A poultry producer’s guide to red mite control

Red mite are a pervasive threat to almost all poultry units; they can hinder production, harbour disease and even kill birds if they get out of control.

If your poultry farm is free of red mite, you are in the minority.

New producers may get an initial window where the pest is not present on farm, but it won’t be long before control is necessary to keep it suppressed.

See also: How the latest red mite treatments perform in poultry flocks

We outline how the pest gets established, ways in which it can be monitored and methods for its control.

Why red mite are a problem for poultry farmers

The need for control is clear, according to poultry vet Sam Northing, of specialist practice Avivets.

If allowed to get out of hand, a red mite infestation can cost a farmer at least 30p a bird – a significant amount over a flock.

Red mite can feed on up to 5% of a birds’ blood over a single night, making them an obvious cause of stress and anaemia, leading to lower immunity and eventually higher mortality.

The effects of red mite

- 50,000 mites a bird is a normal, acceptable infestation level

- 150,000 mites a bird is the approximate level at which farmers will see an effect on health and production

- 50m mites a bird is a severe infestation that will cause mortality

- Severe problems can cause 10-12% reduced egg production

That stress will often also lead to unwanted behaviours such as aggression, feather pecking or cannibalism.

Hens will often eat more as well, which reduces feed conversion rates.

And while the mite’s blood-sucking tendencies are the most obvious issue, there is increasing evidence that mites act as a vector for diseases such as salmonella, E coli or mycoplasmas.

Protecting farmworkers is also a vital health and safety consideration, as red mite can be an irritant to humans.

It is thought that the move to cage-free systems is contributing to an increase in the pest, but the reason for outbreaks is multifactorial – so control must take a broad approach as well.

How to monitor the pest on your farm

The first stage is evaluating the extent to which an individual shed has a problem, says Mr Northing.

He will usually assess red mite at a farm’s annual service plan visit, or when taking on a new client.

A straightforward way to look for the disease is with a visual inspection of all the cracks and crevices in which the pest might be present.

A good tip is to dislodge the clips of feed tracks, where mite will often hide during the day.

Nest boxes are typical habitats, but can be hard to get to for farmers – at least while birds are present.

Eggs with blood spots also indicate a problem. A more thorough way to monitor sheds is with a formal testing regime.

A popular tool for this is the Avivet trapping system, often supplied in the UK by MSD.

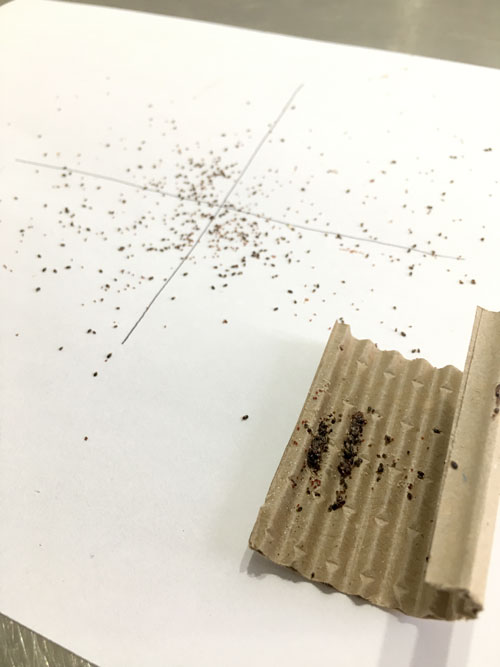

Avivet red mite trapping system

It involves placing small cardboard-contaning tubes around shed, usually under perches.

After 48 hours, the cardboard is collected and mite populations can be evaluated using extremely sensitive scales.

An assessment can also be made by counting clusters of the pest from the traps.

The results of this will give an idea of the severity of an infestation, with the results rated green for low, amber for medium-level incursions, or red for critical, where immediate treatment is necessary.

Scales to weigh the collected red mites

Trapping in this fashion will offer farmers an idea of where in a shed red mite infestations are highest.

A first treatment may be a spot-spray of those areas to try to suppress levels.

Another advantage of testing is quantifying how bad the problem is, and how well a given treatment has suppressed numbers.

Mr Northing recommends monthly tests to understand population fluctuations.

Ways to control red mite

Turnaround and placement

Keeping on top of red mite infestations begins at turnaround, according to Mr Northing.

“The first key point is to use a detergent that will dislodge any mites, eggs and larvae left behind. Wash first, allow everything to dry thoroughly, then disinfect to kill and allow that to dry, as well.”

Ideally, choose a product with a foaming agent that clings to structures and penetrates cracks and crevices.

But the most important thing is making sure cleaning is thorough, and to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Before birds arrive, there is more freedom to try insecticide-based treatments to suppress populations of red mite.

It’s worth monitoring or even treating birds in the first weeks after placement, before an infestation is allowed to get out of hand.

Biosecurity on unit

Keeping up high biosecurity levels will also help prevent the pest from becoming established; controlled perimeter fences and a single access point to farms are a good starting point.

Limiting visitors – in particular, those that have been on other poultry farms – is also an important step.

Provide people with a change of clothes and an effective foot dip if possible; farms are increasingly offering shower-on facilities, as well.

Maintaining fans and other ventilation, and generally discouraging wild birds from the farm perimeter, will also play a part in preventing the spread of red mite to farms.

And it’s important to remember that it is not just the bird area in which mites can survive – replacing things such as brushes regularly and cleaning anterooms, egg belts and other equipment can all play a part.

Once birds are in, it’s worth considering products such as diatomaceous earth in the litter, which can suppress numbers, or natural water additives that are thought to make hens’ blood less palatable.

Parasiticide

The only licenced veterinary treatment currently available while birds are in lay is MSD’s Exzolt, according to Mr Northing.

It can be prescribed by vets as part of a treatment plan.

The dose is calculated by bodyweight and administered via drinking water, and two treatments are required, seven days apart.

It is a targeted treatment that has a zero day withdrawal period and, to date, remains the most effective way to suppress a mite population while hens are placed on a farm.

The red mite explained

Red mite live alongside many types of birds, but it is the concentration of hens or broiler breeders on a farm that allows their numbers to grow to the extent that they become a problem – even backyard flocks can develop red mite issues.

They can be introduced to a farm along with incoming pullets, on visitors or be carried by wildlife – biosecurity can help.

However, there is no way to prevent their incursion entirely.

The bug begins as an egg, and in this form can be very difficult to eliminate from farms.

They tend to reside in hard-to-reach spots and can sit in stasis for many months before being activated by the presence of hens’ body warmth.

From there, depending on the temperature, it is just four to seven days before the hatched mite will be feeding, and in another three to four days, females begin to lay eggs – up to 300 a female over her lifecycle.

What treatments are available?

With the exception of Exzolt, there are no products licensed as veterinary medicines for the treatment of red mite while birds are in lay.

But a range of substances are available to farmers, with several different modes of action, and it is worth trying a mixture of control methods to get the best results.

Diatomaceous Earth is suitable when birds are in sheds, and acts by scratching through and absorbing the waxy, oily coating that protects mites’ exoskeletons, leading to dehydration.

Harmonix, from Bayer, and Dergall are both sprays that work by immobilising mites or blocking their spiracles, through which they breathe, potentially suppressing populations.

Supplements are available, such as Hensupp+ and Alphamites DW that are pitched at making birds’ blood less palatable to red mite.

And it is possible to buy natural predators to red mite, such as the Andolis mite, which attack and eat chicken red mite

Exzolt, from MSD, is considered one of the most effective treatments for red mite.

Administered through drinking water, it kills mite that feed on hens while the drug is present in hens’ blood.

A vaccine could be proven to be theoretically possible, but to date nothing has been developed that is commercially available.