Sculptor’s work inspired by farm animals

Sculptor Nick Bibby, well-known for his work with farm animals, explains where his inspiration comes from.

Q Which farm animals do you create?

Cattle, horses, pigs, sheep and poultry. I haven’t sculpted a goat, goose or donkey yet, but am not averse to the idea. I would like to sculpt more poultry. I tend to focus more on rare breeds.

Q Why are you interested in these animals?

I’ve always had a love of nature, animals and birds. I sculpt a lot of wildlife pieces, but nothing says “the British countryside” to me more than the sight of livestock out in the fields and meadows. Seeing the work of Herbert Haseltine, specifically his Champion Animals series, brought home to me just how much our familiar (and less familiar) breeds have changed in the 80 or 90 years since he sculpted them, both in form and in the drastic decline in numbers of many of our once-common ancient and traditional breeds. This sparked a desire to record and hopefully help raise awareness of those breeds – as well as some of our more common ones, because they too may be rare or even extinct in another 90 years.

Q What are the particular rewards/challenges of making them?

When I first conceived the idea to sculpt a collection of British champion animals, I naively assumed I would be sculpting a White Park, Highland or Suffolk, for example. It became obvious as soon as I started my first piece that it would not be generic examples of each breed, but loving portraits of characterful individuals that just happened to be of a specific breed. Portraiture is one of the most challenging forms of art because one is trying to capture the indefinable character and uniqueness of an individual, but it is also one of the most artistically rewarding (if one gets it right!) There is a unique bond between a champion animal and its owner or handler. Nothing beats showing them the completed sculpture and hearing them say, “That’s my ******. You’ve captured him/her perfectly!”

Q How do you work and capture the likeness?

I spend weeks or months completely immersed in the subject. Researching the breed (its characteristics, history and habits), visiting the subject, talking to its owners/handlers, watching how the animal stands and moves, absorbing as much information about it as I can, and most importantly, taking measurements and hundreds of photographs from every angle to take back to the studio.

Q What are your rural connections?

When I was growing up, we had several close family friends who were farmers, and the parents of my best friend at school had a smallholding where I spent a lot of time. Though my parents and grandparents were no longer farmers, my family history is in farming. At least eight generations of my father’s family, prior to my grandfather, were tenant farmers in West Yorkshire. I have always felt that connection.

Q Tell us a bit more about the actual process?

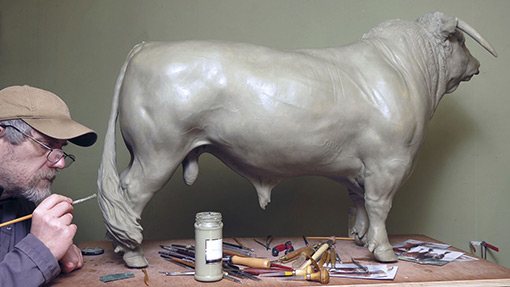

I almost never do working drawings for my sculptures, preferring to work directly from the three-dimensional image in my head. I spend a lot of time thinking about the piece and studying my reference photographs.

Sometimes I already know exactly how I want the piece to be. Other times, the sculpture slowly crystallizes in my mind as I study my photo reference and think about the subject.

I model in either clay (the sort found in art rooms all over the world) or oil-based wax modelling clay, depending on the subject, over a supporting armature of soft aluminium, copper wire and wood.

I always make my armature supports with a degree of flexibility, to allow for minor adjustments in pose as I work. It involves measuring and bending the wire to match the joint positions and bone lengths of the subject’s skeleton, then gradually adding the bulk and muscle masses of the form in clay or wax, before slowly refining and adding texture and detail.

Even with a highly textured subject such as a woolly ram (and though the viewer may not be consciously aware of it), the underlying anatomy still plays a vital role in determining the final form and surface.

Once the clay or wax sculpture is finished, I take it to the foundry to be moulded and cast into bronze.

From initial visit to finished clay or wax can take anything from a week to 15 months, depending on the size and complexity of the sculpture. “Sunshine and Piglets” – a quick sketch piece of a British Lop sow and piglets, done partly from life – took three days, while the approximately half life-size British Longhorn bull, Blackbrook Philosopher, took three months to sculpt.

When I’m in the studio, I generally work a 10- to 14-hour day, five or six days a week. Moulding and casting into bronze more than doubles the number of man-hours spent sculpting the original, to produce the finished bronze sculpture.

Q What’s the most ambitious piece you’ve ever undertaken?

In terms of size, sheer amount of effort, time and expense, the “Kodiak Brown Bear”, but I don’t really define “ambitious” in that sense. In terms of the artistic challenge, something like “Euston Malachite”, the Suffolk Punch stallion, “Apollo”, the heroic human torso study, or the face and folds of the bloodhound “Trailfinder Fortitude” were much more demanding.

Sculpting Eric – Highland Bull

Eric – Highland Bull

Euston Malachite

See also: Morpeth bull takes pride of place