From lab to launch of new active ingredient

It takes around 10 years to get a new active ingredient from the lab to product launch, so predicting what future standards will have to be met is something of a lottery that appears to be slowing the once regular flow of new agchem products to market.

“Europe is probably the most highly regulated region globally and these regulations are getting more complex and changing quickly,” says BASF fungicide specialist Rosie Bryson.

She estimates the cost of developing a new active ingredient has risen from around €200m (£169m) to nearer €250m (£211m) over recent years, largely due to tighter regulations and requirements for more testing (see box).

“Everyone focuses on the efficacy of the chemistry, but in reality that’s only about a third of the development cost. Examining the biology – its activity and movement in the plant and effects on different plants – is another part, and regulatory aspects, such as residue testing, toxicology, environmental fate and impact on non-target organisms, make up the final third.”

The development process

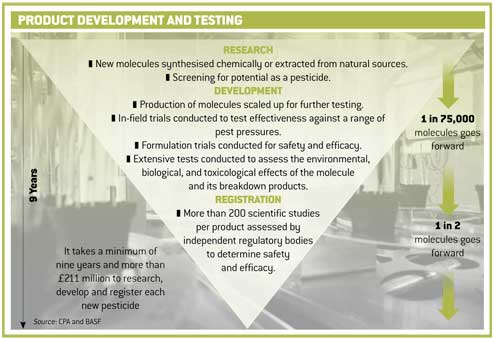

The research and development of any new active ingredient starts with a pre-screening process that typically examines the characteristics of some 150,000 different natural or synthesised molecules, Dr Bryson explains. Much of this process is now highly automated and will select the most promising substances for the next stage.

About 20,000 substances go on to be examined in more detail using lab-based tissue cultures to test their biological activity, before just 1,000-2,000 go on to be scaled up and tested in greenhouse trials. From there, about 100 or so go forward into field trials, before eventually just one or two will be selected to make up the final pesticide product.

These active ingredients will be tested at different formulations to find the optimum balance for both efficacy and safety, before being tested for around two years in field trials. The optimum formulation will be the one that is submitted to the relevant regulatory body (such as the Chemicals Regulation Directorate) for approval, so extensive tests will be carried out to assess the environmental, biological, and toxicological effects of the molecule and its breakdown products.

Approval process

Before any pesticide product can be used, sold, supplied, advertised or stored in the EU, it must be authorised for use (this includes natural, organic or biopesticides). Substances must be proven safe for people’s health, including their residues in food and effects on animal health and the environment.

There is a three-stage system in Europe for this approval process whereby based on evaluation by the designated Rapporteur Member State (RMS) and after a qualified majority vote of EU member states the European Commission approves the active substance. The Zonal Rapporteur Member State (ZRMS) will evaluate the core dossier for a formulated product for use in that zone. This is followed by individual member state evaluation of any national requirements and national authorisation. This cannot be granted until after approval of the active substance.

The EC says that under new EU rules, it takes 2.5 to 3.5 years from the date the application is accepted to the publication of a regulation approving a new active substance, although this varies greatly depending on how complex and complete the dossier is.

To get a pesticide product approved in the UK, manufacturers must submit a detailed application to the Chemicals Regulation Directorate (CRD) that includes all information and data needed to meet EC regulations.

This includes data and supporting trial results on a wide range of areas, from the physical and chemical properties of the product, toxicity, residues, environmental fate and behaviour, ecotoxicology, efficacy, and operator guidelines (see box). “On average around 800 studies are filed for a typical product registration,” says Dr Bryson.

An outline of the data required to support any application is available in the 191-page Data Requirements Handbook on the CRD website (see links below).

Once again, the cost and time taken to register a product varies considerably depending on the type of formulation, complexity and amount of data to be evaluated.

When the product is approved for use, it is automatically given a unique registration number, allocated at the time of the first commercial authorisation for that product. This registration number is also referred to as a MAPP (for products authorised after 1 July 1999) or MAFF (before 1 July 1999) number.

Regular reviews

Approvals of new actives are for up to 10 years and must be re-registered for use beyond this to ensure that all relevant risk assessments remain up to date. A new MAPP number will automatically be issued for each product at re-registration.

Dr Bryson says the re-registration process is getting increasingly difficult as rules change and regulations become stricter. “A lot of products were developed at different times and there can be thousands of different data sets to analyse.”

The EU drive towards a more harmonised product authorisation process across member states within three geographical zones (north, central and south) also creates added challenges for manufacturers, she notes.

Under this system, if any one designated member state in one of the three zones evaluates and authorises a product, other member states within that zone can potentially authorise that product based on the assessment of that designated member state.

“The EC wants to encourage ‘zonal dossiers’ which means we [manufacturers] have to try and get a better understanding and demonstrate how products will work across the different European countries making up each zone.”

This means overcoming sometimes big differences in climate and geography, which can affect how products perform, but also raises issues when it comes to what is defined as a “minor” and “major” crop in each country (for example, rye and triticale may be minor crops in the UK, but are more widely grown in other countries that fall within the same EU zone).

There is also a host of other regulations, such as a possible ban on endocrine disruptors, stricter requirements on bee safety and the Water Framework Directive, that will challenge the future development of new actives and products, says Hazel Doonan from the Agricultural Industries Confederation (AIC), which represents the agri-supply industry.

Tests and studies required for a new plant protection product

Colour, odour, solubility – to guarantee consistent composition and quality of product – essential when scaling up production

Used to determine purity and potential residue detection

Acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) toxicity assessed for humans and animals. Metabolism studies assess what happens to the product once it has entered an organism, its movement, absorption and how it is degraded and excreted

Assess the fate of a product in the soil, water and air, but also any potential effects on birds, bees, aquatic species and other non-target organisms

Demonstrates that the product performs in its expected role controlling target weeds, pests or disease

Further information

European Commission: http://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/index_en.htm

HSE pesticides homepage: http://www.pesticides.gov.uk/guidance/industries/pesticides

CRD data requirements handbook: http://www.pesticides.gov.uk/guidance/industries/pesticides/topics/pesticide-approvals/pesticides-registration/data-requirements-handbook/data-requirements-handbook-contents.htm)

European Crop Protection Association: http://www.ecpa.eu/files/attachments/Registration_web.pdf

UK Crop Protection Association: http://www.cropprotection.org.uk/media/1972/introduction_to_ppp_november_2008.pdf