Argentina: A land of profit and problems

A regular contributor to Farmers Weekly‘s Farmer Focus column, Argentine arable farmer Federico Rolle farms some 1,560ha (3,852 acres) across the central provinces of Santa Fe and Santiago del Estero.

Compared with other farms in the region, it’s not a huge area, but with the land spread over 500km on three different sites, management can be tricky.

“The development of GM soya and maize in the past 10 years has made cropping incredibly profitable here,” explains Mr Rolle. “As a consequence, we’ve seen land prices rocket up. So, to expand you have to take new ground where you can find it.

“For me that has meant looking further afield to the less fertile areas to the north. When I took it on four years ago, the land had only recently been broken, having previously been dry forest and scrub.

“Less rainfall, shallower topsoils, lower organic matter and high levels of salt mean it has almost half the production potential of land around my hometown of Rosario.”

Although his roots lie in farming, Mr Rolle admits he was prompted to return to mainstream agriculture as profitability rose on the back of improving soya margins.

“With two brothers, our family farm is divided up. At just over 60ha (148 acres), my share isn’t viable as a stand-alone business.

“For years I put it out to contract and worked outside farming, but in the 1990s realised there was a big opportunity in share-farming and set about securing more ground for a larger scale farming venture.”

Having originally trained as an agronomist, he started out working for a farmer co-operative, bulk-buying inputs such as seed, fertiliser and sprays. While doing this he studied for an MBA at the Harvard Business School in Buenos Aires. This quickly led him into a position as agricultural manager for a provincial bank. Mr Rolle took on a part-time role with Brown and Co, allowing him the opportunity to develop his own farming enterprise further.

“My job as Argentine agent is to promote the country’s farmland to European investors. Being a farmer myself puts me in a strong position to speak from a practical viewpoint.”

Mr Rolle’s share-farming agreements for the land around Rosario and to the north, around Bandera, are similar in structure, with just one major difference. While both are based on a “rental” payment as a percentage of total annual revenue from the crop, that percentage reflects the fertility of the land.

Yields on the more southerly ground tend to be at least one-third greater than those of the less fertile land to the north. Consequently, Mr Rolle hands over 36% of the value of the crop every year to his farming partners around Rosario, while those that own the less productive northerly ground receive just 20%.

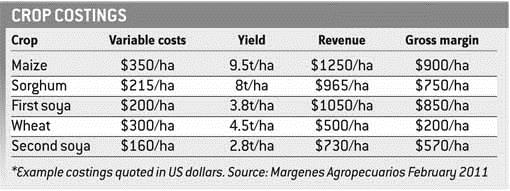

With soya and maize offering by far the best margins (see crop costings box), it is no surprise they are the focus of most Argentine farmers’ crop rotations. And that’s where South America’s climate gives its growers the trump card.

Wheat sown in June is harvested in November (with average yields of 4t/ha), allowing a following crop of soya to be planted.

This double-cropping enables the region’s producers to significantly boost their margins, with second-crop soya requiring virtually no fertiliser and yielding just 1t/ha less than first crops (at around 3.4-3.8t/ha).

Most rotations therefore comprise a crop of maize or sorghum followed by a first-crop soya. Wheat tends to follow this and, in that same year, a second-crop soya is drilled. The land then returns to maize or sorghum – a three-year cycle.

Some growers, particularly those further south, extend the rotation with a further cash crop – sunflowers.

Mr Rolle employs a complete zero-tillage system. Seed and fertiliser rates vary depending on weather and soil type, but the typical rate for a 4t/ha-yielding wheat is 200kg/ha of urea with 100kg/ha of DAP – the entire crop requirement for the growing season applied either at drilling or direct to the seed-bed.

Studies from Argentina’s main government-run research organisation – INTA – show direct drilling, which is used across 70% of Argentina’s cropped land, typically improves yields by 20%, at the same time slashing establishment costs by 60-70%. Much of this improvement is put down to reduced moisture loss – critical in the high temperatures of an Argentine summer.

Direct-drilling, of course, brings one great advantage to the country’s arable growers – fixed costs are kept to an absolute minimum.

But it’s not all roses. Argentina’s current government is well aware of the profits being made by the country’s soya and maize producers and consequently imposes heavy export tariffs on the most lucrative crops.

At 35% for soya, 32% for sunflowers, 23% for wheat and 20% for maize and sorghum, these “retention taxes” are imposed on the gross revenue generated before costs are allocated to that crop.

Therefore, if growing costs are within 35% of the total revenue from a particular enterprise, then it is possible that it will result in a net loss. In addition, farm businesses are liable for a 35% tax on profits.

To compound matters, in the last three months, the country’s ministers have imposed a ban on the export of maize and wheat to try to limit increases in domestic prices. Inflation is estimated to be about 25-28%, although the current administration does not acknowledge this.

“We have 500t of wheat left on-farm from the last harvest, but if I want to sell it I will get 20% less than the current world market price,” says Mr Rolle.

“We are controlled by this government’s policies on agriculture, and if world soya and maize prices were to fall we would be crippled,” says Mr Rolle.

“But for now we are fortunate that the crops are very profitable, thanks to our kind climate and low growing costs.”

GM crops – the future for farming?

Since their introduction some 20 years ago, GM crops have been wholly embraced by South American farmers. For Argentine growers this new technology has been the ideal partner for their low-cost, zero-tillage approach.

Round-Up Resistant (RR) maize and soya can be found on almost every farm. But what are the pros and cons of the new technology?

Advantages:

* Weed control is no longer an issue. Can now focus on drilling at the optimum time, critical with the region’s rainfall patterns, rather than the focus on getting a clean seed-bed

* No-Till synergy – without weed control issues straw and chaff can be left on the surface helping to limit moisture and organic matter loss as well as wind erosion

* Reduces chemical inputs by 40%

Disadvantages

* In maize, the genetics can degenerate over time, so home-saving seed is not an option. This is not a problem in soya, but there is a lack of clarity over royalty payments

* There are reports of some strains of wild sorghum developing round-up resistance

* Requires ongoing scientific evaluation and chemical development to keep one step ahead of nature in limiting herbicide resistance

Federico Rolle’s view:

“GM crops have been the key to the success of farming here in South America. Without RR varieties, zero-tillage just wouldn’t work.

“We have a much lower workload thanks to the combination of no-till and GM, which means crop establishment is easier and faster, so we can cover more ground. That gives us the potential for expansion and better use of machinery and labour.

“However, we must have controls in place and continual scientific evaluation to protect the consumer and the environment.

“In my opinion, GM is just the first step in a global revolution of agriculture.”

Farm facts

* Total area: 1,560ha (3,855 acres)

* Location: Tortugas 60ha (150 acres) owned and Bigand 500ha (1235 acres) share-farmed close to Rosario, Santa Fe province, central Argentina; 1,000ha (2,470 acres) share-farmed near Bandera, Santiago del Este province (500km north-west)

* Soil types: Rosario – deep mineral Pampa soil – 30% clay, 30% sand and 30% loam with 3-4% organic matter; Bandera – shallow mineral soil with heavy salt fraction (limits production potential by 50-70%)

* Rainfall: Rosario – 1,000mm/year (70-80% falling between Sept and March); Bandera 800mm/year (80-90% falling between October and March)

* Cropping: 1,000ha first-crop soya, 250ha wheat followed by second soya (double-cropped), 310ha maize/sorghum

* Machinery: Tractors – 160hp Pauny EVO, 160hp Zanello artic; Combine – 5-walker Don Roque 125-M with 7m (23ft) header

* Staff: Federico Rolle and partner Lisandro Macchia part time plus two full-time tractor drivers