What is the best grain marketing strategy for this season?

Grain marketing strategies are inevitably a hot topic of discussion at this time of year. Farmers clearing out their barns ready for the new season can compare notes on whether – or not – they made the best marketing decision, and how they are going to change their strategy for the coming year and the year after that.

But what is the best overall strategy? Does forward selling always outdo the spot market, or should farmers keep their powder dry until well after harvest to take advantage of short-term blips in price?

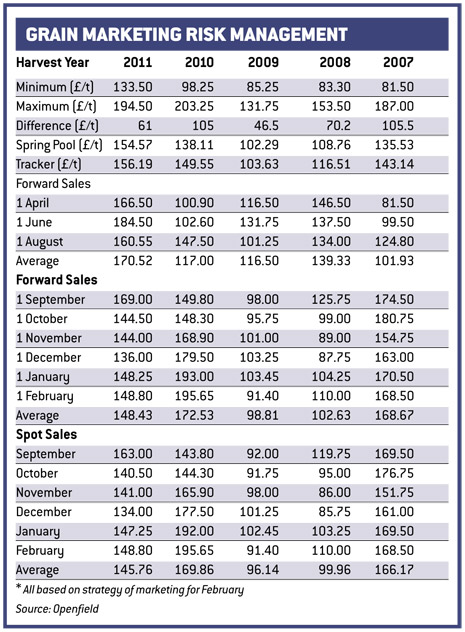

With the help of Richard Jenner, marketing manager at Openfield, we’ve compared ex-farm prices over the past five years to see if there is a noticeable difference in success with different marketing options.

Over the past five years, ex-farm wheat prices have fluctuated by an average of £78/t – and up to £105.50/t – between selling forward from April before harvest and moving grain in February the following year. Openfield’s spring pool, which markets grain over a whole year as a managed fund, for movement between January and March, would have averaged almost £155/t last year.

A tracker, which is equivalent to selling an equal quantity every day between April and February, would have averaged £156. Over the past five years the difference has been similarly marginal, with the tracker netting an average gain of £6/t.

Those farmers who sold their wheat forward for February movement in three tranches before harvest – on the first trading day of April, June and August – would have averaged an ex-farm price of £170.52/t last year, based on the closing futures price on that day – a good £14/t ahead of the tracker fund.

However, taken over the previous four years, they would have been better off in only half of those seasons. On average, over five years they would have been £4.75 a year richer by opting for the tracker fund.

Farmers who only sold their grain forward (for February movement) once they knew how much was in the barn would have achieved a similar result, beating the tracker and pre-harvest sales in two of the past five years.

On average, they would have been £4.41/t better off than opting for a tracker fund. Those who only sold on the spot market in each month from September to February would have achieved similar results, but with an annual gain of £1.80/t.

Anyone who held all sales back until February would also only have seen a benefit for two of the past five years. However, the net gain would have been the greatest, at £9 a year more than the tracker.

So is there really much to learn from this data? On average, over the past five years, farmers would have been £9/t better off selling spot for February movement than any form of selling forward.

However, those who read the market right in every year, and adopted the best strategy available within the data given, would have ended up an average gain of £44 a year.

Of course, picking the top of the market each year – potentially selling further forward or holding off until later in the season – will result in significantly larger gain, but the chances of doing that year after year are slim.

“Volatility is a fact of grain marketing that necessitates an integrated approach,” says Mr Jenner. “The best strategy varies quite considerably from year to year – what is important is to know your costs of production and to analyse your attitude to risk.

“The days of wheat markets moving up nicely by £1/t a month have gone – the intra-day movement now is considerable.”

Of course, locking into a minimum-priced option-based contract can allow farmers to make the most of market rises while eliminating risk. “But the difficulty is that options now cost about £20/t, which can be very off-putting compared with the actual price you could receive on the day.”

Graham Redman, partner at the Andersons Centre, agrees that trying to pick the correct marketing strategy from one year to the next is virtually impossible, as each year is different.

“Volatility from one year to the next can be extreme. But a farmer who can store grain and is good at spotting sales opportunities will have more chance of selling towards the higher end of the market than a spot seller who has to move grain at harvest time.”

There are some hidden trends in futures trading that can help farmers to plan their marketing strategy, he adds. “More often than not, the contract high and low come within a couple of weeks of the start or end of the contract period, following an overall trend up or down in the market.”

London wheat futures contracts open at least 24 months ahead – so May 2014 prices are already available. “You can sell the crop long before it is even drilled, so if you only sell on the spot market you are cutting out a huge swathe of marketing opportunities. But of course you need to be careful how much you sell forward, especially if the crop is vulnerable to being written off by adverse conditions.

“If you can see a profit margin it is worth locking in some forward sales, but even if you can’t see a margin, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you should hold off – prices may just drop even further.”

Of the past 15 years, 10 years were in a long-term bearish trend, says Mr Redman. “Those people who sold forward as soon as the futures contract came on the board would have been substantially better off than those who waited to sell on the spot market.”

In contrast, the past two or three years have followed a rising trend, so those who sold spot, at the end of the contract period, were better off than farmers who had sold forward. “If you can pick the general trend of the market, you can then formulate the best selling strategy.”

So where might the long-term trend be headed? “Over the majority of the bearish 10 years there were very large global stocks that were gradually being liquidated, due to a change in central governments’ mindsets that storing grain long term was too expensive,” says Mr Redman.

“Farmers were producing less than the consumer needed and the rest was being made up from released stocks.” However, in 2006 those stocks started to run out and supply and demand became extremely tight, leading to an about-turn in market direction.

“The demand for grain every year, as far back as you wish to go, has been growing,” he adds. “It’s therefore a fairly safe assumption that it will continue to rise; we will need to return a record crop every year – that should be taken as a necessary. But don’t assume that the price will go up accordingly, as historically we have always been able to raise output as needed.”

However, circumstances are becoming increasingly unpredictable in terms of weather, economics, and outside investors in grain markets. “Price is not always about supply and demand,” says Mr Redman.

“For example, London wheat futures tend to become disconnected with the fundamentals in May. There’s not a lot of old crop grain left, and attention is turning to new crop – trading becomes a lot more technical, and, as a result, more volatile.”

So uncertainty – and therefore potentially large short-term price swings – is here to stay. But the long-term outlook remains relatively bright, he adds.

“I would be confident, as a grain producer, in prices for the forthcoming 10 years. But it’s not just the headline price that matters – costs are rising too, so you need to budget carefully and ensure there is a margin left at the end.”