Meet the farmer who became a publican

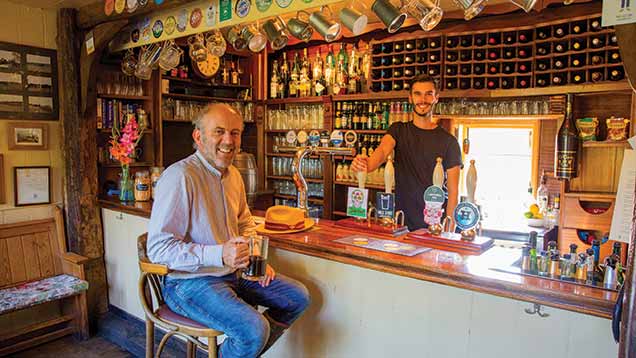

Stephen Carr samples one of the local brews with nephew Jonny Bunt. Photo: Craig Payn.

Stephen Carr samples one of the local brews with nephew Jonny Bunt. Photo: Craig Payn. The village pub is a special place. What would happen if a farmer bought one? Ask Stephen Carr, he did just that.

The Evening Standard published an article in 1946 called “The Moon Under Water”, in which George Orwell describes his view of the perfect pub.

He maintained any pub worthy of the name should have draught stout (never served in handleless glasses), open fires, cheap meals, a garden, motherly barmaids and absolutely no radio.

The pub had to be uncompromisingly Victorian with cast-iron fireplaces, a stuffed bull’s head over the mantelpiece, a ladies’ bar, and had to provide a good solid lunch of “a cut off the joint, two vegetables and boiled jam roll”.

The wistful quality of his tone hints that Orwell never found The Moon Under Water and, when it comes to pubs, we are a nation of Orwells, all with very definite ideas. Pub perfection as a concept probably doesn’t exist.

But if you buy a pub, as I did with my wife Fizz and my nephew Jonny 16 months ago, then you have no excuse not to do your very best to make it at least your own version of pub nirvana.

Top: Stephen’s mother, Aline Aspin, holding a terrier and, on her left, Stephen’s grandmother Phyllis Aspin and grandfather Fred Aspin. Bottom: Stephen’s mother and grandfather with a “thatched car”.

The Sussex Ox is the pub that my grandfather ran as a tenant of the Charrington brewery between the mid-1940s and the late 1960s and I spent a lot of my childhood there, playing foxes and geese with the farmworkers in the public bar and peeping through to the carpeted private area where the two local farmers sat and drank away a good part of their day.

It lies in a tiny village between Lewes and Eastbourne, a half mile from the main road, nestled in the rolling South Downs.

It is a spectacular spot, even in February when the southwesterlies blow the rain horizontally across the ploughed fields and the ditches gurgle with water.

But in May and June, when the hedges froth with cow parsley and the sun sets over one of the highest points of the South Downs – Firle Beacon to the west – it is a little paradise.

Last year we bought it freehold from a man with whom I played Saturday football and who happened to mention one day that he was selling up.

Jonny was running a pub in Bristol and expressed enthusiasm to head east to manage the Ox. We took possession a week before Easter.

The idea behind this radical farm diversification was that the farm would supply the pub (which lies at the very centre of our holding) with organic purebred Sussex beef and organic home-bred lamb from our Suffolk cross North Country Mule flock, slaughtered at our local abattoir and cut up by our local butcher.

We’ve also fattened about 12 of our own pigs over the past year which have been fed on our organic barley.

We decided to plant half a hectare of organic potatoes simply because we thought it might be fun and a good unique selling point for the pub. And because Fizz really likes potatoes.

We knew the potato yield would be low because we couldn’t irrigate and we couldn’t spray against pests or viruses, but we did supply the pub for six whole months with new and roasting spuds.

Bambino stored beautifully and seemed to morph from a lovely new potato to a tasty roaster. Arran Victory had a superb flavour but sprouted quickly. Golden Wonder was tasty and stored well, but the tubers emerged from the pub potato tumbler the size of large marbles. But primarily we grew the potatoes because we could.

Lots of pubs now take the provenance of their food – particularly their meat – very seriously, but very few have the luxury of their own farm, so we emphasise this connection in everything we do, not just the menu.

The flowers, grown by Fizz, might include barley in ear or some of the sunflowers or triticale that have appeared in last year’s potato patch.

Our 11-year-old daughter sells the eggs from her 18 hens on the bar. Magnificent pictures of Sussex cattle and their breeders, copied from the Sussex Cattle Society’s collection, are on the walls.

Stephen’s daughter with some of the goodies she sells in the pub as “Ted’s eggs”. Photo: Craig Payn.

And Fizz is about to undertake pre-booked tours of the farm (free with a reservation for lunch or dinner) so that people can meet our cattle and sheep in the flesh and see the journey from farm to fork.

Evolutionary change

We had spent long evenings both before and after we had signed on the dotted line debating how we could achieve the perfect pub.

Some of those initial thoughts were crazy dreams – a glass-walled extension with cows and calves at foot during the winter months (too expensive), or a “hay bar” tie-up area for riders and their horses (uninsurable).

But we realised early on that change would have to be evolutionary, not revolutionary.

When you buy a village pub, you are buying something that every local feels they own a little of. So the fear of change when one passes to a new owner is very real.

The only changes we made the first week were to ask the staff to abandon the uniform logo-bearing bottle-green polo shirts they’d worn before and wear their own clothes (Fizz’s school uniform had been bottle green and she simply couldn’t cope), and to put the home-produced beef and lamb on the menu.

Other changes were made much more slowly. We decided to freshen up the interior, but a few people expressed dismay that the hallowed nicotine-stained ceiling might go, so we found an exact colour match and, having sugar-soaped the ceiling, repainted it.

Nobody seemed to notice. After a few months we dared to knock a hole in a wall and extend the bar.

Fizz spent the summer making linen and velvet patchwork curtains for all the rooms and these went up window by window.

We have reduced the size of the menu and concentrated on our farm’s produce and local strengths such as Beachy Head-caught crab and lobster.

But certain things cannot and mustn’t change in a village pub.

The pub must be there as a welcoming refuge, whether it’s for a relaxing pint after work on a Friday evening, or for dry sherry on a Wednesday afternoon after an emotional village funeral, or for sparkling prosecco the night before a wedding.

It must know when the A-level results are out and whose children will be over the moon or locked in their bedrooms. It must be ready to absorb and then redistribute just the right level of village information. It must make you feel the world is now a better place because you’ve walked in.

Stephen (right) with Georgia Robbins (holding Howard), Jonny Bunt (holding Lyla), Ted Carr (holding Peter pug) and Stephen’s wife, Fizz. Photo: Craig Payn.

Nod politely

It can be hard to be in the pub as its owner. I find it difficult to switch off and just relax without worrying whether the couple next to me are enjoying their puddings or whether if by sitting down I am denying a hungry family a needed (and profitable) table.

I’ve had to alter my behaviour – I try not to talk politics there and always nod politely at whatever views are expressed. This is particularly hard when bearing in mind that for 30 years, editors of several farming publications have encouraged me to express a firm view on topics I am writing about.

I’ve also come to the realisation that, unlike farms, pubs pay 20% VAT on their turnover, of which not one penny can be reclaimed. This is a shock to a farmer whose career has involved emptying the Exchequer’s coffers through subsidy claims. I suppose at last I’m doing my bit to refill them by paying this pernicious tax.

It is incredibly hard work, so balancing the pub and the farm is a constant struggle. But it’s a lifestyle choice and is more than compensated for by the people we have met and the community we have grown part of. And we have a new engagement with our own farming that seems more grassroots, more involving. It is much more fun to see people actually enjoying your beef than to load a lorry full of fat cattle onto a truck for an industrial meat processing plant in Cornwall.

So would Orwell have liked the Sussex Ox? Our fireplace is wooden, not cast-iron, our range of artisan beers is served in whatever-shaped glass you like, and no-one could describe our front-of-house staff as “matronly”. Someone likes it, though, as we’ve been shortlisted for the Sussex Food and Drink Awards. Did the nominator like the garden? Or the cut off the joint on a Sunday? Maybe it was the lack of radio? This winter we’ll serve jam roll.

Essential traits of a publican-farmer

Vision

Everyone has their own idea of the perfect farm and the perfect pub. To retain your sanity, you quickly have to develop an ability to nod politely at any helpful advice offered (whether solicited or not), but nonetheless stick to the original game plan. Or, better still, convince yourself that the original game plan contained the new and very good advice.

Blind optimism

Like farms, pubs are in long-term

decline, with thousands closing in the UK each year, so you must be foolish enough to think it a good idea to set out to beat the odds.

A thrill from risk-taking

So many things about both jobs are beyond the practitioner’s control. Whether it’s the weather or government legislation, you have to roll with the punches.

Laziness

Otherwise know as a willingness to delegate vital tasks to others and trust in their honesty.

Modesty

Both enterprises require an enormous range of different aptitudes to run well. Accept the limits of your own abilities and let others who are much more qualified get on with the job.