HGCA results question value of micronutrient use

Latest results from three years of HGCA-funded work on micronutrient use in wheat show yield responses being few and far between, suggesting foliar applications are often unnecessary and a waste of cash.

Even crops being grown on trial sites known to be at risk from deficiencies failed to show a yield benefit from foliar applications, which were used at rates recommended for a severe deficiency.

In fact, just one yield response – to copper – was seen over the 15 sites over the three years, confirms the senior principal scientist Steve McGrath of Rothamsted Research, who points out the five sites were chosen to be representative of situations where farmers would be advised to apply micronutrients as a matter of routine.

“In most situations, it seems that micronutrients aren’t limiting wheat yields. That might come as a surprise to growers who have been applying them as a matter of course, having been told otherwise.”

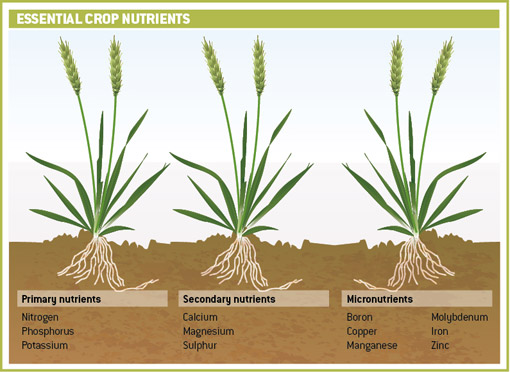

Only manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu) were investigated in the work. Soils were tested to see if their micronutrient status had changed and crops monitored for signs of deficiency and any yield or quality responses to applications noted.

Soil, tissue and grain concentrations of the three micronutrients were measured, with the wheat variety Solstice being grown at all five sites. Of these, soil types included light, organic and calcareous.

“Our interest in this area stems from the fact that most of the micronutrient work still used to give advice on farm was done some time ago, back in the 1960s,” he says.

“There’s very little information on whether today’s higher yielding varieties have a different micronutrient requirement or if they respond more to applications. We have to go back 30 years or so to find any meaningful data.”

Before detailing the latest results, Prof McGrath cautions that some wheat crops will genuinely require micronutrient applications.

“These are usually known about because the visual symptoms of deficiency become so obvious during the course of the growing season and action has to be taken.

“The important advice for these situations is to continue applying the required micronutrient. In certain soils, they can get tied up and are not available to the plant.”

Otherwise, the need for micronutrients is not quite as some companies would have growers believe, warns Prof McGrath.

“Getting just one response from 15 trials equates to between 6-7% of the national wheat crop requiring treatment.”

To help growers understand the practical implications of this figure, he uses sulphur as a comparison.

“Sulphur is a major nutrient and research shows between 30% and 40% of sites growing cereals will respond to additional sulphur. So it’s a very different scenario.”

He does admit, however, that there is still a lower level of knowledge when it comes to micronutrients. “We’re still trying to get a grasp on how prevalent these responses are. But it will be in single figures.”

Finding out if you’ve got a genuine problem is possible with plant and soil analyses.

“And if these tests show you don’t need to top up micronutrient levels, there’s an opportunity to save money.”

Using visual symptoms isn’t quite so straightforward, warns Prof McGrath.

“In our work, we didn’t see them, even where tissue analysis showed some of the crops had concentrations below the required level in leaves and the soil levels were deemed to be low.”

He suspects that tests used to determine deficiency may be pitched too high and believes that more research is needed in this area.

“Soil analysis does give some guidance for zinc and copper. However, it isn’t useful for manganese as concentrations go up and down with soil moisture levels.

“But the thresholds for zinc and copper are on the high side. The barrier could probably be lower.”

The same is true of leaf samples or tissue tests, he believes. “It might be time to look at these again. Low levels didn’t translate into a measureable yield effect.”

The weather can affect micronutrient levels in crops, but not in the soil, he explains. “In a wet year, crops tend to put on lots of vegetative growth, which can have a dilution effect and show up as low concentrations of micronutrients.”

It doesn’t mean, however, that additional applications are required. “In 2012, we saw some of the lowest levels in our tissue samples. But they had no effect on final yields.”

| Getting the values right | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum values for Mn, Zn and Cu in soil (mg/kg soil) | |||

| Mineral | Mn | Zn | Cu |

| None | <1 | <2.5 (if OM>6%) | |

| <1 (chalky soils) | |||

| <1.6 (other soils) | |||

Aid for backward crops

Late-drilled wheat crops with shallow rooting systems will suffer if we have a dry spring, so they will need all the help they can get, particularly as every single tiller will count this year.

A reluctance to spend money on these backwards crops needs to be overcome, says Jim Carswell of Frontier. “Plants with less extensive root systems will struggle to pull all the nutrients they need out of the ground, especially if we have a dry spell.”

In addition, soils are still very cold, so mineralisation of organic matter will have been minimal to date, he warns. “Where straw and farmyard manure have been used, the nutrients won’t have been broken down yet.”

Tissue analysis thresholds

In dry matter:

- Copper <4mg/kg in leaves, <2mg/kg in grain

- Manganese <20mg/kg in leaves and grain

- Zinc <20mg/kg in leaves and grain

Current status of soils

Another part of the HGCA-funded project was to investigate whether the micronutrient status of soils has changed over the years.

Prof McGrath and his team sampled 132 arable soils and compared the results for copper, manganese and zinc with samples taken for the National Soil Inventory between 1978 and 1982.

“The results show there has been a slight decrease in levels over the past 30 years,” he summarises. “The differences were small, but they were there.”

Micronutrients don’t wash out of soils, he continues. “They aren’t lost by leaching. However, deposition fom air used to be greater.”

The combination of better pollution controls and less heavy industry, together with a reduction in coal buning, has been responsible.”The net effect is small. It will take many hundreds of years before any big differences are seen.”

More micronutrients don’t always provide better yields

It is difficult to get significant yield responses from micronutrient trials, says Frontier Agriculture’s national trials manager Jim Carswell.

However, the body of evidence collected over a number of years with a broader range of elements suggests that micronutrient applications do give an economic return on investment, he notes.

“They have to be considered against the background of static on-farm yields. Most farmers have got to grips with variety and spray decisions – leaving them wondering about whether there’s anything else holding the crop back.”

Micronutrients haven’t received the same attention as certain macronutrients in recent years, particularly nitrogen and sulphur, he remarks.

“They have been looked at and the recommendations have been altered in some circumstances. But it hasn’t been fashionable to do the same for micronutrients or to consider whether new varieties have a greater demand.”

That’s why the quest to increase farm output economically has put more focus on micronutrient use, especially as some of the micronutrient products coming through are more sophisticated, he reports.

“The individual farm situation also has a major role, with factors such as soil type and its organic matter content often making quite a difference.

“There’s also interaction between nutrients and the effect of pH – remember that a soil with a high pH tends to reduce the availability of micronutrients, with the exception of molybdenum. That’s the other way round – it gets blocked by a low pH.”

Responses to all micronutrients were lower in Frontier’s 2012 trials, recalls Mr Carswell. “It was in stark contrast with 2011, which was a dry year. It appears that the high rainfall we had last year allowed root systems to grow and prevented soil extraction becoming limiting.”

He agrees that testing can be minefield, as not all the tests are appropriate for individual micronutrients.

“It’s best to work from soil analysis and a tissue test,” he advises. “It helps to take the guesswork out.”

Mr Carswell adds the tissue test should be done at the start of spring. “Take the youngest, fully emerged leaf, whether it’s cereals or oilseed rape. You can then get a broad-spectrum analysis done for a range of elements, so that any issues are identified.”

Should a top-up be required, most micronutrient sprays can be co-applied with the T0 or early PGR treatment, he points out.

“Ideally, trace element requirements should be sorted by the first node stage in a cereal crop. You want to build up levels prior to the maximum demand period, which is when the crop switches into reproductive mode, at around GS 30/31.”

Jim Carswell says there’s increasing attention on the economic case for micronutrient use.

In oilseed rape, the first application should take place at the start of rapid stem extension, with a follow- up 10 days later.

“Get these products on early. Once rapid growth takes place and you see deficiency symptoms, it’s too late.”

When it comes to choosing products, it’s worth looking at the concentration of nutrients contained within them, advises Mr Carswell.

“Manganese products, for example, can range from 200g/litre to 500g/litre. And there are formulation differences to consider too.”

The choice varies from general tonics, containing a whole range of trace elements, to products containing a couple of the main trace elements through to straights, such as boron or magnesium oxide.

“Make sure you use the one best suited to your situation. Use historical evidence, tissue tests and soil analysis to make your decision.”

Philip Hoddy, Birdsall Estate, Yorkshire: Taking a closer look in the field

An unexplained fall in wheat yields at Birdsall Estate on the Yorkshire Wolds in 2011 gave arable manager Philip Hoddy cause for concern and prompted him to seek advice about nutrients.

Busy managing 1,000ha of arable land, he took a closer look when a particular problem was observed in the Group 3 variety Invicta. Not only had it fallen behind in yield performance, the crop was also displaying blind ears.

Likewise, the northern-specific soft Group 4 choice Cassius was also struggling, which he had originally attributed to the dry autumn conditions at drilling. “It never gathered its feet,” he recalls. “Coming into the spring, it clearly needed attention.”

Discussions with agronomist Chris Rigley of Yorkshire Arable Marketing resulted in a new approach with trace elements, having confirmed that soil organic matter levels were low.

“The crop had never really got going during establishment,” notes Mr Rigley. “We needed to accelerate its growth, so decided to feed it from the top.”

Magnesium was chosen as the remedy. Although the soils weren’t shown to be lacking the trace element, it was felt that their calcareous composition was locking up the available mineral.

“The classic sign of magnesium deficiency is chlorosis or yellowing between the leaf veins. That’s because magnesium plays a vital role in photosynthesis, as chlorophyll relies on it.”

Although the crop at Birdsall wasn’t chlorotic, he suspected it was suffering from hidden hunger. “The plant had enough to get by, but it was scrimping. I thought it would make use of more magnesium.”

His unconventional advice was to use a recently launched product, rather than an old favourite, and to apply it earlier in the season.

“The idea behind putting it on earlier was to boost photosynthesis in the plant, even during the minimal daylight of the winter months.”

Mr Hoddy says he was advised to make four applications of magnesium, starting at T0. “That gave us the recommended early start needed and provided some breathing space, should the T1 get delayed.”

Using a formulated micronutrient product was also advised. “As a result, we opted for Safagrow’s Magnesium Aloy, instead of something like bittersalz. It seemed to give the crop the immediate boost it needed, as well as offering a longer term controlled release.”

The product’s better longevity was evident, he adds, which Safagrow claims is due to the surfactants in the formulation.

“You could see that the product was adhering to the leaf, despite the high amount of spring and summer rainfall.”

Another advantage was the ability to tank-mix the product reliably with Adexar (fluxapyroaxad + epoxiconazole), he stresses, without having to worry about solubility in the sprayer.

The four applications subsequently made weren’t scrutinised in a formal trials regime, points out Mr Hoddy, who relied on more than 20 years’ experience of crop growing to tell him about their effect on the crops.

“But we also saw it in the final yields. The Invicta still had a few blind grain sites, but yields were back up to the farm average.

“The Cassius, meanwhile, gave an additional 1t/ha over the previous year, which was against the background of a challenging season when the average yield dipped.”

Keep up with the latest arable news