Nozzle choice crucial for faster crop spraying

Modern crop protection products will usually deliver acceptable results provided they are applied at the right time, in reasonable conditions with well-maintained equipment.

Outstanding results, such as those needed to curb blackgrass populations or keep crops disease free when all around are succumbing, need a better understanding of the finer details of application.

Core advice on applying pesticides correctly to ensure optimum product performance and the most effective control of weeds, pests and diseases has remained largely unchanged for several years (see panel), says Syngenta’s application specialist Tom Robinson.

“However, application techniques are continually evolving. Today’s bigger machines are covering bigger areas at higher speeds, helped by continuing improvements in sprayer and nozzle technology.

“The days of applying all pesticides using flat fan 04-110deg nozzles at 8kph at 2.5 bar in 200 litres/ha of water are gone. Precision application at high speeds is now the name of the game.”

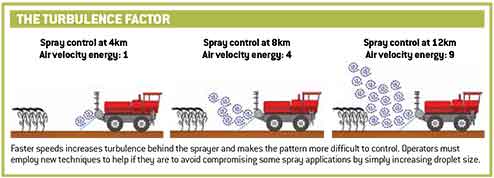

Although precision and speed are not mutually exclusive, spray behaviour is compromised as the sprayer travels faster, says Mr Robinson. “As forward speed increases, more of a horizontal trajectory is put on to sprays. Higher speeds also create more turbulence; it goes up by the square of increase in forward speed, so doubling the speed creates four times the turbulence. Light, slower-moving drops are caught up in it and are left hanging, leaving them more prone to drift.”

Although lowering the boom, decreasing pressure, choosing a coarser nozzle or slowing down can help offset the effect of high forward speeds, any of these measures can also affect spray quality, Mr Robinson explains.

One way to reduce drift is to use nozzles that are inclined from the vertical and produce sufficient directional energy to cancel out these faster forward speeds, such as the Defy and Amistar Go Faster air-induction nozzle. Both are suitable for speeds up to 16kph.

Sprayers capable of 30kph are now on the market and application techniques will need to evolve, says Mr Robinson. “We did this when developing a go faster variant of the Amistar nozzle, adjusting the angle to compensate for the forward speed and make the spray fall vertically. The same principle will be used to produce a new nozzle capable of accurate application at much higher speeds.”

Choosing the right nozzle for the job, as well as the sprayer, is also key, says Mr Robinson. Cereal pre-emergence applications should kick off with a nozzle designed to apply an even coverage to bare soil. This has been shown to improve blackgrass control from 55% to 85% resulting in a threefold reduction in seed return, compared with standard flat fans.

For pre-emergence sprays, nozzles should be angled alternately forwards and backwards along the boom to improve coverage of clods, Mr Robinson advises.

“Early post-emergence all nozzles should be angled forwards for maximum deposition on small grass weeds, then forward and back for all other applications. A water volume of 100 litres/ha applied at 12-14kph is ideal.”

Variable pressure angled fan nozzles such as the Defy should remain on the sprayer up to and including T0 applications, then replaced by an air induction nozzle (such as Amistar) for improved penetration at T1 and T2. This nozzle, with its bigger droplet spectrum, is also a better choice for broad-leaved weeds, he notes. “It gets pesticide into the crop where it is needed, but the air contained in droplets acts as a shock absorber so they are retained well.”

Going back to the angled fan nozzle facing forward and back is the best choice for T3 fungicides. It also suits late aphicide applications, Mr Robinson adds.

Oilseed rape growers should use alternating angle fan nozzles for pre- and post-emergence sprays, switching to the air induction nozzle if spraying conditions become marginal. For all spring applications the angled fan nozzle is favoured, and the potato nozzle for desiccation.

Advances in technology and systems

While nozzle development will help meet the requirements of faster and bigger sprayers, advances in sprayer technology and systems will also be key, says Paul Miller, application specialist at NIAB TAG.

Timeliness is the all-important driver as it is crucial in getting the best out of pesticides, says Prof Miller. Increasing work rates to make the best of available spray windows is an obvious way to improve it, he adds. “I can see the scale and speed of spraying machinery continuing to increase.”

Significant advances in boom and vehicle suspension and the adoption of GPS means 15-16kph spraying speeds with booms of 40+m are now possible. How much wider booms can get is open to question, he says.

“Carrying these wide booms at 0.5m above the crop when using 110 degree fans is difficult, especially on undulating ground. Booms might be carried higher in future, using 80 or even 65 degree nozzles, such as in the USA, but developed to deliver the right spray quality over a wide range of speeds and conditions.”

Higher speeds displace more air, and there can be adverse effects on spray quality. “As you go faster you use bigger nozzles and a coarser spray,” he says. “But there is a limit, and the challenge is to achieve a spray pattern that delivers good efficacy by developing nozzle technology and the application machinery itself.”

Studies are continuing at NIAB TAG, but it seems both air displacement and shrouded wide-boom sprayers are likely to be ruled out, on the basis of cost, weight and, with the latter, difficulty in folding and shroud contamination – this increasing downtime and washings.

Electrostatic sprays, where droplets are given a positive charge that the negatively charged crop attracts, might be another solution. However, these work well on individually spaced plants and are being used and developed in high value crops like fruit and veg, says Prof Miller.

“Once crops develop a canopy there is almost no advantage in terms of deposition, compounded by the fact you have to use lower volumes and small droplets. Work is continuing but we are not likely to see anything in arable crops in the near term.”

Getting a big, heavy sprayer up to working speed brings its own problems. Nozzle clusters that allow sprayers to deliver acceptable spray quality whether pulling away or running flat out are being introduced and are likely to be a key area of development, he believes. Appropriate working pressure ranges can be set for each nozzle and the system selects the appropriate one to suit a certain speed range. Once forward speed reaches a point where spray quality starts to deteriorate beyond set parameters the next nozzle clicks in.

“We have to explore new approaches in machine and systems design to enable operators to spray wider, faster and at lower water volumes while keeping sprays within crop boundaries – the need to minimise environmental and human safety risks when using pesticides is likely to continue to increase,” says Prof Miller.

“We are likely to see a series of developments rather than a major change in approach to the way sprays are applied to arable crops.”

Spray targets

Spray targets vary enormously throughout the season, and include the soil surface, tiny weeds, upright cereal crops and the horizontal leaves of oilseed rape and potatoes.

“Retention, coverage and distribution are all important in varying degrees and choosing the correct nozzle is crucial to deliver the optimum droplet spectrum,” says Mr Robinson.

Retention

• Fine droplets required on difficult-to-wet plants like blackgrass, and wild oats

• Coarse droplets are well retained on easy-to-wet plants like mature cereals, many broad-leaved weeds and potatoes.

• Adjuvants and air-induction nozzles improve retention of coarse drops

Coverage

• Halving drop size increases drop number by eight

• Coverage can increase four-fold

• Fine sprays can be difficult to control. In practice, increasing the water volume is the only way to increase coverage

Distribution

• Coarse drops penetrate upright crops (cereals) well

• Fine drops move horizontally – can use to penetrate potatoes and oilseed rape

• Angled nozzles are more controllable than fine sprays for horizontal distribution