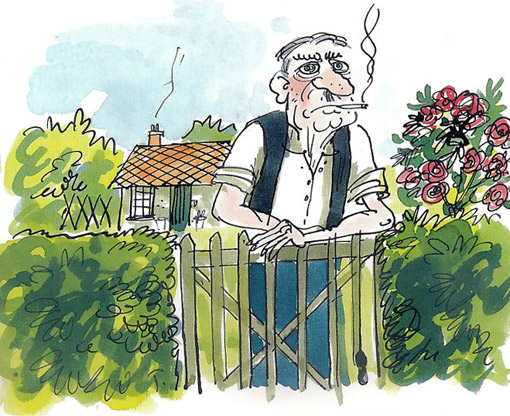

Farming Breeds: grandad – the good old boy

Join us for a funny, irreverent look at some of the characters that make the British countryside what it is. Our tongue-in-cheek guide puts characters such as the retired Major, the “perfect” next-door farmer and the young tearaway under the microscope. Here we meet Grandad – the good old boy, always happy to dispense his own brand of home-spun wisdom…

Grandad’s age is a mystery. It’s been “just turned 70” for the past 20 years. Not that he tells people that. His standard response to anyone who asks is: “Mind your own bloody business.” Adding, if they’re under 50: “You cheeky whippersnapper.”

His name’s a mystery, too. To his relatives, he’s just Grandad. His friends, however, call him Jack, the neighbours call him John and his God-given name – revealed, last Christmas, by his sherry-fuelled niece – is Albert. Mrs Weston, the sub-postmistress, occasionally refers to him as “Big Boy”.

But Grandad isn’t big. Not any more. He’s thin and wiry just like his Jack Russell, Chip, which can be constantly found at his feet. Quite a contrast, really, to the 16-stone hunk of a man who used to toss hay bales above head-height with such ease. Quite a contrast to the man who, with skilled and sensuous hands, used to work horses for 15 hours a day.

He doesn’t do much work on the farm nowadays. “I’ve been demoted to feeding the calves,” he complains. “Better speak to the boss,” he snaps when reps call. “Put your feet up, you deserve a rest,” his sons tell him.

He goes to market once a week and wanders around giving his opinion, whether it’s wanted or not. Usually it’s not. But he’s always right. The batch of cattle that he dubs “good uns” always end up making the most money. If he says it’s a “poor sort” then it always ends up with the worse conformation of the batch.

He goes to market once a week and wanders around giving his opinion, whether it’s wanted or not.

Quiet times see him touring dispersal sales, poking through piles of junk and spending a bob or two. Not that a pension goes far these days. “I would have liked to get it cheaper,” he says of his latest acquisition, a £1 spanner.

Most of Grandad’s sentences start with either “In my day” or “When I were a lad” and end in a tirade against computers. “What these youngsters need is common sense not computers.” Computers, he points out, won’t hoe sugar beet.

Other pet hates include television, anyone with a college education and Europe. All of it – but especially Germany. Grandad remembers rations, you see. He also remembers Winston Churchill. And, while he can’t remember any of his relations’ names, he can remember the names and dates of birth of six generations of pedigree stock.

Grandad lives in the bungalow out the back of the farmhouse. He lives on bread and cheese in the summer, soup in the winter – occasionally even unsticking the roll-your-own fag from his lower lip when consuming it. He slurps his soup noisily past his one remaining tooth which sits defiantly in the middle of his mouth like a cricket stump.

Grandad gets up at 4am. “It’s years since I’ve had a decent night’s sleep,” he complains to the feed rep, seemingly oblivious to the fact that, if you added together all the time he spends napping in the day, that alone would total six hours.

“Mustn’t grumble,” he says to the rep. Then adds: “You better speak to the boss about this load – I’ve been demoted to feeding the calves.”