On-farm data capture project a environmental ‘game changer’

© Bluesky International

© Bluesky International British agriculture’s environmental performance is frequently exposed to damaging criticism and misinformation.

But the AHDB Environmental Baselining project has set out to change that.

It aims to provide the industry with accurate information to counter its critics and to enable farmers to take a data-led approach towards a more sustainable future.

See also: How a data-led approach can manage sub-field costs

Why the project was set up

The project, supported by Quality Meat Scotland, was launched in the early summer of 2024. AHDB environment director Chris Gooderham explains why it was set up.

“Agriculture is facing a challenge to explain that farming systems can have a beneficial impact on the environment.”

According to the 2025 Climate Change Committee report, farming contributes a significant 11% of the UK’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

This figure is frequently highlighted by anti-farming campaigners and has affected public opinion, particularly towards meat and dairy products.

“But consistently overlooked is the fact that agriculture, unlike other sectors, has the capacity to capture, manage and store carbon,” says Chris.

“Countering the criticisms, though, is a difficult task due to a lack of accurate on-farm data,” he says.

That lack of baseline environmental data is also making it harder for individual farmers to transition towards new markets and more sustainable management practices.

Without a baseline there’s no way of gauging progress and less incentive to make improvements, says Chris.

“We hope to set that straight with the baselining project, which will equip individual farmers with the detailed data they need,” he adds.

Emissions and carbon

The project aims to gain accurate data on inputs, outputs, emissions and the scale and potential capacity of carbon storage on UK farms.

With this baseline established, the detailed data will then guide decision making to help farm businesses meet net-zero targets by 2050.

But, Chris stresses, the pilot project goes beyond those overarching aims.

Underpinned by accurate on-farm data and evidence, the project will provide a detailed insight into how British agriculture affects the environment.

It will also be looking at farming’s role in boosting biodiversity and controlling pollution, he says.

“By adding reliable fact to the often one-sided debate about British farming, the project will help to ensure farmers are recognised for delivering both food and environmental goods,” says Chris.

“We hope this will bring the industry together, empower farmers to drive change and forge a fairer, more sustainable path towards net zero 2050.

“A big outcome we hope to see is a behavioural change, with the extra information helping farmers to make better decisions that lead to improved output on the participating farms.”

Setup

The project was launched at the start of summer 2024 and has since attracted more than 500 applicants.

Of the 509 that applied, 322 grew cereals and oilseeds, 296 produced beef, 245 lamb, 149 dairy and 39 pork.

All were subjected to the same rigorous selection process.

“We were very pleased with the number and cross-section of farm types and scales that came forward.

“It gave us great scope to ensure we could select the ideal farms,” says Chris.

The final 170 were chosen because they covered a range of sectors: production systems, land management uses and practices, mixed farms and soil types.

As well as committing to taking part for the whole five years of the trial, the farms also had to implement an action plan to drive improvements.

In return, they are provided with fully funded carbon audits, landscape carbon measurements, run-off risk maps and soil carbon and nutrient analysis.

They are also supported by an approved adviser and have access to secure data storage and anonymised data analysis.

Progress

Three phases of measurement and recording will take place during the project – light detection and ranging (Lidar) scanning, soil sampling and on-farm audits.

These phases will establish the amount of carbon stored in soil, hedges and trees across the entire range of different land uses across all 170 farms.

GHG emissions and carbon sequestration will also be assessed.

What is Lidar scanning?

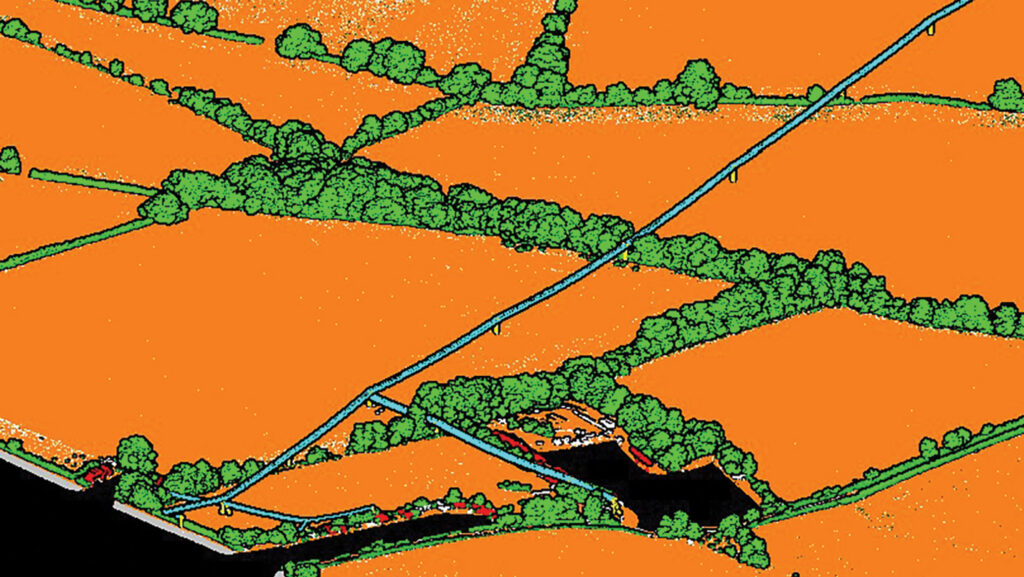

Light detection and ranging (Lidar) is a remote sensing technology that uses the light from a laser to collect measurements.

These are used to create highly detailed 3D images of objects and maps that are more accurate and revealing than satellite scans.

Lidar scanning

© Bluesky International

The first set of measurements were taken during a four-month period that began in December 2024.

The scanning was carried out by aerial survey specialists Bluesky International using drone- or aeroplane-mounted Lidar equipment.

All but two of the 170 farms were surveyed – the remaining two will be scanned this winter.

Collation, interpretation and presentation of the scanning data is being carried out by Trinity AgTech.

Dr Joe Oyesiku-Blakemore, a senior sustainability manager for Trinity AgTech, says Lidar uses a laser to measure the height of both the terrain and any above-ground features, such as hedges and trees, and that it is unparalleled in accuracy and resolution to any other airborne methods.

He adds that Lidar produces 1,000 data points per square metre and each one has a co-ordinate value and height, and that winter months are chosen because the laser penetrates better through sparse foliage.

Software algorithms then interpret the millions of points captured to build a 3D model for each farm.

The interactive image identifies specific objects such as buildings, field boundaries and woody biomass – giving precise heights, widths and densities of vegetation.

When combined with information drawn from satellite imaging and species identification, the software can calculate the amount of carbon stored across the farm.

It can also highlight which areas are the key carbon stores.

Water flows

While Lidar scanning is used to establish above-ground carbon stocks, it also allows ground features and terrain to be mapped.

“This is important because in addition to assessing carbon stocks, the Lidar system can highlight issues like water flows across individual fields,” explains Joe.

When combined with data on vegetation, the terrain maps will point to higher run-off areas and guide management decisions on drainage plans or nutrient planning to cut pollution risks.

The surveys also have potential benefits for wildlife.

Areas can be more easily identified where gaps in hedgerows, scrub or tree cover could be connected to create wildlife corridors and larger habitats, greatly enhancing their value.

“Detailed results will be presented in PDF or web-based format.

3D images

“The 3D images provided will give the farmer or grower a new angle from which they can view their farm,” says Joe.

A number of tabbed viewpoints will show different sets of features, such as hedgerows and trees, and display the calculated carbon store.

A further benefit of the scanning is that it highlights the extent and types of a farm’s natural capital assets, helping to demystify this area of the Transition process.

Results will likely be presented this autumn, with Trinity AgTech presenting the findings to the baselining farmers.

Early indications already point to a higher-than-expected level of non-farmed areas on holdings, with scrub, trees, banks or other vegetation.

These previously unaccounted areas could be acting as valuable extra carbon stores and wildlife habitats.

Soil sampling

Meanwhile, the second phase of testing is now under way with soil carbon and nutrient sampling being carried out by Agricarbon, explains Chris. This phase will continue until late autumn 2025.

Samples will be taken using vehicle-mounted core samplers down to bedrock. In less accessible areas such as woodland, marshes and dense vegetation, hand corers will be used to depths of about 1m.

Nutrient sampling will be carried out around the cores and results mapped to allow further comparative samples to be taken from the same point later in the project.

The soil sampling is proving to be the most costly element of the project, accounting for about half of the total funding, says Chris.

But accurately identifying soil carbon stocks is hugely important.

Previous studies have shown that soil holds about four times as much carbon as the above-ground vegetation.

This suggests that while policy has focused on peat and trees in terms of carbon stocks and sequestration, soil could perhaps play a bigger role in future plans.

“If we could increase soil carbon by just 10% we would make a huge increase in the total amount of carbon stored,” says Chris.

“We are also assessing the potential roles of other types of remote sensing like satellite imagery in identifying soil carbon stocks.”

Audits

The third part of the measurement phase will focus on audits of the farm business to establish efficiency levels and emissions.

Starting this summer, auditors are set to visit the 170 farms to assess production factors and performance to arrive at a certificated carbon footprint.

Next steps

The aim is to reach a net carbon figure for each farm that will offer an insight into a national picture.

From there, the AHDB is hoping to extend the pilot to a project across a wider base of farmers and partners.

Further ahead, Chris hopes this initial pilot could pave the way for a national Lidar dataset and even greater collaborations across other baselining and benchmarking initiatives.

“A national rollout is a no-brainer because it would yield valuable information to feed into government farming policy decisions, support industry sustainability and counter greenwashing,” Chris concludes.

Transition Farmer: Eddie Andrew

Eddie Andrew © Our Cow Molly

The baselining project is possibly the most important work ever carried out by the AHDB on behalf of British dairy farmers, says Eddie, who works closely with the University of Sheffield on a number of farming and environmental projects.

Eddie is also a major supplier of milk to the university’s catering outlets which serve 30,000 students.

Over the past few years, Eddie has seen the market share for cow’s milk plummet by 50% at the university while sales of plant-based drinks have soared.

“Students’ demand information about the food they buy especially its environmental credentials; carbon emissions are foremost in their minds.

“I have had to compete with the slick campaigns of the plant-based brands but their sales teams can claim low carbon footprints and point to data for products to back them up.

“I have had no data to make claims about cows’ milk or counter the criticisms of the plant-based devotees – it’s been like competing with one hand tied behind my back.

“Students have argued for an environmental charge for coffee made with cows’ milk to offset emissions – It’s felt like we have just been getting whacked,” says Eddie.

Now, though, he sees the AHDB baselining project as an opportunity to fight back.

“The reason I signed up to take part is simply that I see this project as a breakthrough.

“With the data collated, analysed and published, we will be able to look carefully at what we do,” says Eddie.

“Any areas where we can improve will show up and we can act to improve our position.

“But I believe it will show how much carbon we are sequestering to balance out the emissions associated with dairy production.

“Once we start to get the baseline advice, we will see where we can improve on emissions and on our ability to capture and store carbon,” Eddie says.

Case study: Lucy Noad

Lucy Node © Emily Fleur

Dairy and beef farmer Lucy Noad reckons the AHDB baselining project is a game changer.

She runs a 200-head, autumn block-calving dairy herd that keeps all of its followers – some as replacements and the rest to finish as beef.

In total there are about 530 cattle on the farm.

Lucy underwent the stringent application process to join the project because she is keen to demonstrate the value of carbon sequestration and storage on British farms.

“There is far too great a focus on emissions – our critics have emissions tunnel vision,” says Lucy.

“To date there has been nothing that has allowed us to say with confidence how much carbon sequestration and storage there is on farms.

“Everything we are doing on farm to mitigate our impact on the environment – taking a holistic approach that looks at soil health and biodiversity – is going unnoticed,” she says.

At Woodhouse Farm, both the Lidar and soil sampling phases have been completed.

“I really appreciate that the AHDB has opted to use the most up-to-date techniques to give us a science-led approach.

“This will give us the robust data we need to go to our buyers, the government and the public to show them that what we are doing, works,” says Lucy.

“Over the five-year project, we can then take a data-led approach to implement changes that will have the biggest impact on our carbon footprint.”

Case study: Robert Meadley

Rob Meadley © Rob Meadley

Arable grower and Brown & Co consultant Rob Meadley is awaiting soil core sampling to be carried out at the 600-acre Grange Farm and has arranged the farm’s carbon audit after the Lidar scanning was completed last winter.

The forward-looking farm business has had a previous association with the AHDB as one of its Monitor Farms and has taken strides towards becoming net zero with fuel sourced from an AD plant powering some of its ventures.

“I am keenly interested in how farming can contribute to cutting the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions using new techniques to sequester and store carbon.

“When I saw the pilot baselining project was being developed I knew it would be a great opportunity to find out exactly where we stood with our emissions and our capacity to store carbon.”

The simple fact is baselining is vital, he says. Arable margins are extremely tight and the BPS payment is diminishing so the future will require new income streams.

Those are likely to come from private finance for natural assets and potentially carbon trading.

“We won’t attract investors if we can’t demonstrate exactly what we are doing now, measure our progress and establish where there is potential for carbon capture and storage,” he says.

In the near future, more conventional agricultural customers are also likely to prioritise those farms with proven environmental credentials, Rob suggests.

“The baselining project will give us credibility by providing us with robust, independent figures about what we are doing and what we can offer to customers and the country,” he says.