Estimated breeding values: How to use them when buying bulls

©Tim Scrivener

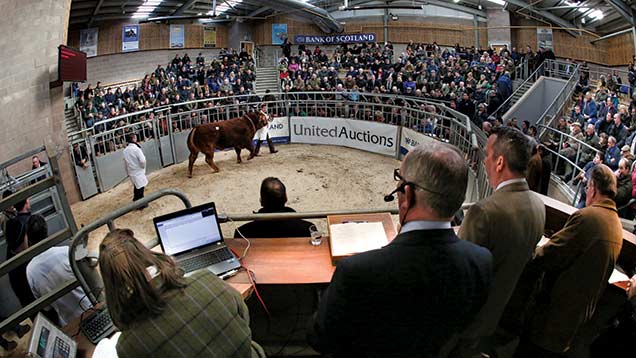

©Tim Scrivener Following on from the debate last week about showing holding back genetic progress, Gavin Hill SAC Consulting beef specialist looks at how to use estimated breeding values (EBVs).

EBVs are another tool to use when purchasing bulls, but both our eye and EBV figures must be used together. Many buyers arriving at the sales do a visual check of the bulls for the correct characteristics.

See also: Top tips when buying a bull

Only then do they look at the EBVs of preferred animals to make further selection and end up with a list of bulls that tick the boxes for both visual and genetic attributes.

Others get the catalogues well in advance of the sales and put a mark against those bulls that have the required genetics. But, rightly, they still make sure they have the character, shape, conformation, fertility, legs and feet required.

EBVs are not responsible for these crucial parts – or how the bull was reared or if he was overfed. EBVs help the decision process. They do not dictate it.

Calving ease

Often the main area that creates debate is the calving ease figure describing how easily the bull’s calves should be born. Yes, some bulls have poor ratings for calving ease; the information is there as a warning the bull could cause you severe problems when cows are not managed correctly.

At calving time, how easily the cows will calf is due to approximately 75% management and 25% genetics. We often hear of the bull that was rated as a poor calver, but he never gave any problems.

That can be correct, but it is down to choosing the right cows and managing them correctly. That is why we also hear of farmers sharing a bull where one comments on no calving issues and another has difficulties.

Many leading commercial buyers will often take home bulls poorly rated on calving ease, but because they know what cows it will be going to they can manage them accordingly.

They will say, “this type of bull never goes near my autumn herd”. Such herds are regularly in very fit condition on farm and not easy to manage through late summer so the risk of putting in that type of bull is too high.

Conversely buyers can take home a bull reasonably well rated for calving, but then they have problems because they have not gone to the right females and are not in the ideal condition for calving.

Breed differences

Farmers continually remark that they are having to switch breeds as they have had too many problems with their existing one. However, the biggest differences are often within the breeds rather than between them.

The genetics of some breeds known for their easy calving have moved on, making certain breeding lines as difficult to calve as many of the continental breeds.

Commercial buyers want to be able to make an informed choice and get the heads-up on any problems that could lie ahead.

EBV accuracy

Another criticism of EBV figures is that they are not that reliable as there is limited data on that family.

Accordingly, an “accuracy” score – determined by the number of records available on the animal and its close relatives in any herd – is shown as a percentage alongside the EBV figure in the catalogues. The more information, the higher the accuracy.

Buyers, who do not want to purchase bulls if there is a risk that their figures could alter dramatically, look for accuracy above 70% to indicate that EBVs should remain fairly static.

Below this figure the risk of change is too great for most. However, as recording improves the accuracy figures will continue to get higher and more reliable.

Growth and carcass traits have been recorded for many breeds for some time so there is plenty of information in the system. But some traits only have records covering a short period, and this is where confusion can arise.

The maternal figures, for which less information is available, will often only have about 40-50% accuracy. This makes it important, when purchasing, to ensure the growth and carcass figures are over 70%.

Some also claim that inaccurate or wrong data is being entered by pedigree breeders to improve their figures. Fortunately, breed societies are usually able to eliminate data that is found to be inaccurate as, with so much information now available on families, the system can recognise and flag inconsistencies.

However, if these bulls are sold with incorrect records and do not perform as expected, buyers will react with their feet, making any short-term gain a long-term disaster for the breeders.