hurt,” he says.

Miss Hunt says mobile systems can be particularly useful on farms that have groups of stock in different places or when cattle are at grass, but it’s crucial the set-up is secured well either to a wall or the ground for maximum safety.

Top tips for safe cattle handling

- A circular collecting pen means staff can stand safely behind a forcing gate as they move animals

- Ensure doors are operated from the working side of the race so the operator doesn’t have to reach across to close them

- Never work on an animal in the crush with an unsecured animal behind it

- Secure the crush to the ground

- In the crush, always use a rump rail, chain or bar to minimise movement

- Don’t put hands in between bars

- Never position yourself between a moving gate and wall

- Don’t use makeshift gates and hurdles – it will make handling difficult and increase injury risk

Caroline Spencer – Volis Farm, Hestercombe, Somerset

Designing a cattle handling system that makes the most of cattle’s natural instincts means TB testing heifers is a “quiet and pleasurable experience” for the team at Volis Farm, Hestercombe.

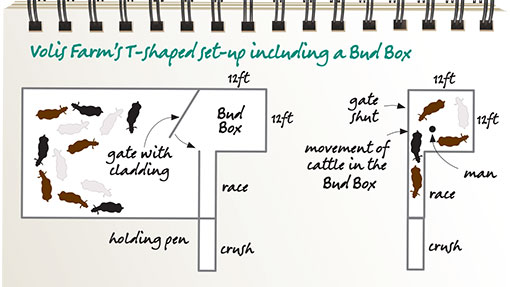

Somerset dairy farmer Caroline Spencer uses a set template to handle stock away from the main farm. This uses a T-shaped set-up that incorporates a Bud Box – named after the American designer Bud Williams – to naturally draw cattle up through the race.

Cattle are moved in small batches from the collecting pen into the Bud Box, which is a normal gated pen measuring 3.6×3.6m (12x12ft). As they enter the box, they pass across the front of the race entrance. When they reach the back of the box they turn back in the direction they’ve just come.

In the meantime, the sheeted gate leading to the collecting pen has been shut. Cattle see the opening in the race and automatically go up to it to escape (see diagram below).

“Cattle take to it instantly and you never have to force them. You need fewer people to handle stock and risk [to handlers] is reduced, as cattle are calm,” says Mrs Spencer, who runs 280 Friesian cross Jerseys and rears all her own replacements.

Mrs Spencer has put in corner posts on winter and summer keep, allowing the gates and crush to be moved there whenever handling is necessary.

This system is generally used for any handling of seven- to 19-month-old heifers with cattle moved into the Bud Box from the collecting pen in groups of four to six. One person stands in the box to gently encourage the natural movement. Size of the box is crucial – too big and it won’t work.