Soil fertility key to building organic yields

With no let up in sight for buoyant grain markets, our organic Management Matters farm hopes further building of soil fertility will yield bigger returns this season. Paul Spackman reports

The dramatic upturn in organic and conventional cereal prices over the past year has proved a mixed blessing for Clinton Devon Farms manager George Perrott.

Having converted to organic farming four years ago and taken the resulting hit on yields, he is pleased the organic wheat price has risen to around £300/t, from nearer £180/t last August. But with 500 dairy cows to feed and the lower crop yields under the organic system, there is not much of a surplus left to sell from the 285ha of arable land.

“We try to keep a buffer of 200t of cereals and will decide in May or June whether to hold onto it, or sell it,” he says. “I’m nervous that if we go into another spring/summer like last year, early yields of grass might not be good enough and we’ll face another tight year for feed.”

The situation has been compounded by an unusually harsh winter which has put significant pressure on all feed stocks. In response, Mr Perrott says cull cows are being sold earlier than normal and he has also halved the sheep flock with the sale of 400 ewes in a private deal with another organic farm.

“It gives us money in the bank and the lower stock numbers reduce the pressure on remaining feed stocks, especially silage bales, which were getting very tight,” he explains. “We’ve been getting up to £950 a head for barren cows, so it seems stupid to keep them any longer than is necessary.”

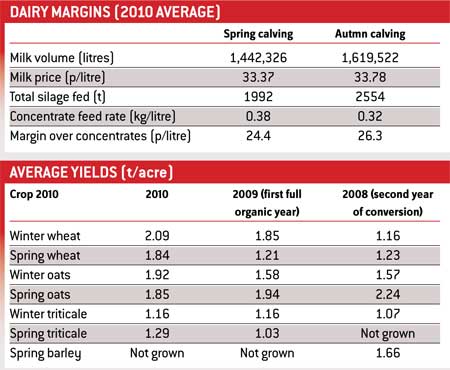

All home-grown cereal feed is costed into the dairy enterprise at the going market price, so the recent upturn in prices has dented margins for the two 250-cow dairy herds. Mr Perrott says the margin over concentrate costs for the autumn calving herd averaged 26.3p/litre last year, while the spring calving herd realised a margin of 24.4p/litre, as more feed was used through last summer’s dry spell.

“You’ve got to look at the whole picture rather than individual enterprises,” he says. “It was the milk price that drove us to switch to organic – that’s still 10p over conventional milk. We’re not getting double the conventional cereal price, but as long as there’s enough of a premium to make up for the drop in yields, then organic is the right thing to do for this farm.”

Building fertility

Mr Perrott is also confident that arable yields are on the up, as soil fertility improves across the farm, which is now in its third year of full organic status.

“It’s a six-year rotation, featuring winter and spring wheat, oats and triticale, plus a three-year fertility building grass/red clover ley. Not all the land’s had the fertility building yet, so I’m confident there’s more yield to come.”

Winter wheat after the clover ley averaged about 4.9t/ha (2t/acre) last harvest, up from 2.9t/ha (1.16t/acre) in 2008 – the second year of conversion (see table).

“Even with conventional production methods we struggled to get 3t/acre on our light land, so I’m really pleased with how the rotation’s performing. If we can get £300/t, that’s double the conventional price, plus we have very few variable costs. I reckon our winter wheat gross margin will be about £520/acre this year.”

All seed is home-saved and this represents the main input cost at around £54/ha (£22/acre) – based on a rate of 200kg/ha and including £36/t for cleaning and £40/t for royalties.

“We normally plough in September, leave it for a month to let weeds germinate, then power harrow and drill from mid-October before shutting the gate,” Mr Perrott says. “There’s an added cost from a bit of slurry tanking, combining and grain handling, but otherwise costs are pretty low.”

It is important that spring-sown crops don’t go in until the soil is warm enough for crops to get away quickly ahead of weeds, he adds. “Typically, we’ll wait until March and plough and drill fairly close together. We have drilled into the first week of May, especially where land has been badly poached by cows. This tends to go for whole crop silage, before going back into grass by early August.”

As part of the organic certification process, one third of the farm is soil tested for nitrogen, phosphate, potash and pH levels in late January and Mr Perrott uses this information to target slurry applications. “Slurry sampling has shown on average about 1kg of available nitrogen per cubic metre of our separated cow slurry.

“The inherent soil fertility isn’t too bad across the farm; most fields are probably Index one or two, while those nearer the dairy are much higher at threes and fours. We had to put extra manganese on some spring oats last year and will do again this season – you’re allowed to use manganese in the organic system, provided it doesn’t contain any nitrogen.”

Weeds and disease

Weed and disease pressure under the organic rotation is generally not too bad, although Mr Perrott says it is crucial weeds are not allowed to get away in mild, wet autumns on overwintered stubbles.

Docks, runch, charlock and thistles are an issue on certain fields, he acknowledges, plus some more fertile land can see a large volunteer population emerge after harvest. “We’ve used this to graze some fitter, fatter ewes in the past, so at least we’re getting something from it.”

Couch is also an increasing problem, but three years of clover tends to smother it out, provided decent ground cover is maintained, he says. “Last year we took silage off some fields, which let the light in and did nothing to help couch control.”

Mr Perrott reckons the lower disease incidence is largely because the crop canopy is thinner and not as lush as under conventional systems. “We haven’t noticed any issues with aphids either, but have seen a larger population of predators such as ladybirds, which could be having a benefit,” he adds.

More information on other Management Matters farms

More information on Clinton Devon Farms