How to work with neighbours to sell farmland to developers

© David Burton/FLPA/imageBROKE/REX/Shutterstock

© David Burton/FLPA/imageBROKE/REX/Shutterstock If a developer approaches you about your land, chances are it will be approaching one or more of your neighbours too, as it is unlikely that the footprint of a property development will follow land ownership boundaries.

One of the early questions is how to protect against one landowner benefiting from high-value land uses (for example, the prime residential element), while another is lumbered with the low-value uses (for example, infrastructure and low-cost housing).

See also: Selling land to developers – what farmers need to know

These valuation disparities can lead to disputes between neighbours and within families and can delay the project, particularly if the first phase of development is conditional upon planning permission for the entire site. A difficult negotiation could even see a developer walk away from the project altogether.

Michael Bray

Senior associate, Burges Salmon

Working with other landowners to form one cohesive group can save time and costs, as well as ensuring a fair deal for all – and ultimately allow the project to proceed and benefit all landowners.

Working effectively with other landowners

Be open with your neighbours – ask them if they have also been in contact with a developer. If they have, find out if it is the same company and if they want to collaborate on the negotiations.

You can save a lot of time and money by employing one land agent and one solicitor in the early stages of the deal and by ensuring each individual’s tax planning minimises both the inheritance tax risk and capital gains tax liabilities on sale.

There are often many practical considerations, such as:

- Obtaining vacant possession on each landowner’s property

- Identifying any restrictive covenants, which could prevent development

- Determining the VAT status of the adjoining site – you may be able to opt to charge VAT on your land which will allow VAT recovery, for example on your own professional fees

- If any of the land is unregistered, make a voluntary application to register it at the Land Registry.

Think about your collective and individual liabilities, as well as the longevity of the agreement between you. Also give consideration to what should happen if one of you wants, or needs, to sell or transfer land and in particular, what you do if the developer goes bust during the process.

In some circumstances a parent company guarantee may be sufficient, or the development could be set up in such a way to enable the landowners to sell the partially completed development to another successive developer.

For this to work the planning application must be made in joint names and the landowners must be given intellectual property rights in all technical reports.

Establish an appropriate voting mechanism and – if things do fall apart – decide how to deal with a breach of agreement and what damages/compensation are due if the project is delayed or can no longer proceed.

Deciding on a fair agreement for all

Developing a fair agreement will allow all landowners involved to share the benefit of the upsides of the land deal.

The more complex solutions may work better from a tax planning perspective, provided they can be put in place. The main thing to remember is these arrangements need to be considered early because it is complicated and could easily take longer to arrange than the deal with the developer or promoter.

There are a number of ways to achieve this:

Gross area basis

The landowners agree that the price they each receive will be by reference to the value of the total site. Be aware that this approach is difficult where there are numerous owners and more than one buyer.

A “Jenkins v Brown” pooling arrangement

All the owners pool their land so that they each own a percentage of the whole site. It has complexities, for example the farming of the land pending development and how to unravel the pool if the development fails.

Cross options

If landowner A sells part of his/her land, the developer has to pay landowner B to release his/her option over the same land. This approach is not as tax efficient as Jenkins v Brown pooling for example, but it may be worth considering if speed of agreeing documentation and minimising professional fees is an important consideration.

Create a company

Create a company into which the land is added and the landowners take shares.

Dealing with the developer

As far as you can, make sure that the selected developer has a good reputation, is financially secure and sufficiently experienced to survive any market volatility during the project.

Be aware that some developers may seek to put options on several local sites in order to prevent competitive development and allow them to promote another site in priority to yours, often with no intention of developing your site at all.

Ask developers to disclose all their other current, local development sites and give a binding commitment not to seek to control interest from other developers.

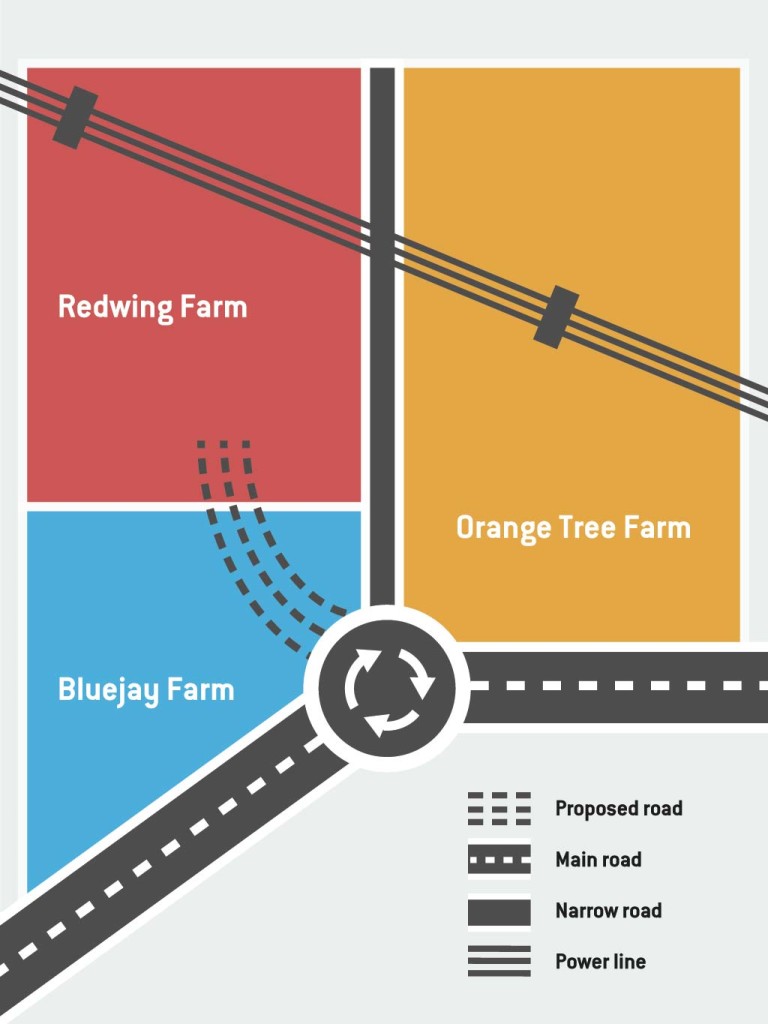

Development scenario – working together v working apart

In this fictitious scenario, Redwing Farm (red field) has plans to put forward this area of land for development. It is likely that Bluejay Farm (blue field) will need to permit a new access point to the roundabout on the main road because the access road to the red land is too narrow and will not have sufficient capacity to service a new housing development.

For the owner of Bluejay Farm, financial recompense could be a compensation payment, a purchase of the land required or he/she may want the land to be brought into the overall development.

The owner of Bluejay Farm may also negotiate hard on profit share if both his/her and Redwing Farm’s land are to be developed, because development cannot proceed without Bluejay’s agreement.

Orange Tree Farm (orange field) also comes into play for the owner of Redwing Farm to consider, because the overhead electricity cables will need to be put underground for development to happen.

While less necessary from a planning or legal perspective, if development is also proposed on Orange Tree Farm, the landowner may be prepared to enter into an agreement with Redwing Farm to appoint a joint contractor and to share costs.

This will minimise profit deductions resulting from their individual developers appointing different contractors and/or carrying out the undergrounding works at different times.

If Redwing Farm and Bluejay Farm act together

- Access to Redwing Farm from the main roundabout will be achievable, enabling the development and ultimate disposal of Redwing Farm

- Bluejay Farm could receive a windfall in being recompensed for the provision of access or even being joined into the overall development and taking a share of the profits

- For the owner of Redwing Farm, the owners of Bluejay Farm will be less likely to object to any planning application for the development of land belonging to Redwing Farm since the owners of Bluejay Farm will have a financial incentive not to stand in the way.

If Redwing Farm and Bluejay Farm do not act together

- Redwing Farm will need to consider another means of access, without which the development may not be able to proceed

- Bluejay Farm may be too small for a viable development on its own and so could miss out on the opportunity of making a profit from housing development

If Orange Tree Farm and Redwing Farm act together

- It is likely that the process of putting the overhead electric cables underground on both sites will be much quicker, cheaper and maximise profits

- Bringing Orange Tree Farm into the mix may also reduce the risk of the owner objecting to any planning application for the development of Redwing Farm, since they will also have an interest in its development to enable development on their own land

If Orange Tree Farm and Redwing do not act together

- The undergrounding of the cables by Redwing Farm will still be possible, but the process is likely to be much more expensive on a site-by-site basis.