Farming Breeds: Jim – the fledgling computer user

Join us for a funny, irreverent look at some of the characters that make the British countryside what it is. Our tongue-in-cheek guide puts characters such as the retired Major, the “perfect” next-door farmer and the young tearaway under the microscope. Here we meet Jim, the fledging computer user, who vows not to be beaten by the machine.

Jim didn’t want a computer. When he hears someone say software, it’s moleskin trousers he thinks of. A mouse is something he tries to keep out of the grain shed. The hard drive, as far as he’s concerned, is what the tractor is parked on. Jim hasn’t really got his head around the information technology revolution.

It was his son, Andrew, who badgered him into getting a home computer. “I can use it for my coursework when I’m home during the holidays,” he said. And that was the most convincing argument Jim had heard for getting a computer to date.

But Andrew’s been home on holiday from agricultural college for a week now and he hasn’t done much coursework on it. Not unless coursework involves looking at this Bookface thing (“it’s called Facebook, Dad,” his son corrects him), listening to music and playing a car simulator game).

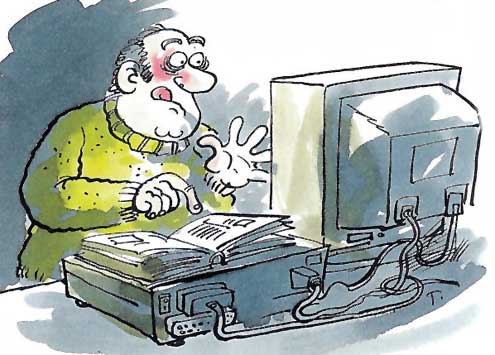

When the computer’s switched on, the study becomes a whirr of noise. Red and green dials flicker. Jim’s been avoiding this room. He looked in tentatively and saw an intimidating tangle of cables and lights. There’s well over a grand’s worth of computer kit in here. He thinks about the stock or machinery he could have bought with that money.

“If we’re spending that money on anything else, it’ll be a holiday,” his missus said. Jim looked horrified. That was the second most convincing argument he had heard for getting a computer to date.

One night, he does a web search for stud bulls and gets, well, let’s just say he gets a Dutch site that he wouldn’t have wanted his wife to see. He logged off immediately. Well, almost immediately.

Andrew, who’s marched Dad into the study for his first “lesson”, is using words like web, online and backup. “This bloody thing’s getting my back up,” says Jim, thinking about fixing that hole in the fence, about doing the sheep’s feet. He’d rather be mucking out than this. He’d rather be doing anything than this.

His son keeps talking about the version of Windows the machine uses – but the only window Jim’s interested in is the one he’s looking out of: out to the farm and the animals and the things he knows about. The things he’s good at.

He tries typing his name. His big, callused fingers hit six keys at once. The result is not Jim, but Gin. “How appropriate – that’s what I need right now,” he says.

Strange, really. Jim’s a man who understands, instinctively, the inner workings of a state-of-the-art combine. He can understand machinery – with no formal training and no guidance – almost without looking, like a surgeon understands the inside of the human body. Yet this thing. “I think it’s got me beat,” he confesses to the wife one night.

It’s just so so stupid. It doesn’t act logically. “Try turning it off then on again,” the man on the telephone helpdesk told him. “A computer’s only as good as the information you put in – put in rubbish and you get out rubbish,” the man had said. Jim told him what came out of his computer in no uncertain terms.

Before long, it becomes a battle of wills – man against machine. I’ll not be beaten by it, he vows one night. He sneaks into the study for a few minutes each day. He teaches himself to log on, load software, to use the worldwide web.

One night, he does a web search for stud bulls and gets, well, let’s just say he gets a Dutch site that he wouldn’t have wanted his wife to see. He logged off immediately. Well, almost immediately.

Soon he’s getting the hang of it. “I’ve been surfing,” he tells the cowman when he goes out for the afternoon milking.

The cowman tells him about a virus warning he heard about on the radio that morning. Jim, evidently still with a little to learn, rushes back to the farmhouse to make a doctor’s appointment.