How does your farm’s performance measure up?

The gap between top-performing farms and average ones is large and those poorer performers need to improve their management to hit key benchmarks for yield and margins.

Despite plant breeding and agronomic improvements, variation in yields and margins still differ significantly and by far more that can be explained by soil type and climate.

Adviser group ProCam is using its 10-year database to benchmark individual farms using regional and national data on factors such as yields and costs.

“Even neighbouring farms, with identical growing conditions, can produce very different results,” say Tony John, the company’s director of marketing and technical services.

“It’s not just down to scale – some of the best-run small farms are producing better margins than large-scale farming businesses,” Dr John adds.

He believes standards of management make a clear difference and points out that an understanding of the measures of efficiency is important.

“It’s a practice adopted by other industry sectors under the heading of benchmarks, or KPIs (key performance indicators),” he says.

The same principles can be applied in crop production, providing there is historic evidence of performance, together with results achieved by similar enterprises in the region.

“That’s where our 4cast agronomy database can help. It looks at results from a 10-year period from one region, and then cross references this with the national picture to build a set of benchmarks for an individual farm.”

Benchmarks are usually made up of top-line figures, such as output based on yield, area and revenues, linked to cost targets for seed, sprays and fertilisers.

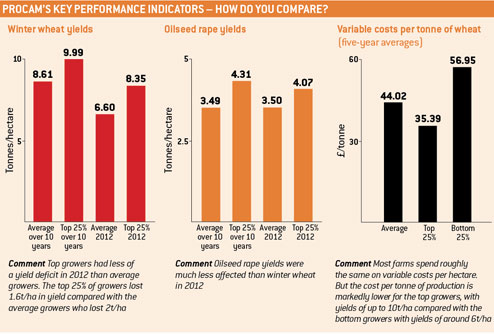

By focusing on the top 25% of performers, the firm has come up with a series of KPIs for each crop, with agronomy programmes then being tailored accordingly.

A significant benchmark is cost per tonne of production – it’s considered better than margin per hectare because growers can’t really influence the price that they get paid.

The 4cast results show that for the top 25% of producers it is close to £40/t, while for the lower 25% it is around £60/t.

A closer look reveals that management is the key differentiating factor – which is where spray timings, intervals, product choice and application rate come in.

“It’s not just down to scale – some of the best-run small farms are producing better margins than large-scale farming businesses”

Tony John

“Putting advice into action and managing an agronomy programme properly is how you create an advantage, rather [than] being too concerned about your spend on inputs. “After all, in most years, a full fungicide programme will deliver a 1t/ha yield response on average,” Dr John says.

ProCam figures show spray costs per tonne for its top 25% of wheat growers were £20.47/t over a five-year period compared with £21.99/t for average growers, illustrating that even though its top growers spent more on sprays, this was more than offset by higher yields.

It also measured that wheat growers lost an average of 0.38t/ha in yield by extending their fungicide spray intervals to more than four weeks, using its 10-year figures.

The group commented that keeping spraying intervals tight will be even more important this year with the decreasing curative impact of the major triazole group of fungicides.

What about the weather?

As 2012 showed, the big variable is the weather. But nailing down some key targets and working to these will have significant advantages in any year.

“Benchmarks can be financial, physical or based on key timings. And management decisions should never be based on one year. That’s why 10-year data is behind our profile benchmarks – they show up most of the variables, which have to be considered,” Dr John says.

He adds that it’s much easier to manage a bad year, such as 2012, when just one or two variables need to be dealt with, rather than 10, which may come all at the same time.

“Losses through missing key dates or stretched intervals can have a significant effect on the bottom line,” he says.

How to maximise your oilseed rape crop