How one farmer is using genetics to increase milk solids

Growing demand from his buyer for milk quality has led Andrew Jennings to change his breeding policy and use embryo transfer (ET) to make faster changes in milk constituents.

Conventional ET can speed up genetic production rate fourfold compared with artificial insemination, by allowing specific cow genetics with desirable traits to be multiplied in the herd.

The ET process involves programming a cow with fertility medicines to produce more oocytes, artificially inseminating, collecting the embryos and transferring into a recipient dam (see “Embryo transfer: How it works” below).

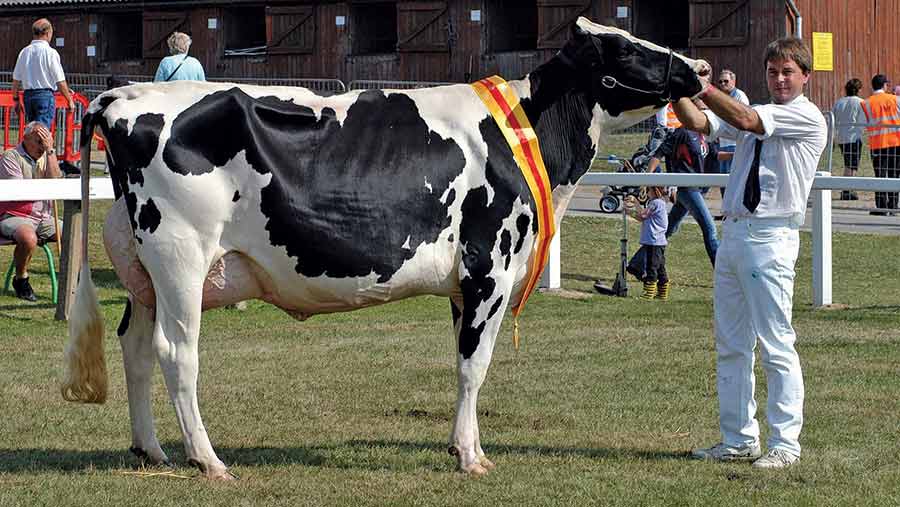

Mr Jennings, who farms in a family partnership at Hill House Farm, Ripon, has used ET in his 200-cow Abbeyhouse pedigree Holstein herd for the past 20 years as a means of multiplying his best genetics.

See also: Expert advice on raising milk fat and protein content

However in the past 24 months, he has decided to shift his focus from selecting for yield, and instead target constituents – something he believes many dairy farmers could benefit from doing.

“Arla doesn’t want quantity at the moment, they want fat and protein and if you produce quantity not quality, you will suffer in milk price,” he says.

“We’re currently on a liquid contract, but we will be swapped over to constituents, so we are taking the long-term view.”

Fat and protein

As part of this strategy, tweaks have been made to cow diets to include wholecrop silage to boost milk fats. At the same time, Mr Jennings has chosen to use genomics, sexed semen and ET to select replacements for longevity, production and milk solids.

“To select the best cows for ET, we look at milk records, back pedigree and breeding values. When we look at records we want five generations of VG or EX behind her and at least 10,000-litre yields.

“In the past 24 months we have also started only choosing cows with over 4% milk fat,” says Mr Jennings.

The herd currently averages 10,000 litres a cow a year at 4.14% fat and 3.09% protein.

See also: Milk fat and protein ratio could unlock herd efficiency

A proportion of heifers and cows will be genomically tested every year as a means of assessing traits such as health, type, milk and constituents, to provide further information to help select the best animals for ET.

Three or four animals will then be flushed every year and sexed semen used to produce replacements.

Although it is too early to see improvements in overall herd milk constituent levels, over the 20 years of using ET, Mr Jennings has seen marked improvements in other traits. This has included improvements in herd classification and better cow longevity.

“We’ve got more cows doing 100t than we did two years ago. They’re also lasting longer so we can sell more heifers and we don’t have as many culls so they have a high value when they leave. Hopefully that means we’re better off on the bank balance,” says Mr Jennings.

Improve traits

Vet Jonathan Statham from Bishopton Vet Group and Raft Solutions believes this is a good example of how producers can use breeding technologies to improve specific traits relatively quickly.

“Farmers can use ET to make improvements in the areas they want and a lot of these areas are commercially focused. It could be that a farmer chooses to select for mobility to minimise lameness, or maybe their priority is milk solids,” he says.

In recent months, Mr Jennings has chosen to put ET on hold as a means of saving money while milk price is low. However, he remains committed to using the strategy in the future and potentially using IVF as a means of speeding genetic progress even further.

Mr Statham recognises that milk price pressures can make it a challenge to invest. However, he believes ET can bring big benefits.

“There’s no doubt it’s a challenge to make investments when costs are under pressure, but if you look to the future, this is an investment that will bring significant return. It’s about investing in the future and using quality genetics to produce quality milk and what the market wants,” he says.

See also: Embryo transfer ‘a faster way to boost beef herd genetics’

The cost of ET will vary depending on vet practice and numbers of cows involved. However, it tends to be about £200-£250 for collection and fresh implantation (including all fertility medicines), plus semen.

With the price of genomic testing and ET coming down all the time, Mr Statham believes this provides more opportunities for commercial farmers to benefit from these technologies.

The fact an animal can also be flushed three to four times a year and still get in calf also makes the process commercially viable.

“We work with commercial farmers who are genomically screening their whole herd and selecting the top 5% for ET,” he says.

“We have relied so heavily on the male side to bring genetics from round the world, but this is about looking at both sides of the equation.

“We can use genomic evaluation to pick the best females, so we no longer need to be held back by the female side.”

Embryo transfer: How it works

1. Donor cow injected with follicle stimulating hormone to produce multiple ovulations – this usually begins between day nine and 12 after a reference heat. This reference heat can be managed by synchronisation.

2. Donor cow inseminated by AI (can use natural service, but AI provides faster genetic gain and option of sexed semen); about three to four straws will be used, split across two days.

3. Eggs fertilised naturally in the cow.

4. Embryos left to develop in cow’s uterus for seven days.

5. Embryos are collected. This involves flushing the uterus with collection fluid – a vet or embryologist will grade the embryos and use the best ones. On average, four “grade one” embryos will be produced.

6. Embryos are put into the recipient or can be frozen for future use – the recipient will have previously been synchronised with hormones so she is in heat at the same time as the donor. A conception rate of about 60% is usual due to the careful screening of embryos and recipient.

Top tips for successful embryo transfer

- All the basic principles of good reproductive management apply.

- Work with your vet to plan an ET programme.

- Ensure consistent nutrition and avoid stressors such as group changes in both donor animals and recipients. Minimise changes six weeks before collection and six weeks after implantation.

- Identify forages and feed in advance to avoid diet changes.

- Don’t overfeed crude protein. Aim for 16% CP of high quality with good amino acid balance.

- Lift ration energy density before embryo collection.

- Optimum cow body condition is a must – target 2.5-3.0 and avoid changes of more than 0.5.

- Managing donors and recipients in a separate group can provide more control.

- Select recipients with good health status and mature body size that can calve naturally.

- Using a heifer as a recipient reduces risk of subclinical endometritis, which may reduce conception rates.

- Ensure good semen quality and handling.