Time to end stagnant wheat yields

A focus on cutting costs and some crops being starved of nitrogen are two factors being implicated in the stagnation of average on-farm wheat yields since the mid-1990s, according to experts.

However, a lack of progress in plant breeding or crop protection, is not thought to be part of the reason for this yield plateau, say scientists.

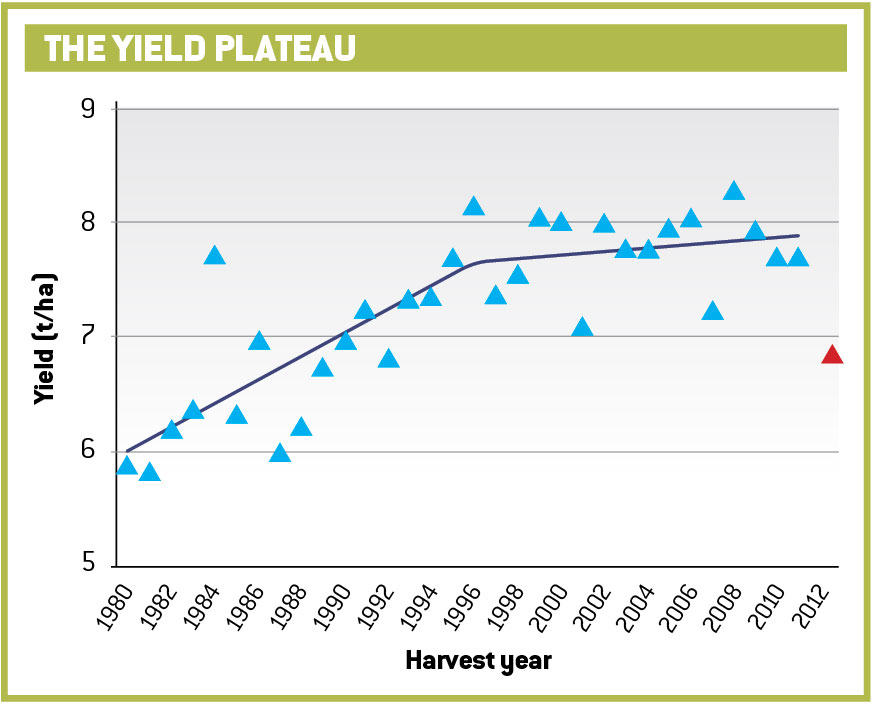

Looking at the national trends, yields increased by an average of 0.1t/ha each year from 1980 until the mid-1990s, in line with the extra tonne a decade improvement that occurred from the end of the Second World War. But since then progress has plateaued with the average increase barely reaching 0.02t/ha.

Yet it seems there is the potential to achieve 15t/ha or even 20t/ha in UK wheat crops. Britain’s champion wheat grower David Hoyles harvested a 14.3t/ha crop in southern Lincolnshire in 2011.

In addition, there’s a sizable gap between the average yields achieved on farm (about 8t/ha) and in Recommended List plot trials (control average of 10.2 t/ha in 2012) where robust inputs and careful site selection aim to minimise lost potential.

The first step in breaking the barrier is to identify the causes for the stagnating yields and that’s why DEFRA and the HGCA funded a desk study last year, with experts examining data for trends and possible constraints.

The study looked at many different sources of data such as national statistics on fertiliser and agrochemical use, crop trials including the HGCA Recommended List sites, disease and crop survey information from CropMonitor and Farm Business Survey figures including trends on input spend, plus the researchers interviewed case study farmers.

“Yields are a function of variety potential, weather and agronomy; it is a complex relationship,” says Stuart Knight, director of crops and agronomy at NIAB TAG, who headed the study.

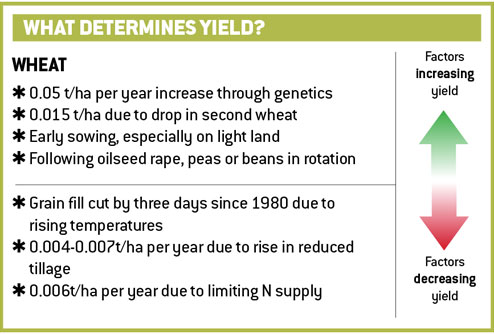

About half of the extra tonne a decade (achieved from the mid-1940s through to the mid-1990s) was coming from variety improvements and the other half was from improved agronomy and other positive year effects. This included technical advances in fertiliser use, crop protection and cultivation methods.

Since the mid-1990s, genetic potential has advanced at a similar rate, but the national yield has stagnated and something is holding back overall progress. “One reason could be that growers haven’t been benefiting from this genetic improvement, but all the evidence points to a pretty good uptake of new varieties, therefore this doesn’t explain the plateau.”

Changing climate

“Climate and weather is another factor, and yes there has been an impact.” But Mr Knight adds that a lack of good or consistent data makes it difficult to quantify some of the yield effects and much of the information is very disjointed.

“For example, there was one set of national data on fertiliser use and another for yields. What is needed is data at the individual farm level rather than having to use averages from different data sets.”

Last year clearly demonstrated the impact that weather can have. “We know that sunshine at grain fill has an effect and explains some of the annual variation, but there is no real trend over time and this doesn’t fully explain the yield plateau.”

In recent years there has been a tendency towards more extremely wet or very dry conditions.

During the 2000s, there is evidence from RL trials that dry springs and summers have dented improvement in yields in eastern England and on light soils or for later sown crops. In the North and West, and on heavier soils or earlier sown crops, yield trends over the same period fared better.

“Then came 2012, a really wet season, which was one of the best recent years on light soils or for later drilled crops in the east, while crops further north and west or on heavy soils suffered,” he says.

Nutrition

Clearly nitrogen supply has become more limiting and average nitrogen fertiliser use hasn’t gone up despite the fact modern varieties have a higher nitrogen requirement than those in the 1980s. This appears to be reflected in the reduced nitrogen contents from the HGCA grain- quality surveys.

“All the evidence points to nitrogen limiting the yield of at least some crops, but it does not explain the entire yield gap, just a small part of it,” says Mr Knight.

Looking at other nutrients, he says there is no evidence they are limiting yield; potash and phosphate could be a future problem as soil indices fall.

“For sulphur there was a blip in the late-1990s, but this has been pretty much ironed out in the past 10 years through sulphur fertiliser use, so does not explain the plateau.”

Agchem use

The past 10 or so years have seen a rise in the use of fungicides and herbicides, as growers have responded to the challenge of maintaining disease and weed control despite increased pressure and resistance. “There is no evidence growers have taken their foot off the crop protection pedal to cause the yield plateau.”

One key challenge is resistant blackgrass, but again there is little survey data to link this with yields, he says. “One recommendation [from the study] was for improved monitoring of weed populations. We already monitor for diseases in national surveys, but not weeds.”

The biggest effect of blackgrass is often how it impacts other aspects of crop management, for example growers may not be able to benefit from earlier drilling. “Battling blackgrass may mean they are not able to adopt the best practices for yield.”

Cultivations and soil

One debate has been the impact of the switch from ploughing to min-till cultivations. “From the limited published data, responses have ranged from zero up to 4% yield loss. Overall, the effect on national yield is small and does not explain a significant amount of the plateau.

“However, the biggest concern hinted at by the ongoing NIAB TAG Star Project is the transition period [when switching from ploughing to min-till] when yields can dip. Managing this transition period is key in maintaining yields.”

Staying with soil, there has also been talk of deep soil compaction getting worse over the past two decades. “But we don’t have the data to quantify this and there is a real knowledge gap on the extent and severity of the problem,” says Mr Knight.

Changes in rotations could also be holding back wheat yields and one recent trend has been the move towards oilseed rape being the key break crop at the expense of pulses. But evidence for this in the UK is limited as there are very few recent rotational studies.

The declining investment in drainage could also explain some of the loss in yield, as highlighted in a wet season such as 2012, believes Mr Knight. Waterlogging at key times of the year, such as during grain fill, can have a significant impact on yield potential.

Emphasis on yields

Chairman of the NFU combinable crops board Andrew Watts puts some of the plateau down to a change in emphasis. “Somehow we have got to get back to seeing the increments as seen in the 1970s and 1980s.

Back in the mid-1970s, there was rapid expansion and there were strong signals to push for production. Added to this was the new advice and big technological advances.

“I recall when Tilt (propiconazole) was first launched, it was a revolution. And there were no restrictions on nitrogen use, with the RB209 being largely a measure of the economic optimum.”

Then came the grain mountains in the 1980s and prices fell below the three figure mark in the 1990s. Subsequently, there was a shift in emphasis to cost of production with no real incentive for increasing production.

But now as wheat prices edge nearer £200/t, Mr Watts believes there is an opportunity to be pushing yields again. “The question is how much is the UK and Europe going to help meet this extra global demand for food. Are we being responsible if we don’t realise the potential in the UK.

“The fact we are now talking about it is good news and we could be seeing a reawakening,” he says.

Mr Knight agrees the main benefit of the report is the debate. “People are talking about it and are putting forward their theories for the plateau. It is really healthy seeing the debate and getting farmers thinking about raising yields.”

But Mr Knight warns there is no one solution to the yield plateau, but a combination of factors.

However. Mr Watts fears the growing challenge of controlling grassweeds and the potential loss of triazoles. “The loss of triazoles as part of the EU endocrine disrupter review is a new barrier for raising yields and is a real concern.”

The latest initiative, launched this month by the Yield Enhancement Network (YEN), is an on-farm competition for the highest wheat yield in 2013.

YEN is a group of farming organisations looking to develop a knowledge exchange programme and work with farmers to improve yields.

ADAS principal scientist Roger Sylvester-Bradley believes it will foster and energise innovation in the arable industry. “We need to understand how bigger yields can be produced.”

Therefore, the group launched a competition earlier this month inviting growers to produce the highest yield, or get as close to the potential yield as predicted by an ADAS model using the farmer’s circumstances, such as soil type and rainfall.

“Obviously there’s a lot of potential to improve crop productivity, but while crop prices have been low, growers have been more preoccupied with reducing their costs. The network’s objective is to re-energise interest in realising high yields.

“Somehow we have got to get the culture back in farming that it is worth innovating to increase yields,” says Prof Sylvester-Bradley .

YEN members include ADAS, BASF, Bayer CropScience, Frontier, Hutchinsons, Syngenta and Yara.

Any grower aspiring to get close to the maximum potential yield of their land can join in by accessing www.yen.adas.co.uk or by contacting the competition’s farming industry partners.

Gold, silver and bronze awards will be given for growers with the highest absolute yield and also the highest percentage of potential yields.

Similar prizes will also be awarded for trial plots, all of which will be awarded at an autumn conference on 13 November.

The cost of entry will be £250 for which growers will get an analysis and report on their yield attempt, including an assessment of the yield potential at their site.

Scientists at Rothamsted Research see improving the photosynthesis of wheat as the key part in achieving the target of 20t/ha within 20 years in the 20:20 wheat project.

They say the efficiency of photosynthesis in maize is twice that of wheat’s 3%, suggesting this is a key bottleneck to increasing wheat productivity.

Martin Parry and Malcolm Hawkesford are leading the work and part of that is to raise the percentage of intercepted radiation to be used for photosynthesis.

“Photosynthetic capacity and efficiency are important bottlenecks to raising wheat productivity and increasing these will, therefore, underpin our approach to increasing yield potential,” says Prof Parry.

Maximising yield potential is only the first of four targeted areas within the project.

The second area is protecting the yield potential with the focus on three key yield-sapping diseases: take-all, septoria and fusarium head blight.

The third area under focus is soils to improve rooting, making a canopy and utilise nitrogen usage as the yield responds tend to flatten out above applications of 200kg/ha.

Finally, mathematical modelling is being carried out to determine the best farming system for growing high yielding crops.

The HGCA/DEFRA-funded report highlighted several key factors that are responsible for the current wheat yield plateau, so what is being done to break the barrier?

The starting point is with the HGCA, which is addressing the key findings within in its ongoing research programme, including the significant variability in yields over years and between regions across the UK.

Susannah Bolton, head of research and knowledge transfer at HGCA, says there is now a greater focus on understanding regional conditions, including investment in weather stations at the Recommended List (RL) trials sites.

“In addition, we are running the pilot ‘cropping systems’ sites in Cornwall and Banbury, with plans to extend to the North East and Scotland over the next two years.”

The cropping systems project will further test varieties in more extreme environments, under high disease pressure and under different agronomic conditions to assess the impact on yield and grain quality.

Another factor was climate change and increased incidence of extreme weather and drought in the East.

“Using data from the RL trials has enabled us to analyse the contribution that the severe weather in 2012 had on UK crops and compare it with previous years.

“This will help us identify the role played by disease in different regions and develop improved monitoring and forecasting systems to enable growers and advisors to respond more effectively in future.”

The HGCA has also funded work at Rothamsted using data from previous RL trials that evaluated UK winter wheat varieties for drought tolerance and water-use efficiency.

“It has provided valuable information for plant breeders that can be used to develop varieties for the future that are more drought tolerant as well as higher yielding,” she says.

Finally the deterioration in soil health and deep soil compaction is being tackled in a joint £1.85m initiative with the Potato Council, she says.

“Research is being carried out into improved soil management, including investigations in cultivations, rotations and making better use of organic amendments.”

Wheat yields are unlikely to increase significantly beyond 8t/ha unless growers apply more nitrogen, prompting one agronomist to call for changes to the N-max rule.

Many crops are being starved of this key nutrient because of the fear of falling foul of cross compliance rules by exceeding nitrogen limits, says independent crop nutrition consultant Chris Sutton.

HGCA Recommended List trial yields suggest growers should be getting around 11t/ha from modern feed wheat varieties, but since the mid-1990s the average UK yield has remained static.

Crop yield is a consequence of many factors, including climate, soil type and previous cropping. However, Mr Sutton points to the Survey of British Fertiliser Practice, which shows the average amount of nitrogen applied to feed wheat in the UK over the past 15 years has remained static at about 190kg N/ha.

“It is totally unrealistic to expect 10-11t/ha of wheat when we are barely putting enough nitrogen fertiliser on to produce 8t/ha.”

Yara’s head of agronomy Mark Tucker agrees that nitrogen could be one reason for the yield plateau, particularly when combined with the trend of falling potash and phosphate applications.

“It does raise the question, are farmers applying the optimum nitrogen rate to exploit these newer varieties? Average use is not in line with average requirement for arable cropping or even grassland,” says Mr Tucker.

Looking ahead, Mr Sutton says growers need to go back to basics and look at how much nitrogen crops actually require and where it is going to come from.

“A generally accepted figure is that 23kg of N must be taken up to produce each tonne of grain. Therefore, a 10t/ha crop has a total uptake of 230 kg N/ha.

“But the problem is that the nitrogen cycle is very leaky and difficult to predict with total accuracy,” he says.

Soils contain a huge reserve (up to 5t/ha) of mainly unavailable organic N. A small proportion becomes available to growing crops through weathering and nitrification. The DEFRA Fertiliser Manual RB209 gives guidance on how much is available though the Soil Nitrogen Supply Index.

Most growers grow wheat with an index of 1, which according to RB209 equates to about 70kg N/ha. This nitrogen is assumed to be used at 100% efficiency and so can be taken off the total 230kg/ha requirement, leaving some 160kg N/ha to be supplied by bag fertiliser, he says.

“However, this applied inorganic N is only taken up by the crop at 60% efficiency, or less if applications are poorly timed. So for the crop to take up 160kg N, we need to apply at least 260kg N/ha, much higher than the current 190kg.”

But it’s not just limiting yields of feed wheat, growers are also missing out on milling premiums by failing to hit the 13% protein target with today’s higher yielding milling varieties.

Combine data often confirms that some fields or parts of fields do yield in excess of 11t/ha or even 12t/ha. Normally this is when conditions allow greater root penetration and higher than normal mineralisation. The fact that these crops are able to access higher levels of nitrogen confirms their ability to yield, he says.

“It is just that too often we are not fertilising to their potential,” he adds.

But in most cases you can’t simply apply more nitrogen because of the rules.

“You are probably farming in a nitrate vulnerable zone and a statutory part of these regulations is the N-max calculation. For feed wheat, this uses a ‘standard’ yield of 8t/ha and imposes an application limit of 220kg N/ha averaged over your total feed wheat area.”

While it allows you to apply more N, the rules state: “If you want to adjust the N-max limit for a crop on the basis that you expect to achieve a higher than standard yield, you should have written evidence from at least two previous crops to show this is a realistic estimate of the likely crop yield.

“Here lies the problem,” says Mr Sutton. “You can’t apply more N unless you can show that you have achieved higher yields in the past, which you probably can’t do because you haven’t been able to apply more N.”

But one way round this is to carry out farm trials, even just taking half a field and applying an extra 20-30kg/ha, as long as the farm average is still within the N-max.

Then use this yield increase as evidence to use more nitrogen, which Mr Sutton has successfully done for some of his clients in East Anglia using combine data.

He believes the problem is the wording of the regulations regarding N-max and the restrictions imposed.

“There is a need to look at relaxing the restrictions so that we can take advantage of the improvements in yield potential given to us by the breeders,” says Mr Sutton.