What UK farmers could learn from small-scale overseas coffee producers

© Stuart Forster/REX/Shutterstock

© Stuart Forster/REX/Shutterstock British farmers could secure a better return from the marketplace by following the example of small-scale coffee producers overseas, Oxford Farming Conference delegates have been told.

Delivering the Frank Parkinson lecture at the conference, international coffee trader Konrad Brits suggested ethical and transparent trading practices could help to ensure more stable and fairer returns for UK growers and livestock producers.

Mr Brits, founder of Sussex-based Falcon Coffees, trades some US$95m (£77m) of coffee annually – buying about 24,000t of coffee beans from farmers in 18 countries, which is then sold and shipped to 400 customers in 23 countries around the world.

He said: “While coffee farming as a tropical crop is far away from British farming, there is relevance and perhaps lessons to share as we all face the growing tension of economic austerity and the pressure to constantly raise standards.”

See also: Coffee chains must back British dairy farmers

As in the UK, powerful supermarkets were seeking to drive down costs from their suppliers.

The unintended consequence was farmers were forced to engage in socially and environmentally damaging practices in a bid to absorb price pressures and keep their heads above water.

“There appears to be a strong disconnect between retail market forces and the real costs of ethical and sustainable farming,” Mr Brits told conference delegates on Wednesday (4 January).

True brew: The coffee-growing supply chain could hold lessons for British producers © Simon Brown/Falcon Coffees

This was easy to illustrate for smallholder farmers in developing countries – but harder to grasp in developed market economies where interest rates, debt structure, transport costs and exchange rates could make it difficult to compete with larger, better leveraged competitors.

Some 30 million smallholder farmers produced more than half the world’s coffee across 50 of the world’s poorest countries, said Mr Brits.

Furthermore, 21 of these countries featured in the bottom 30 of the World Bank’s list of countries by economic wealth.

This meant the global $100bn (£81bn) retail coffee industry relied entirely on an enormous number of people made vulnerable through a lack of personal security and poor food security – with little access to education, resources, credit and markets.

Konrad Brits believes many firms want to embrace ethics but remain focused purely on price © Billypix

Instability bad for farmers

Such an unstable supply chain was bad for farmers, bad for coffee companies and bad for consumers, said Mr Brits. Demand for coffee was growing, but the burning question being asked in the industry was: “Where will the raw material come from to feed this growth?”

“Altruism – the caring for the welfare of others, in this case smallholder coffee farmers – is not about philanthropy, not about social justice.

“It is about the bottom line. And the bottom line is the universal language that every single business speaks.

“We need to radically change the quality of life for millions of people if we are to secure the future of our industry and continue to prosper.

“Farmers need to live with dignity and the hope that farming offers a secure future for them and their families.”

Rather than driving down prices, Falcon Coffee worked with a sister company to improve the lives and economic prosperity of its farmers – creating a more secure supply chain in the process.

This included an agribusiness training programme focused on agronomy and financial literacy for smallholders.

The Rwanda Trading Company was working with about 60,000 coffee producers, said Mr Brits.

An initial pilot with 6,000 farmers had increased average yields by 155%, with household income from coffee up 61% in a year that the world price of coffee fell 15%.

“Where it really gets exciting is that, due to the increased export volume and profitability of Rwanda Trading Company, the initial costs related to the training programme were recovered by year three,” said Mr Brits.

“This is zero-cost sustainability.”

The programme has since been extended to 23,300 farmers across Rwanda and Tanzania, and is moving to western Uganda too.

“We are now trying to figure out how we could use low-cost technology to create efficiency in everything from data capture to payments and farmer training.”

Other initiatives included a non-profit World Coffee Research programme to breed climate change-resistant coffee varieties without genetic modification.

“These are great banners to fly and great stories to tell, but it is tough going,” said Mr Brits.

Embrace ethics

“Many companies profess to embrace ethics and sustainability, but are unwilling to make the initial investment or struggle to change their culture and remain focused purely on price. Some days I feel like Sisyphus pushing that rock up that hill only to see it roll back down.”

But Mr Brits added: “The winds of change are beginning to blow in our favour.

“We see a market coming towards us as more and more roasting companies adopt ethical sourcing standards and look to companies like ours to help them figure out credible sourcing policies that protect them legally, meet their clients’ demands, are cost-competitive and feed their brand equity.”

Traceability was the first building block in any successful ethical and sustainable sourcing initiative.

So too was an understanding that everyone in the supply chain needed to make a profit.

“When you connect your products to the people that produce them, you decommoditise that product.

“Its journey to you becomes a very human story. That influences its intrinsic value.

“This plays into the rising groundswell of community, local produce, local economies. People want to feel that the choices they make as consumers support ethical behaviour.

“This represents both a moral obligation and a marketing opportunity.”

Mr Brits said this was in stark contrast to his experience as a UK consumer.

Earlier this year, he had purchased food products from a major British food retailer, under a British farm label, thinking he was supporting British farmers.

He later found out the farm names were fictitious, nothing more than a marketing ploy.

“I was furious. Incensed. I still am. How dare they capitalise on my good intention as a global citizen, to do my small part, by duping me with fake brands, pitched right into that sweet spot of my conscience, for their own financial gain.

“The other piece of this profoundly morally corrupt behaviour is that they intentionally stop me from supporting you, pocketing the difference I trusted them to pass back to you. My response is that I will never give another penny to that company.”

With social media, these kinds of stories could go viral, doing untold damage to a brand, said Mr Brits.

Commercial suicide

The conversation around ethical sourcing and sustainability was not going to stop, it was only going to intensify.

“To avoid participating is to commit a form of delayed commercial suicide.”

Mr Brits dismissed any suggestion that the coffee community had “cracked the code” to sustainable coffee.

But there had been a change in culture – a move from a highly competitive buy-low, sell-high business model to one that was more nurturing.

British agriculture could learn from this he suggested – everyone would benefit from a sector which recognised the people behind the commodity and the need for everyone in the supply chain to be viable – socially, environmentally

and economically.

What’s already happening in the UK?

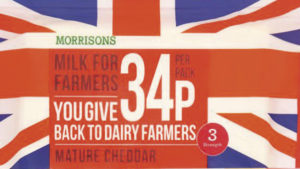

In October 2015, Morrisons became the first UK retailer to create a range where part of the retail price of the product_ goes directly back to farmers.

It was introduced during the farmgate milk price crisis after customers said they would like the opportunity to pay a little more for products to support UK farmers.

However, the scheme has proved sufficiently popular that the For Farmers range has been expanded so it now consists of milk, cream, cheese, butter and bacon.

Morrisons has injected vital cash back into the farming sector through its For Farmers range

Morrisons has committed to publishing sales information at regular intervals so customers can see how their purchases are helping to support farmers.

Figures released in December 2016 show since its introduction the range has generated an additional £5,818,269 of income for farmers.

While other supermarkets are yet to go down this path, they have sought to offer commitments over the sourcing of some of the products they sell.

For example, Booths Supermarkets rebranded all its conventional own-label milk as Fair Milk, guaranteeing its suppliers the highest price on the market to ensure they get a fair deal.