Rural suicide – help is never far away

© Simon Skafar/Istockphoto

© Simon Skafar/Istockphoto Suicide remains one of the most difficult and painful issues facing rural communities, with those working in agriculture at significantly higher risk.

In the UK, men in farming are twice as likely to die by suicide as the national average, and in rural areas, the suicide rate rises to 12 per 100,000 people, the highest of any settlement type.

Behind each statistic is a family left grieving, a farm left struggling, and a community left asking questions that may never be answered.

See also: Long hours a factor in farmers’ worsening mental health

But you are not alone and there is support available (see box below).

The DPJ Foundation was created in 2016, after Pembrokeshire farmer Daniel Picton-Jones died by suicide.

In response, his wife Emma set up the charity to provide specialist help for rural communities – offering a confidential helpline, counselling, and mental health training.

Suicide is rarely the result of one single factor, explains charity manager Kate Miles, though there is often one extra thing that “breaks the camel’s back”.

“We want everyone to know how to deal with people who may be having suicidal thoughts,” she says.

Impact

The impact of suicide extends far beyond one person, touching the lives of many who care about them. Families, friends, and whole communities can feel the loss in deep and long-lasting ways.

“We often support families where there isn’t just one family member who has been affected,” Kate adds. “This is one of the reasons we do our work.”

Kate Scott, co-founder of The Rural Communities Mental Health Foundation, agrees that the impact of a suicide can be wide.

She lost her brother Robert in 2014 and describes this type of bereavement as “a deeply complex and personal journey, with all the ifs, buts, maybes and questions left unanswered.”

But amid the grief, silence, and complexity, there are moments of strength. “Tough times like these are when the support and togetherness of farming communities shine through,” says Kate.

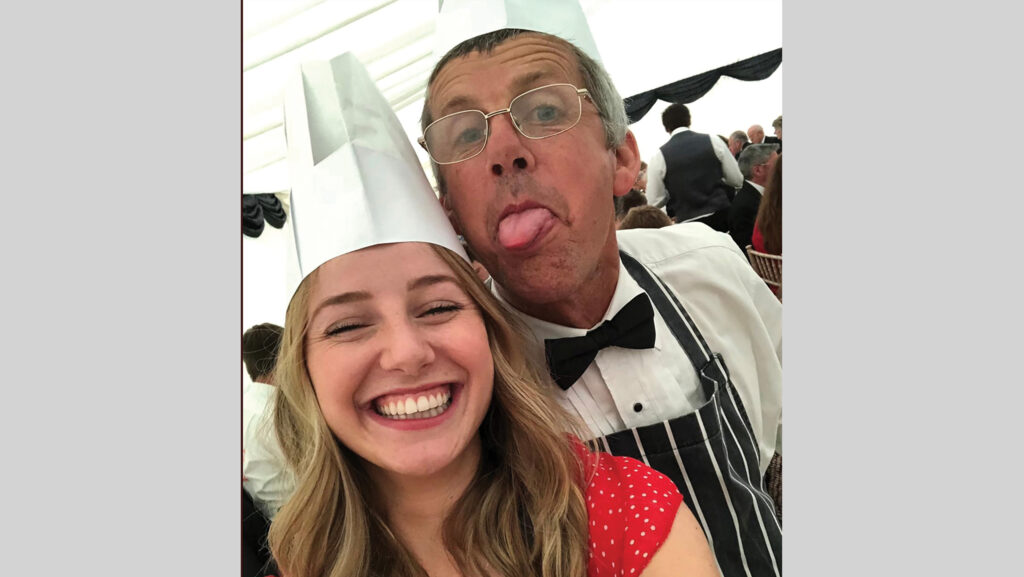

FW reader Sue Davies tells her own story

Sue Davies and her late father © Sue Davies

I’ve lost two men I love to suicide: my brother Stu and, two years later, my dad.

Both worked under the name Robert Davies Machinery – a family business in rural Shropshire, built by my parents, who worked hard and aimed high.

But ambition doesn’t protect you, pride doesn’t save you, and silence, as I’ve learned the hard way, can kill you.

In the UK, suicide is the biggest killer of men under 50. That’s our sons, dads, and brothers.

So, while you might read my story and think this is an isolated family tragedy, it isn’t. It is one part of a wider cultural crisis.

You see, we fear imperfection like it’s contagious, like if we sit too close to someone falling apart, we might unravel too.

So instead, we keep a safe distance. We polish the surface and hide the cracks, because it doesn’t fit the perfect life we’re chasing.

You know the one: Get married, have two kids, and a dog. Drive the Discovery, own the successful business, go shooting, keep smiling, never complain. A happy ending, right?

But what happens if you don’t tick the boxes? Or what if you tick them, and you’re still not okay?

What happens when your brother’s mental health is spiralling, and you feel like it doesn’t “fit” with the family brand?

When his struggle makes people uncomfortable? When he feels like an inconvenience?

Keeping up appearances

You see, Stu’s suicide broke something in all of us. And I think, in my dad, it broke something fundamental.

Because when your whole identity is built on keeping up appearances, grief exposes what you’ve spent a lifetime hiding.

It suddenly makes the respected, generous, and “successful” man, imperfect on a pedestal that’s in full view, and with it, a flood of excruciating loneliness.

Most people blame the physical isolation, long days, weather and debt pressures for high suicide rates in rural areas.

But I don’t think that’s it. I think it’s the emotional isolation. We’re surrounded by people, but starved of connection.

And the truth is, this isn’t a “them” issue. It’s a “you” issue, a “me” issue, an “us” issue.

Everyone in this community has a role to play. It’s not enough to just say “my door’s always open”.

We have to change the culture that makes people afraid to walk through it in the first place.

Being honest

Part of me feared writing this. I worried people would be offended, and would say I was too harsh, or too emotional.

But change doesn’t come from being liked. It comes from being honest. And my love for this community is exactly why I’m writing it.

Because this is the same community that left food on our doorstep when Stu and Dad died.

The one that lined the roads when we couldn’t have a public funeral during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The one that doesn’t fear ambition, but cheers it on and teaches you that nothing is too big if you’ve got the grit for it.

That kind of belief stays with you. And I want to give that same belief back, but this time, a softer one that says:

“You don’t have to be perfect, you’re not less worthy if you haven’t ticked the boxes, and you don’t have to smile if today feels too heavy.”

But you do have a responsibility to tell the truth, to check in, to listen, and to notice.

To be brave enough to be the first to speak up, not to shy away from pain, or choose comfort over honesty, surface over substance, image over intimacy.

Isolation isn’t overcome by perfection, but from the courage to be real, even when it’s uncomfortable, even when it means admitting you’re imperfect.

See, every time we reward perfection over honesty, we reinforce the lie. Every time we protect the picture instead of the person, we risk losing them.

I know you can’t stop someone from taking their own life. But we can help build a community where they don’t feel they have to.

Available support

- Samaritans Call 116 123 free, any time, day or night, or visit www.samaritans.org.

- You Are Not Alone Call 0300 323 0400 or email helpline@yanahelp.org

- The DPJ Foundation Call 0800 587 4262 or text 07860 048799

- Farming Community Network Call 03000 111 999 (open every day, 7am–11pm) or visit www.fcn.org.uk.