Poultry breeders embrace technical advances

Making genetic progress in broilers is not about pushing the extremes, but more about moving every desirable trait forward in a controlled and balanced way.

In the past, the emphasis was primarily on performance traits, such as meat yield and growth rates, explains Aviagen’s director of global genetics, Santiago Avendano.

But feedback from all stakeholders in the industry – including consumer lobby groups and politicians – has meant breeders have had to broaden the spectrum considerably, to include things like welfare, liveability, reproductive fitness, bird behaviour and environmental impact.

Furthermore, the fact that many traits have what is known as “antagonistic relationships”, means that putting too much emphasis on one area can have a detrimental impact on another area, which may be just as desirable.

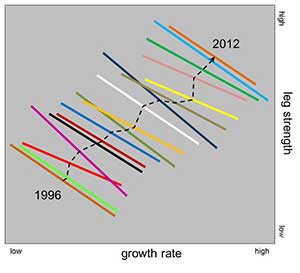

An example of this is leg strength versus growth rate. As the graph shows, in any one year there is a negative correlation between the two – birds with faster growth rates tend to have weaker legs. But with every advancing year, the trend is positive for both traits and the population on average has a better performance in terms of growth and leg strength.

“This is what a balanced breeding programme delivers,” says Dr Avendano. “We always select birds that are not extreme for any individual trait, but are above average on many traits. We test for over 30 traits and put everything into one big equation and make sure it all moves forward in a holistic way.”

Different parts of the poultry industry will have different needs from the bird, he adds.

For example, broiler breeders will be primarily interested in things like egg production, hatchability, fertility and egg shell quality, while broiler growers will want rapid weight gain, good feed conversion, uniformity, skeletal and metabolic fitness, and disease resistance. For the processor, breast meat yield and quality will be important concerns.

These all have to be delivered at the same time, says Dr Avendano. So in terms of the relative weight given to various breeding traits, about a third of the selection pressure goes into live bird performance, a third goes into reproductive fitness and a third goes into welfare.

Breeding methods

To meet these demands, Aviagen has implemented a number of innovative techniques over the years, though there has always been an emphasis on leg strength.

“We have about 40 people in our UK and US breeding programmes whose role is to look for leg deformities,” says Dr Avendano. “If we see any issue physically with a bird, we don’t use it for breeding, even if it has outstanding genetic values for FCR, reproduction or any other trait.”

The company also excludes seemingly healthy birds from the breeding programme if they happen to come from families with a propensity for leg defects.

To make the process more robust, Aviagen started using a Lixiscope X-ray device back in 1989 to detect Tibial Dyschondroplasia at clinical and sub-clinical levels, rejecting any birds with any sign of this condition. The result has been a massive reduction in levels of TD in the company’s breeding stock and their progeny, and the technique has also been extended to its turkey breeding programme. As a result, the TD incidence in breeding turkeys has dropped from about 35% to nearer 5% in just six years.

Another routine check is for oxygen saturation levels in the blood of selection candidates using an Oximeter. This measures the ability of the cardiovascular system to carry oxygen around the body, which is important for reducing sudden death syndrome and ascites.

Birds are only accepted into the breeding programme if they come from families with above average levels of oxygenated blood. Since 1991 this has led to a significant increase in oxygen blood levels and less ascites in the field. “We can now be sure our birds will thrive in a variety of locations around the world, including at high altitude,” says Dr Avendano .

Another key breeding technique has been the introduction of “commercial sibling testing”. “The bird’s performance is determined by both the genetic component and the environmental component. You have to understand the interaction between them and separate these two things out accurately. The same genetics will be expressed very differently in a good environment compared with a more challenged environment.”

Commercial sibling testing makes selecting for contrasting environments possible. While the pedigree selection candidates are tested in a high hygiene environment, which is essential for an assessment of heart and lung issues and leg deformities, their siblings are grown in a non-biosecure environment, essential for improving robustness. This helps identify those birds that will perform well in terms of gut and immune function, liveability, growth and uniformity.

Birds are also monitored for feed intake and growth using transponder technology. This information allows for the recording of feed efficiency in group environments and understanding patterns of feeding behaviour. At the same time, Aviagen has been selecting for low footpad dermatitis in its birds since 2008.

The most recent development, however, has been the introduction of genomics, which has become an integral part of the breeding programme since 2012. This compares the DNA of individual birds and relates it to the traits obtained from pedigree farms.

“Genomics can be used to improve the accuracy of selection for any trait including health and robustness,” says Dr Avendano. “It is especially important in attributes for which there is limited or no individual performance at the time of selection, like reproductive traits, such us egg production and hatchability, which are expressed in one sex.

“Using genomic information we can now predict significantly more accurately the genetic potential for reproductive performance of our male and female selection candidates,” says Dr Avendano.

But, while genomics is a powerful new tool, it is not an alternative to classical breeding, he adds. “It will never replace the 40 people we employ to keep an eye on leg strength nor the wealth of records we gather from our pedigree farms routinely.”

Targeting better feet in turkeys

Turkeys are monitored in a similar way to broilers when it comes to leg strength and feeding, but they are also assessed for their drinking behaviour. “Our studies indicate a link between higher water to feed ratio and wet litter. The aim is to target individual birds generating wet litter and exclude them from the breeding programme.”

Every bird is also assessed for incidence of footpad dermatitis. “Individual footpad scoring, in combination with exclusion of individuals creating wet litter, is likely to be the most effective genetic means of improving gut and footpad health for the future.”

Variation is the key

The rate of genetic progress in broilers over the last 40 years has been nothing short of miraculous. But what is the danger of this advance running out of steam?

According to Aviagen geneticists Anne-Marie Neeteson and Santiago Avendano, it’s not likely at all. Even experiments which focused on pushing just one single trait – bodyweight – found no evidence of improvements plateauing, even after 47 generations.

While selection could potentially give a reduction of variability within line, populations are managed to maintain significant genetic diversity in the long term. In addition, the process of mutation contributes to the creation of new genetic variation every year. “New alleles are being created all the time, albeit at a very slow rate.”

This mutation is fuelling genetic improvement and contributes to the continued heritability of things like bodyweight and egg numbers.

But the two scientists do concede that the loss of a number of alleles could undermine the ability of a bird to deal with new disease threats, which is why it is important to manage genetic diversity carefully and maintain large gene pools.

“The main asset of any breeding company is genetic variation,” they say. “Future genetic improvement depends on it more than anything else. Maintenance of genetic variation between breeding populations and within them is a high priority.”

Definition: An allele is a form of gene, located at a specific site on a chromosome, that determines what traits can be passed on from parents to offspring.

(See our special reports in bird health)