British dairy market isolated from volatile world markets

The United Dairy Farmers (UDF) monthly auction held in Northern Ireland on 23 October achieved an average price of 18.03 pence per litre (ppl), 7.07ppl lower than the September auction. But what does it mean for the rest of the UK? DairyCo’s Huw Thomas explains.

The UDF fall was primarily a reaction to weakening world commodity prices and will inevitably contribute to a further decline in farmgate prices in Northern Ireland, already down over 6ppl from the peak of 29.92ppl reached last October.

World dairy commodity prices have been declining rapidly since the beginning of the summer, with prices now significantly below the levels reached last year. For example, whole milk powder (WMP) has fallen on the global market from $5100/tonne in August 2007 to $2850/tonne in October 2008. A weakening global economy reducing demand, increased milk production and higher stock levels have all exerted downward pressure on dairy commodity prices.

In continental Europe the situation is similar. With the absence of export refunds pushing market prices for both butter and skimmed milk powder (SMP) close to world price levels and, with intervention not open until March, prices for the coming months will be primarily governed by changes in the global markets. In pence per litre terms, it is estimated the returns from putting raw milk into the production of butter and SMP on both the world and continental EU markets is equivalent to between 18 and 19p/litre in October – similar to the latest UDF auction price.

Recently, the British dairy market has to some extent been isolated from the volatility of the world markets. This isolation is partly due to recent low levels of milk production combined with the dominance of the liquid milk market in GB, which is the destination for almost half of domestic raw milk production. Both of these factors mean there is very little ‘spare’ milk available at this time of year to be processed into products for export.

In addition, the relative competiveness of the commodity products that we do produce has been helped by the weakening of Sterling over recent months. Looking at the period since a number of dairy commodity products reached their peak in August 2007, Sterling has devalued by 21% against the Dollar and 15% against the Euro. This has acted as a significant buffer against the falling world and continental EU commodity markets.

However, with much of the rest of Europe more exposed to world commodity prices than GB, it is possible that imports will begin to undercut domestic prices for the more generic products such as budget mild cheddar, even when allowing for currency movements. This would ultimately lead to downward pressure on British farmgate prices.

This fall in farmgate price is likely to be mitigated, at least in part, by retailers’ continued commitment to their dedicated supply groups and the cost tracker payments associated with a number of these groups. These groups offer retailers security of supply alongside added value in the consumer-focused issues of animal welfare and environmental impact. However, with a number of retailers experiencing increased competition from discounters such as Aldi and Lidl, it remains to be seen whether consumers, and in turn retailers, will be prepared to pay more for this added value.

The structure of the GB supply chain helps to smooth out the peaks and troughs in prices seen elsewhere in Europe. Liquid milk accounts for 50% of the milk produced and cheese a further 30%, with much of this being sold to large retailers through ongoing contracts. The price fixing periods of these contracts was one of the main reasons why farmgate prices did not rise as rapidly as the commodity markets last autumn.

If the power balance in the market is equal, and the market is working efficiently, we should now see these price fixing periods protect our processors from rapid falls in the prices they receive for their products – at least for the time being – which will in turn protect the British farmgate price. These price fixing periods may also partly explain why we haven’t seen falls in the retail prices of dairy products, as retailers maintain their margins while they are paying relatively higher prices for the products they sell.

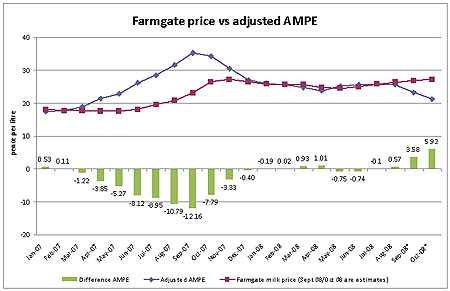

The partial isolation of the GB market, combined with the influence of direct supply relationships with supermarkets, can already be seen when looking at the difference between the average farmgate price and the market indicator Actual Milk Price Equivalent (AMPE) – which measures a processor’s return for processing raw milk into butter and SMP (adjusted for transportation costs).

Having experienced a significant divergence when the commodity markets rose in 2007 it now appears that (with estimated prices for September and October) the two measures are diverging again, with this time the farmgate price being above AMPE which indicates that some of the estimated £575m lost by farmers during 2007 due to this lag – as highlighted in the latest edition of DairyCo’s Dairy Supply Chain Margins – is now beginning to be returned (see graph below).

In the longer term the global dairy markets could easily turn again if supply or demand sentiment turns. It is evident that British farmers will face greater volatility in the future but we still have a large number of successful dairy farmers keen to drive their businesses forward. For these businesses, efficiency and the ability to manage this volatility will be the keys to success on the global stage.