How would leaving the EU change the UK’s trade relationships?

It is Friday 24 June and the UK has voted to leave the EU. What next for trade?

There are two main elements to this: what will our trading relationship with our previous EU partners be and what about the rest of the world?

See also: Analysis: Agricultural trade in a post-Brexit world

Europe

Definitions

- Tariff – a tax on imports

- Tariff rate quota – an amount that can be imported at a reduced tariff or tariff free

- Third country – a country outside the EU

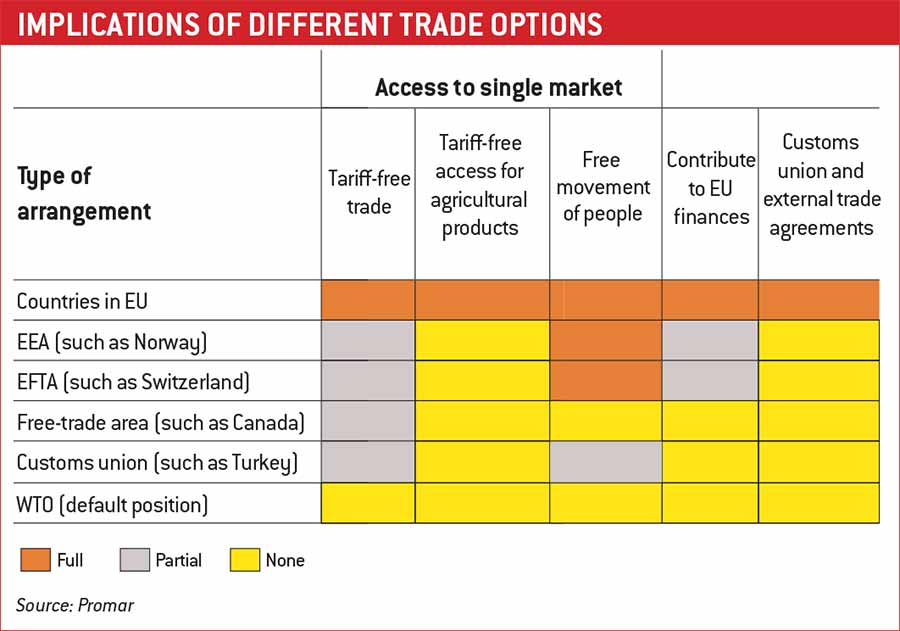

The options have been extensively analysed in numerous papers by academics, industry and government, but most of them home in on five scenarios:

1. European Economic Area – as with Norway

This gives total access to the single market, but in return the UK would be legally bound to implement EU regulations. The UK would still have to contribute to the EU budget, but would have no say in the decision-making process. Currently this model does not cover agricultural goods.

2. European free-trade agreement – as with Switzerland

Similar to the European Economic Area model, many of the same regulations would apply and the UK would still have to contribute financially. The Swiss model does not provide free-market access for agricultural goods, though it does benefit from tariff concessions under a number of separate bilateral treaties.

3. Customs union – as with Turkey

This provides preferential access for all industrial goods and processed agricultural products, but not for services or agricultural commodities. In return, the UK would have to align its food production and animal health standards to EU levels. A customs union has a common external tariff.

4. Free-trade area – as with Canada

This aims for “the highest possible degree of trade liberalisation”, with most tariffs removed or reduced. In particular, it aims to tackle non-tariff barriers to trade through regulatory convergence. It would cover agricultural trade, with some products allowed to move tariff-free up to a certain volume (tariff rate quotas).

EU common customs tariffs (average rates)

- Animal products 18%

- Dairy products 42%

- Fruit and vegetables 11%

- Cereals 15%

- Oilseeds 7%

- Sugar 25%

5. WTO default position

The UK could revert to basic World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, with tariffs on exports to and imports from the EU. These average about 12%, rising to 18% for meat and 42% for dairy. Under WTO rules, it would not be possible for the UK and EU to develop specific deals for particular agricultural products.

Predictions

So which of these models is most likely? Clearly there is something of a trade-off.

A relatively close arrangement, as applies to Norway and Switzerland, would certainly keep trade costs down, but would also mean the UK would have to replicate EU rules.

A more independent approach, such as the WTO model, would push up prices, as both sides would have to pay tariffs on traded goods, and there would be a greater cost in monitoring and checking each other’s standards.

The UK government has already poured cold water on both a Norway- and Swiss-style arrangement, stating “in both cases, the non-EU country is obliged to adopt some or all of the body of EU single market law, with no effective power to shape it”.

There is also no certainty that remaining member states would welcome the UK back into the fold. As renowned economist Allan Buckwell said: “The negotiation would be conducted in the context that UK politicians have just persuaded voters that the EU is an enormous failure.”

Emeritus professor Alan Matthews from University College Dublin believes that fear might be overstated, but he does acknowledge there is a “capacity” issue, with EU negotiators already tied up in a raft of other trade negotiations.

He suggests the most likely outcome would be a free-trade area along the lines of the Canadian model, providing generally tariff-free access. “The idea of Brexit is to get away from regulatory interference, so we can assume the UK will not want to be part of the single market,” he said.

“But a trade deal could also include tariff rate quotas, limiting access for certain sensitive products.

The French, for example, will be keen to avoid a situation where the UK increases imports of lamb from New Zealand or sugar from Brazil, which then displaces UK product into EU markets.”

Trade with non-EU countries

If the trading arrangement with former EU partners in a post-Brexit world seems complicated, the dealings that would need to be done with non-EU countries could be even trickier.

The first question, according to Prof Matthews, would be how any existing trade deals with third countries would be shared out if the UK leaves the EU. He argues that the EU would seek to retain as much of the export business as possible and “the UK would lose its market access”.

But for imports, he believes “there is a more realistic possibility that these might be divided between the UK and the EU”. Indeed, in the case of tariff rate quotas for products such as New Zealand butter or sugar from Africa, Prof Matthews argues “the EU might be only too delighted to off-load a larger-than-pro-rata share to the UK”.

The actual tariff levels set by the UK on its own would depend on who is in power following a Brexit vote. “There is something of a contradiction among those arguing for Brexit,” he says. “One group sees the EU as too protectionist and will want freer trade with the rest of the world. But others see Brexit as a means to re-establish a national identity. A strong rural England is a part of that vision, so tariffs might stay in place.”

Another issue surrounds the UK’s involvement in so-called regional trade agreements – of which there are more than 30.

If the UK leaves the EU, it will have to renegotiate these deals in their entirety, including changes to tariff rate quotas that currently help protect certain “sensitive” agricultural sectors.

There are huge uncertainties surrounding all this – not least because it has never been tried before. But, according to a recent report from the Yorkshire Agricultural Society: “If the UK is required to come to an agreement with other WTO members on appropriate tariff and subsidy levels, the agricultural sector may be somewhat exposed.”

It argues that, as part of the UK’s attempts to obtain more favourable trade terms in other sectors, it may have to concede lower tariffs and more generous market access for agriculture.

Time pressures may also put the UK in a weak bargaining position.