Mastitis: DNA breakthrough

Mastitis testing techniques and pre- and post-milking teat disinfection were just some of the topics up for discussion at the recent British Mastitis Conference at Worcester Rugby Club. Aly Balsom reports

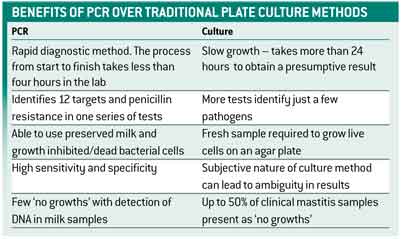

Using PCR testing to determine the cause of mastitis infection could boost producer confidence in test results compared with traditional bacterial culture analysis, according to National Milk Record’s business development manager Hannah Pearse.

“Results from cultures have often been frustrating for farmers because of the high level of ‘no growths’. However, PCR analysis is estimated to provide a bacteriological diagnosis for almost half of cases where conventional culture results are negative,” she told the conference.

PCR or Polymerase Chain Reaction is a molecular genetic technique which identifies short sequences of DNA in a sample, where as traditional bacterial culture methods involves growing bacteria on an agar plate.

|

|---|

The use of PCR technology for mastitis detection proves a valuable tool in implementing key areas of the five-point plan, she said.

“When using PCR, producers and vets can accurately identify problem cows and specific pathogens responsible for mastitis, allowing a more targeted approach to treatment.

“Excessive use of antimicrobials is a concern to the industry and consumers, but PCR has the potential to significantly improve the efficacy of such drugs.”

PCR also allows producers and advisers to adopt a more holistic approach to mastitis management by building up a wider picture of all pathogens present.

“Culture methods identify the most common pathogen found in milk samples, but often overlook issues that may be lurking on farm,” she explained.

By taking into account all pathogens identified via PCR analysis, be they causative of contaminant, it is possible to build up a better understanding of the risks to which the herd is exposed.

Ms Pearse recognised there was still a lot to learn about using such a new technology, but believed PCR offered a genuine alternative to bacterial cultures, in fact NMR converted fully to PCR analysis in February this year.

However, in response to Ms Pearse’s presentation, Nottingham University’s Martin Green, raised concerns over interpretation of PCR results.

“Just because PCR analysis identifies a pathogen does not mean it is the cause of the problem and as a result it is possible to do harm as well as good by making the wrong decisions.

“PCR needs a lot more work and we are duty bound to look further into this subject.”

Teat disinfection choice crucial

Producers need to sort fact from fiction to make the correct buying decision when it comes to pre- and post-milking teat disinfection products, said Alison Clark, farm service manager for GEAf Farm Technologies.

“As identified by the five-point plan, teat disinfection plays a significant role in reducing mastitis levels, but producers need to be able to make an informed choice to truly benefit herd health and milk quality.”

And knowing a product is registered with the relevant authority is crucial in knowing a product is safe an effective. “A VM number will be present on the side of the drum when a product has been registered with the VMD – this is required when manufacturers are making medicinal claims,” she said.

When thinking about disinfectant levels, a concentration of 0.5% (5000ppm) of biocide is ideal in iodine or chlorhexidine post-dips. Products with lower concentrations should be avoided.

“A pre-milking product must contain below 3000ppm of available iodine or chlorhexidine, but for maximum efficacy, a product containing nearer the 3000ppm figure is preferable,” she said.

Concentrations can be compromised in a combined pre and post-dip, because of the need for appropriate emollient levels (teat conditioners) in post-dips.

“Post milking products should contain emollients at 10-12% – when concentrations are too high, disinfectant efficacy could be compromised.”

But whichever disinfectant is used, all products will be put under pressure when exposed to organic matter, emphasising the need to change teat cups every milking.

Close to beating Strep uberis

The industry is one step closer to producing an effective vaccine against Streptococcus uberis, according to James Lea of Nottingham University.

“Strep uberis must survive and grow in the gut, survive in the environment and be capable of penetrating the teat – the question is, are there specific genes needed for certain functions?” he asked.

In response to this question, scientists have managed to identify sub units of Strep uberis that play a role in disease.

“When we immunise with these proteins, in the same way we use the tetanus vaccine in humans, Strep uberis would be less likely to cause disease,” he said.

And identifying strains of the bacteria that are incapable of colonising the mammary glands and causing mastitis, could also help in the control of Strep uberis.

“Would a herd shedding these strains have less levels of mastitis? And how can we use these strains as a probiotic in the future?,” he asked.