Herbicide resistance in the spotlight

Pesticide sales globally topped $40.5b (£25.18b) in 2008, and of those sales, 47% were generated from herbicides. Here in Great Britain the 2010 DEFRA pesticide usage survey revealed that although fungicides dominate the crop protection market, herbicides assume a 32% market share.

This highlights the importance both globally and domestically of herbicide products for maintaining crop yields, so it is quite alarming that herbicide resistance to certain herbicidal modes of action is now becoming so widespread.

So what is herbicide resistance? It can be defined as: “the inherited ability of a weed to survive a rate of herbicide that would normally kill it”.

It occurs in two ways. Enhanced metabolism resistance (EMR), the most common form in the UK, is when the weed develops the ability to detoxify itself of the herbicide.

Target site resistance (TSR) is when a mutation blocks the site specifically targeted by the herbicide’s mode of action and results in complete resistance at that particular site, but the weed remains susceptible to other modes of action.

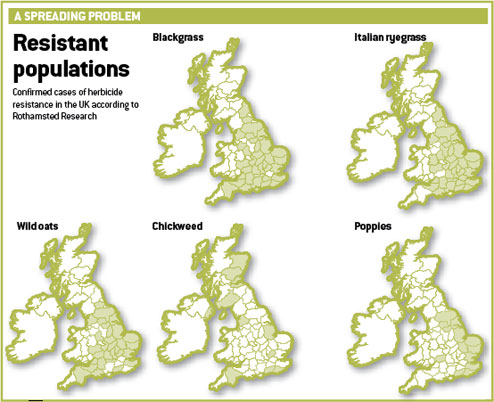

Herbicide resistance now occurs so widely in the UK it is impractical to record individual cases.

Both grassweeds, and to a lesser extent broad-leaved weeds, are becoming increasingly difficult to control with the available chemistry where resistance is found.

The highest risk modes of action include ALS (acetolactase-synthase) inhibitors and ACCase (acetyl Co-A carboxylase) inhibitors, with weed populations having developed both target site and enhanced metabolism resistance to both sets of chemistry.

Worryingly, ALS inhibitors (such as Atlantis) account for 32% of grassweed herbicide use in the UK and ACCase inhibitors such as the “fops”, “dims” and “dens” 18%, which has led to the vast rise in the biggest weed threat facing growers – resistant blackgrass.

“Of the 20,000 farms known to use herbicides to control blackgrass, we have estimated that at least 80% of those will have some level of resistance to at least one herbicide,” says Richard Hull of Rothamsted Research.

“Perhaps the second most common herbicide-resistant weed in the UK is Italian ryegrass, but there has never been any evidence of ALS target site resistance (TSR) in that.

Most populations will have some enhanced metabolism resistance (EMR) though, and ryegrass populations do show high levels of TSR to ACCase chemistry,” he explains.

Complaints about problem wild oat populations have largely died out, continues Mr Hull, as the Atlantis and Broadway products have been so effective.

“They are also a self-pollinating species, which doesn’t allow the spread of the resistance genetics.

“The out-crossing capabilities of blackgrass is one of the drivers behind the rapid spread and escalation of resistance across the UK,” he adds.

Broad-leaved weeds are less of an issue, but there is ALS TSR in chickweed, predominantly in Scotland where there is a trend towards spring cropping and subsequent reliance on sulfonylurea herbicides. “It seems to be TSR or nothing in broad-leaved weeds from what we can see at the moment,” says Mr Hull.

“There are no shades of grey like we see in grassweed populations.

“ALS resistance in poppy populations tends to occur down the east coast of the UK, (see map, above) which at present we don’t have an explanation for and from sampling we have only found four or five populations of ALS-resistant mayweed,” he notes.

Post-emergence problems

When Bayer CropScience introduced ALS inhibitor Atlantis to the UK market in 2003, the product was so effective at controlling blackgrass in winter wheat that its use was soon almost universal across the wheat producing area.

It is not surprising then that a high-resistance risk product such as Atlantis has taken less than a decade to lose efficacy in some blackgrass populations.

“There is no doubt that there has been some irresponsible use of the product, which has made the issue of resistance inevitable,” says Chris Cooksley, combinable herbicides campaign manager at Bayer CropScience.

“However, Atlantis resistance is not endemic and it is still effective in many areas.

“We would hope that stewardship advice to slow the build up of resistance will have been taken on board,” adds Mr Cooksley.

The difficulty that growers face where resistance to Atlantis has been found is the lack of alternatives.

“Cross-resistance has developed, meaning that the resistant populations are likely to be resistant to chemistry from the same group,” continues Mr Cooksley.

“Broadway products or Unite will very often be as ineffective as Atlantis where ALS TSR is present, as they are also ALS inhibitors, so they are certainly not a solution. We need to look for different modes of action if we are to sustain post-emergence blackgrass control,” he says.

This is an opinion echoed by Dow AgroSciences’ principal biologist for cereal herbicides and insecticides, Dilwyn Harris, who points out a new herbicidal mode of action with activity on blackgrass is the Holy Grail. “Where Atlantis has broken down to TSR, pyroxulam products will not be effective either, unfortunately, so there is no alternative.

“We are actively commited to research and development to find a new mode of action, but until then, where resistance is present in blackgrass, we will have to use all the tools available,” he adds.

Active ingredients

- Active ingredients

- Aramo – tepraloxydim

- Atlantis – iodosulfuron + mesosulfuro

- Avadex – tri-allate

- Broadway Star – florasulam + pyroxsulam

- Broadway Sunrise – pendimethalin + pyroxsulam

- Crawler – carbetamide

- Hurricane – diflufenican

- Unite – flupyrsulfuron + pyroxsulam

“Using sequences of residuals is the most important chemical aspect, as this ensures that there is as little blackgrass as possible for the post-emergence herbicides to take out.

“Where the post-emergence ALS inhibitors are used, apply them early on small plants to give them the best possible chance of working,” says Mr Harris.

Risk with residuals?

With limited and increasingly less effective post-emergence products, there is an increasing reliance on the “stacking” of pre- or peri-emergence residuals for weed control, in particular blackgrass. It asks: are they also at risk of resistance build-up?

“Resistance is increasing in post-emergence herbicides, so we are stacking more and more residual herbicides as our main method of blackgrass control. For example, in 2010 flufenacet applications in wheat had over taken Atlantis, demonstrating our increased reliance on this chemistry,” says Mr Hull.

There are levels of EMR resistance to all pre-emergence herbicides, including tri-allate and prosulfocarb, but of concern to growers and advisors will be the news that Mr Hull has been able to select for resistance to flufenacet and pendimethalin under controlled conditions at Rothamsted Research, showing a decline in efficacy of around 5% per year due to the build up of EMR.

“That is the worst news, but comparisons with what is actually happening out in the field are not as pessimistic,” explains Mr Hull.

He points out that although it is very hard to evaluate the performance of pre-emergence herbicides in the field due to variations in conditions and masking from other actives used in control programmes, data released from chemical manufacturers back up his own research.

“It is telling us that these actives are only losing efficacy at a rate of less than 2% per year. However, this average decline may not solely be attributed to an increase in resistance, as there were fluctuations in control linked to autumn rainfall. The increasing reliance on pre-emergence sprays is sustainable, it seems, in the short to medium-term, but probably not in the long term,” says Mr Hull.

The less specific mode of action of flufenacet makes it lower risk for resistance and consequently should be the core of most pre-emergence treatments, but Mr Cooksley reminds us that we will be in much trouble without it. “Where would we go?” he asks.

“There is certainly a decline in efficacy, but we would hope that it bottoms out eventually and will always give a reasonable level of control. Stacking will help maintain high levels of control for longer and growers should make application an art form,” says Mr Cooksley.

| Scale of resistance | |

|---|---|

| Resistance | Expected control (%) |

| S (susceptible) | 90-100 |

| R | 80-90 |

| RR | 40-80 |

| RRR | 0-40 |

Broad-leaved weeds are much less of an issue when considering herbicide resistant populations, but in Scotland and Northern Ireland where there is a higher proportion of spring crops – in particular spring barley – ALS target site resistance has developed in populations of chickweed.

The problem stems from the overuse of sulfonylurea herbicides such as metsulfuron and thifensulfuron without a partner that works with a different mode of action.

Mark Ballingall, senior weeds consultant at the SRUC, believes that after banging the drum for resistance stewardship for many years, the penny has now dropped.

“Cheap Chinese manganese that was flooding the market a number of years ago didn’t mix with Hurricane, so a sulfonylurea was applied with the trace element and although growers intended to apply the Hurricane, it was widely forgotten leaving the sulfonylurea to stand alone,” he says.

Summary

ALS target site resistance rising in chickweed

More work needed on mayweed

Mix sulfonylureas with hormones

Growers urged to send suspicious samples for testing

The last survey conducted in Scotland found 40 confirmed cases of TSR resistance to ALS inhibitors, which includes all sulfonylurea herbicides, however Mr Ballingall believes the problem is far more widespread than figures suggest.

“It’s not endemic yet, though. There is a very simple solution to the problem and growers should be mixing a hormone herbicide such as fluroxypyr or a good dose of dicamba + mecoprop-P with their sulfonylurea to give a different mode of action,” he explains.

It has been suggested that ALS resistance in mayweed has also been increasing, but Mr Ballingall remains sceptical.

“At present we are working on mayweed, but we only have anecdotal evidence so we need more samples where resistance is suspected to get a better idea as to the extent of the problem,” he notes.

Mr Ballingall also notes that when samples have been received they have often been in poor condition and provided uncertain results in glasshouse tests.

“The sampling needs to be done properly and growers can get advice on how to carry out sampling on the Weed Resistance Action Group (WRAG) website.”

Double death delayed drilling

When you have been growing continuous wheat on parts of your farm for approaching 70 years, it wouldn’t be a surprise to many that blackgrass populations found across the cropped area have developed herbicide resistance to ACCase and ALS herbicides, among others.

Farming 1,000ha around Peldon Hall, Peldon, Essex, John Sawdon now has around 800ha in continuous wheat and resistance was first confirmed in 1984 to old herbicide stalwart’s isoproturon, chlorotoluron and diclofop.

“The blackgrass occurs in patches right the way across the farm and we started to address the problem immediately when it was confirmed. It is mainly enhanced metabolism resistance, as it is resistant to certain chemicals it hasn’t had a whiff of before,” says Mr Sawdon.

“It has got steadily worse and no one has worked out why our populations have developed such a fierce resistance and how. We have had coachloads of manufacturers and experts from all over the world coming for seed samples in June.”

Ploughing was the first strategy that Mr Sawdon implemented to try and counter the problem, however, the 60% London clay is pretty unforgiving when conditions aren’t perfect. “We had contractors almost leaving in tears trying to make a good job of it.

“Ploughing can certainly help if you can get a good inversion, but it is not possible on our land in certain years, with ‘horses heads’ about the best you can hope for.”

Peldon Hall Farm, Peldon, Essex

Size 1,000ha (800ha cropped)

Soil type Heavy London clay

Cropping Continuous wheat (milling)

Cultivations Min-till

The Väderstad min-till system, which is employed at Peldon Hall, was adopted in 2004 and since then Mr Sawdon has seen the patches of blackgrass remain fairly stable and he believes keeping the seed near to the surface is an advantage.

“The min-till system will conserve moisture in that surface layer, allowing us to get a good chit of the blackgrass to spray off with a glyphosate, even when the autumn is dry. We have been delaying drilling as much as possible to get as much out of crop control as possible,” he says.

The delayed drilling has been key to his strategy against the resistant blackgrass and investing in a Challenger with an 8m Väderstad drill allows a high work rate to cover the acreage as quickly as possible before conditions become catchy.

The wet autumn this year has troubled the Väderstad drill, forcing Mr Sawdon to buy a Maschio Primavera tine drill to be able to drill in the wet conditions. “We are pleased with the results and only have 100ha left to do,” he points out.

“We are really upping the ante on the resistant blackgrass. We won’t drill now until the ground has had two glyphosate applications, even if it means drilling in December. Hence, double death delayed drilling. We will hope to see a positive result come the spring.

“I won’t change the cropping system [continuous wheat], so this is the best way forward,” adds Mr Sawdon. “You may be losing yield gradually the later you drill, but it’s better than drilling early and losing 2t/ha from blackgrass infestation.”

Chemical strategy is no different to the current industry standard, with residuals such as prosulfocarb and pendimethalin built around the core active, flufenacet. “We have just increased sprayer capacity, with a 48m boom and 8,700-litre tank, to ensure that we get our timings correct on what can be tricky land. Minimal downtime is key,” says Mr Sawdon.

“Atlantis still has a place, and you would be a brave man to take it out even though I believe it doesn’t give us much. It’s difficult to assess the control level it is giving us, but even if it’s 5-10% it’s better than nothing.

“Looking to the future, I would hope we could have the technology to accurately spray out patches, but so far it has been slow to develop,” he concludes.

Short-term pain for long-term gain

Farm manager at RH Topham and Sons, Ian Lutey, is taking a flexible and long-term approach to controlling widespread resistant blackgrass across his cropped area.

Since taking the reins at the farm five years ago, extensive resistance testing of blackgrass populations has highlighted the challenge that he faces. “It isn’t just going to go away,” he says. “We have RR and RRR ALS and ACCase resistance right across the board now and we had to make some tough decisions to find a strategy that works.”

Minimising seed return has been key, explains Mr Lutey. And despite many of the advised resistant blackgrass management methods involving a short-term economic penalty, he believes it must be accepted to implement a sustainable grassweed control strategy.

“We must take some short-term pain for the long-term gain. I decided to review cultivation strategy, rotation, drilling date, seed rate and also the chemical strategy, as we are only achieving 40-50% control in our wheats with Atlantis.”

Mr Lutey took the decision to move to rotational ploughing immediately on his arrival, and currently soils are turned over one year in five. “Previously it was all min-till and introducing the plough has certainly not cured the problem, but it has given us a big head-start.”

The plough is used to establish second wheats and spring beans, with the spring cropping the next key factor in cleaning up resistant blackgrass.

“Spring beans have been a regular here for a long time, but control options in the crop are becoming increasingly limited, which is why I decided to introduce spring barley. It also gives a better economic return and is more competitive than the spring wheat,” says Mr Lutey.

There is no specific rotation, with cropping plans formulated on a field-by-field basis dependent on blackgrass levels and its susceptibility to the chemistry available. “Where resistant blackgrass is bad, we replace the second wheat with a spring barley or substitute the oilseed rape for spring beans.

RH Topham and Sons

Size 1,400ha (1,300ha cropped + ELS)

Soil type Heavy clay

Cropping Winter wheat, oilseed rape, spring beans and spring barley

Cultivations Min-till and rotational ploughing

“In some situations, where control has been poor, I have used multiple spring crops. Although returns are not so good, I felt it necessary to clean those fields up before entry into the oilseed rape, which then offers another bite at the cherry with effective chemistry before our first wheat,” says Mr Lutey.

Oilseed rape is Mr Lutey’s main focus for chemical control within the rotation as propyzamide and carbetamide remain very effective at killing blackgrass, with no known resistance. “The pre-emergence choice is a metazachlor mix and where blackgrass is bad a post-emergence Aramo will be applied to give some additional kick-back.

“I’m a firm believer in getting the propyzamide applications on as early as conditions will allow and carbetamide will be used on the odd patch. We were going to try the new Crawler sequence this year, but conditions have not let us get around to it,” he points out.

Direct drilling has brought another dimension to Mr Lutey’s control strategy in oilseed rape, with propyzamide applications known to be more reliable where soils have not been disturbed. “It also means there is less blackgrass coming up from depth, which you get with a subsoiler, and it struggles to kill it,” he explains.

The farm’s flexibility has been demonstrated again this year, as Mr Lutey did not deem conditions right to direct drill, so he used alternative methods. “It’s a horses for courses situation,” he adds.

Residual focus

When returning to the source of the resistance problem – in the winter wheat crop – the reliance on residual stacking is now strong, with a number of key actives being used to give the maximum control and reducing the workload of the Atlantis at post-emergence.

A full rate of flufenacet is the core of the programme, accompanied by diflufenican and Avadex is applied where possible. “We have now kitted ourselves out with an Avadex applicator on the rolls, but so far this year we haven’t been able to roll,” Mr Lutey says.

“Where we can’t get on with Avadex or there are high blackgrass populations, we will come back with another half rate of flufenacet. It’s about getting the balance right between crop safety and the weed control.”

The challenges that the heavy reliance on residuals brings to the table are spraying capacity and seed-bed quality, with the correct timing of application and a well consolidated seed-bed is vital to ensure maximum efficacy.

“I would rather spend money on fuel getting the right conditions for my most effective chemistry than spending money on herbicides that I know aren’t going to give me the same level of control,” adds Mr Lutey.

“We are also drilling a minimum of 300 seeds/sq m and upping the seed rate where needed to establish the most competitive crop we can,” he says.

“Variety choice is less important, in my opinion, as you have to look at your end market as well as blackgrass suppression and we are growing fairly competitive varieties anyway.”

Positive outlook

Mr Lutey is now much less concerned about his resistant blackgrass populations than when he arrived on the farm five years ago, with the varied and flexible approach paying dividends.

“With everything set against the development of new products, we have no choice, but to maximise the potential of cultural methods and the chemistry we have. Although we will never get rid of blackgrass altogether, I think we can manage the populations we have.

“People need to change their attitudes to prevent this problem escalating beyond the point of control,” he concludes.

Share your thoughts and experiences of herbicide resistance on our dedicated forum