Farming in France – how the pioneers fared

A promise of adventure and cheap loans lured young Brits across the Channel in the 1980s to begin new lives as French farmers. Three decades on, Jez Fredenburgh catches up with three couples to see if la vie Française lived up to expectations

‘It was like a summer camp all summer, every summer’

‘It was like a summer camp all summer, every summer’

What better place to start than with my parents, Jo and Roger Fredenburgh, who moved to France 30 years ago to set up the country’s first deer farm.

Neither had farmed before, but Dad had worked on an agricultural research station in Syria. “Moving to France was the only way we could farm. Land was cheaper and young farmers were being encouraged with cheap loans,” he says. Both could earn more in their research and teaching careers, but the opportunity to farm and have an adventure were bigger pulls.

Dad had the idea after hearing about Scottish farmer John Fletcher, who was pioneering UK deer farming. After visiting Mr Fletcher, they bought a mixed farm of 65ha in La Vienne, mid-west France.

“There was one cold tap, holes in the roof, no heating – and a huge manure pile outside the door,” says Mum. Within weeks 50 hinds and three stags arrived from Mr Fletcher. “Our farming neighbours were sceptical, but wonderful,” says Dad. “They were always ready to come to the rescue.”

The deer herd expanded to 350 and Dad grew sunflowers and cereals as cash crops, maize and grass silage. But making a living was hard. “Large landowners saw us as a threat,” says Dad. “They couldn’t understand we wanted to farm for meat, not host shoots. Several were MPs and lobbied against us – they made it illegal to sell venison outside hunting periods.”

To get around this, they froze meat to sell out of season, made paté and bottled stew, built a farm shop, held open days, and toured events selling “veniburgers”.

Media coverage created an interest from farmers, so Dad started importing deer fencing and rearing “start-up stock”. He became a consultant on deer and gained a reputation for darting. To make ends meet, Mum taught in schools and ran a B&B. “Financially it worked, but we hit a period of awful droughts,” says Dad. “One year we had to treat the straw with ammonia to make it edible. Local farmers were desperate, so those up north clubbed together and sent hay down. It was humbling,” he says.

The lifestyle couldn’t have been better, though. “The people were friendly, the weather great – it was a wonderful outdoor life,” says Mum. Thirty friends and family visited every summer. “It was like a summer camp all summer, every summer,” says Mum.

The decision to return to the UK in 1994 wasn’t easy. The farm needed an injection of capital, Dad was battling serious illness and Mum’s career had been on hold. But are they glad they made a go of it? “Yes!” says Mum, “it was wonderful”.

‘The dog was a smash hit on French TV’

‘The dog was a smash hit on French TV’

Tim and Chrissie Green only planned to stay five years. Three decades on, however, they’re still at Ferme de Vimer and don’t plan on leaving anytime soon. The couple became two of Farmers Weekly‘s most well-known faces after moving to central Normandy in 1983 to manage the magazine’s French farm.

The opportunity arose while Tim was managing Farmers Weekly‘s dairy farm in Dumfriesshire (the magazine ran seven farms). “My manager visited one day and said, ‘We’ve found this farm in France, what do you think?'” remembers Tim. “We didn’t really think about it – it was to go, or find another job.”

The tenancy was arranged, and Tim and Chrissie moved to start a new life with their three young children, sheepdog Tweed, and 32 dairy cows. “The only thing we really worried about was how the kids would adapt,” says Chrissie.

On arrival they found the house bare, but nestled in its own grassy valley with 70 dairy cows, some youngstock, and 130ha of arable and grassland. Only one room of the house had been lived in and rabbits kept in the loft.

“It was all daunting because of the language,” says Chrissie. Even the cows found it challenging. Tim would call and 32 – Scottish – cows would turn around, then his local cowman would call and 70 – French – cows would turn around. “Now the cows are all bilingual,” laughs Tim.

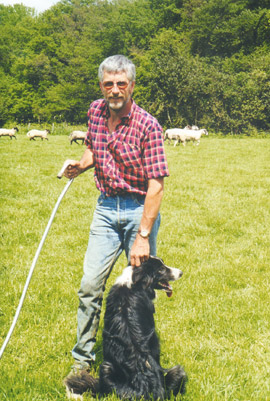

“We had four brilliant assets to help us fit in though,” he says, “our three children, and our border collie.” The girls started school within days and were bilingual within a year. Through them, and their “exceptional” landlady Madame Dufresne, the Greens made friends, and Tweed helped integration with the farming community, who were in awe of his rounding-up skills.

The following year put them (and Tweed) on the map. Media descended on Normandy for the 40th anniversary of the D-Day Landings, and become aware of the Green’s venture. BBC News, Farming Today, Women’s Hour, the Norwegian press and CNN flocked to the farm. “The dog was a smash hit with French telly!” says Tim.

Among press attention, Tim and Chrissie worked to improve the farm. To begin with, the dairy provided the majority of their income, although quotas limited them to 570,621 litres annually. To increase their income and grow their flock, Tim went on a 125-mile round-trip to buy 12 sheep, but on arrival found five had been stolen. “I was quite glad – they were the worst sheep I’d seen!” he says.

He wasn’t impressed with the French sheep industry. “It was cobblers,” he says. “It had no structure and was virtually impossible to buy livestock.” To improve things, he took French farmers to Scotland on a study tour, and began travelling to the Wilton Sheep Fair, buying stock and transporting them back on the night ferry.

After four years managing Ferme de Vimer, the opportunity arose to take over the tenancy. So Tim secured a loan and bought the stock. Over time, Tim and Chrissie increased their land to 248ha and their herd to 115 Normande and Holsteins.

They entered a business partnership with another local farmer which raised their milk quota to over 800,000 litres. Their milk remains with the same buyer as when they first moved – a family dairy in Livarot, which makes Camembert and Livarot cheese. Their sheep flock now numbers over 600 and they have 20 sucklers, and grow maize, wheat, and barley.

Seven years ago they moved into cider apples, too, taking over shares in a small co-operative from another farmer and now grow 30-40t of apples a year. Away from the farm, Chrissie teaches English in businesses, including multinationals like Nestlé.

The couple say the experience has been hard work and things haven’t always run smoothly. But it has also been “wonderful”.

“We’d never have had the same opportunity in the UK – for us it was a chance to farm,” says Tim. “It’s a lot harder to start farming in France now,” he says.

“It’s brought our kids up to be open-minded, too,” adds Chrissie. “They like travelling and are open to new things and we’ve met a wealth of people.”

The experience has been a family affair. Chrissie’s brother currently works for them, Tim’s brother owns a house nearby, and their daughters have made their own lives in France with French partners.

France is now home, and while they miss English humour and pubs, they wouldn’t move back. Tim will be farming for years yet to get his French pension, but they plan to remain long after that. “We want to stay in the house as long as possible – hopefully until they carry me out in a box!” says Tim.

‘It was an opportunity with nothing to lose’

‘It was an opportunity with nothing to lose’

Graham and Susan Savage moved to France in 1984 and over 20 years built a successful sheep business and gained the respect of farmers in the area.

The couple had concluded their sheep smallholding in Devonshire was financially unviable when Graham spotted an article on living in France. The country offered cheap loans, land and available tenancies. Farming abroad was not new to Graham, who had worked on farms in Lebanon and Brazil, but running his own farm was.

“We saw it as an opportunity with nothing to lose,” says Graham. The couple decided on Le Limousin, a sheep-oriented region in the mid-west. It had co-operatives on tap, sheep-focused vets, cheap tenancies, abattoirs – and it was looking for sheep farmers.

With their two young children, Graham and Susan bought a farm house and buildings, rented 50ha and took on 300 sheep. “It was basically inadequate and a shock coming from British standards,” says Susan. “All the grassland needed renewing and the soil pH wasn’t great. Most of the farm needed draining, the buildings weren’t good enough and the flock genetics were bad. Our neighbours found us interesting and a novelty, though, so they were very helpful.”

To build the business they improved their grass land, intensified, and bettered their flock genetics by purchasing UK stock. But severe droughts in 1985 and 1986 struck, and getting everything up and running took 10 years.

Doing business through co-operatives simplified things, though. Lambs were collected for the abattoir, and a cheque posted back; another co-operative enabled farmers to share work and machinery. Susan worked as a translator for a farming college, helping other Brits, and Graham became a rep for sheep handling manufacturer Modulamb.

They expanded to 140ha mostly in ownership, increased their flock to 900 ewes, and grew sunflowers and cereals. Progressing was hard work, says Susan, and didn’t leave much time to enjoy the French lifestyle. But their development earned them local respect, and attracted the press and curious farmers.

After 20 years they’d done all the projects they wanted. “We’d built a good business to sell on, and in a way we’d got a bit bored,” says Graham. So they took the opportunity to semi-retire, sold the farm, and moved a few miles away.

They are now enjoying the fruits of their labour and keep their feet in farming with occasional Modulamb work. “Coming here gave us opportunities we would never have had otherwise – and a better standard of living,” says Susan.

They are unlikely to move back to the UK. As they say: “France feels like home now.”

Tips for smooth settling |

|---|

Jo and Roger Fredenburgh:

|

Tim and Chrissie Green:

|

Graham and Susan Savage:

|

Share your thoughts

What do you think about farming overseas? Maybe you have direct experience? Share your thoughts and advice by emailing fwfarmlife@rbi.co.uk or commenting on the Farmers Weekly forums.