Opinion: Stephen Carr is reassured by Dyson’s farming losses

© Action Press/REX/Shutterstock

© Action Press/REX/Shutterstock Schadenfreude, a wonderful German word for “pleasure derived from another person’s misfortune”, is not an emotion that I would ordinarily own up to.

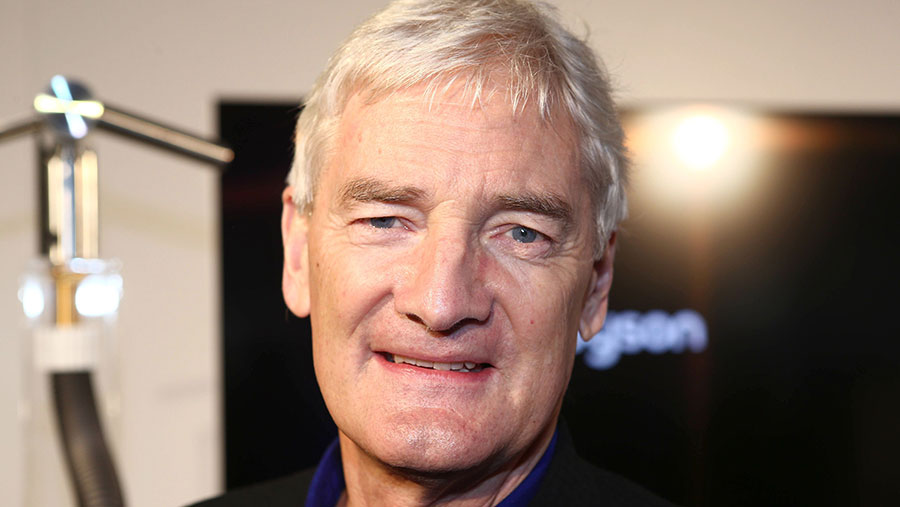

But, as a farmer who has spent rather too much of my life scratching a meagre living growing grain on steep, flint-strewn Sussex downland soil, I have to confess to having had a wicked chuckle recently when Britain’s biggest farmer, vacuum cleaner tycoon Sir James Dyson, announced a loss of £4m. I’m not proud of myself.

Sir James began a spending spree on farmland in Lincolnshire about five years ago and is now thought to have invested an estimated £250m, amassing more than 25,000 acres in that county (with delighted local land agents referring to the “Dyson effect” as land prices were driven up to unprecedented levels).

See also: Greenpeace demands end of area payments, as Dyson nets £1.6m

But why should I gain any satisfaction from learning that Sir James’ massive investment has only led to a huge trading loss – apparently even after he claimed a BPS subsidy of £1.6 million?

After all, Sir James is that most precious and rare thing – a brilliant British inventor and successful industrialist who is simply ploughing some of his profits back into British farming.

Stephen Carr farms 800ha on the South Downs near Eastbourne with his wife Fizz

Stephen Carr farms 800ha on the South Downs near Eastbourne with his wife FizzLack of understanding

I’m not sure that I can even rationalise my unkind enjoyment of Sir James’ difficulties, but I think it stems from the suspicion that perhaps he doesn’t yet understand the subtleties of our farming craft.

Yes, he’s been careful to buy some of the best land in England, built a state-of-the-art grain store and even invested a staggering £5m on improving land drainage.

But what he is now discovering, to his cost, is that simply investing large amounts of money in agriculture is not any guarantee of success.

In other industries, perhaps, if one invests enough money into R&D and efficient, low-cost modern manufacturing facilities, profits will flow.

But in farming, the more buildings one erects, the more concrete one pours, the more machines one buys and the more highly qualified the farm managers one hires, the larger one’s trading losses can easily become.

‘Innovative farming for the future’

I am not saying that Sir James necessarily falls into this category, but a visit to the website of his farming company, Beeswax Dyson Farming, did cause me to wonder. Beneath a splendid heraldic shield, visitors are greeted by a declaration that reads “Innovative farming for the future”.

Click on “Farming” (rather than “Renewable Energy” or “Estate”) and you are taken to a page headed “Purpose and Vision”. Beneath is a picture of a tractor and drill train so long that I don’t think they would get into some of my fields before they would be leaving at the other end.

Further down, under a headline declaring “Another productive harvest”, is a widescreen photo of a vast array of harvest machinery that includes five combines and 10 tractors with a huge grain silo in the background.

In the foreground stand two muscular 4x4s from which, presumably, Sir James or his farm managers direct epic-scale harvesting operations.

By way of contrast, I gathered my 2017 harvest with a 20-year old John Deere combine and am now storing my grain in a shed that I adapted to a grain store 20 years ago using salvaged materials and a second-hand dryer with ducting that I picked up dirt cheap at a local farm sale.

With spot feed wheat prices currently back to little more than £130/t, no doubt both Sir James and I will both be struggling to make a profit from our respective 2017 harvests.

But my gloom has been greatly lifted by the knowledge that, in my ongoing vain struggle to avoid producing grain at a loss, I am at least in very glamorous company.