Take P and K fertiliser holiday with care

Insufficient attention to crops’ base fertiliser needs can leave growers with unexpectedly poor yields.

That’s the warning from nutrient specialists – especially to farmers who have taken so-called P&K “holidays” recently and who may have baled more straw than usual this summer.

It comes against the background of a steady fall in the area of arable land in England and Wales receiving manufactured P&K fertilisers since 1985 – the year following the bumper harvest of 1984.

British Survey of Fertiliser Practice (BSFP) figures show that between then and 2009, the area treated with P and K dropped by more than half and rose only slightly in 2010. By contrast the areas receiving nitrogen and treated with farmyard manure remained almost unchanged.

Only in Scotland is the picture significantly different, with fertiliser P&K inputs barely falling over that period.

The AIC’s Jane Salter reminds growers that yields can only rise to the potential of the most limiting factor.

“We face the challenge of ‘sustainable intensification’. This requires the farming industry to optimise output to feed a growing world while safeguarding the environment in which it operates.

“Such optimisation can only be achieved by ensuring crops [and grassland] have an adequate balance of all nutrients.

“It’s clear that the trend in phosphorus and potash use in relation to the maintained nitrogen application rate is not sustainable.”

Chris Dawson, of the Potash Development Association, acknowledges that many growers, in the face of recent fertiliser price hikes, have taken what they perceive as input “holidays”.

“But I maintain that ‘holiday’ is the wrong word. It’s a euphemism. What they’ve really done is sell some of their basic resources.”

That is because crops not getting adequate annual dressings of potash and phosphate must draw on soil reserves, so lowering fertility and eventually jeopardising output, explains Mr Dawson.

Daily wheat demand for potash in May can be three times that for nitrogen, and soils with low K indices simply cannot provide enough, he points out.

Growers hoping to avoid the inevitable penalties arising from low soil P&K indices should regard restoring levels as a capital expense, he advises.

“It’s unfair to expect the crop to bear that cost.”

Trying to save money by drip-feeding only a little more P&K than the crop requires each year on low index soils is false economy, he believes.

“The longer the soil is deficient the greater the potential cumulative cost of any annual loss of yield and quality. In most cases it shouldn’t take more than three or four years to correct a potash deficiency.”

Growers need not be concerned that seemingly heavy applications may lead to nutrient leaching, he adds. “Any losses will be minimal except on true sand soils.”

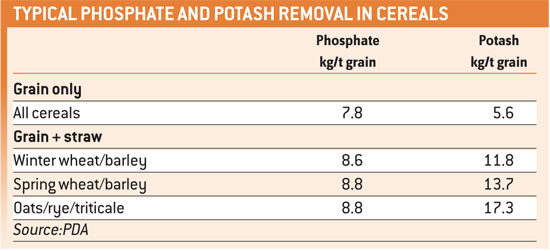

In calculating application needs growers baling straw should remember that its potash content can vary considerably, says Mr Dawson.

“Higher than average rainfall between crop ripening and baling reduces the content. But when baling you can take away twice as much as when you harvest just the grain.”

In Scotland, where BSFP figures show only a very slight decline in the use of P&K over the past decade, average yields for winter wheat, winter barley and oilseed rape have exceeded those in England and Wales by 0.5, 0.9 and 0.3t/ha, respectively, he notes.

“Of course Scottish yields are expected to be a bit higher thanks to the usually longer grain fill periods, but these differences look quite large and merit discussion.”

So given the current price of fertiliser, particularly potash, how should growers determine their needs, what are the most cost-effective products and when should they be applied?

Independent adviser Ian Richards of Ecopt warns that P&K reserves, especially on lighter soils for potash and heavier soils for phosphate, can soon be depleted by high-yielding crops.

Higher crop prices mean the economic advantages of correct P&K use should be greater than for some years, he notes.

“Regular soil sampling is the key and typically costs less than 20p/ha a year.”

However, the annual survey of soil analysis by the Professional Agricultural Analysis Group has shown that only 10% of more than 100,000 samples were at the optimum indices for both P&K.

“Some 90% of samples indicated scope for reducing fertiliser use and costs where at least one index was high, or for increasing fertiliser use and reducing risk to yields where an index was low.

“Where the index is below target (2 for P and 2- for K), it’s usually best to apply phosphate and potash to the seed-bed. But when the application is simply replacing crop offtake, its timing can be flexible.

“Where manure is applied for P or K maintenance, its total phosphate or potash content should be used to adjust the fertiliser recommendation. Only use the available contents where indices are lower than target or the crop, for example potatoes, is especially responsive.

“In most situations, the old workhorses triple-superphosphate (TSP) and muriate of potash are good sources. When looking at other sources, high water-solubility will mean good availability, but low water-solubility doesn’t necessarily mean low availability. Basic slag used to be a successful source of phosphate for many years, but had zero water-solubility.”

British Survey of Fertiliser Practice (BSFP) figures.