What’s in a name? History of British field names revealed

© Adam Burton/Alamy Stock Photo

© Adam Burton/Alamy Stock Photo A historian has uncovered the hidden history of four British field names, tracing roots from Anglo-Saxon meadows to Roman villas and medieval execution sites.

Peter Wollweber, who recently earned an MA in History, spent part of his postgraduate research investigating the myths and histories embedded in field names across Britain.

See also: 15 weird and wonderful field names shared by farmers

Focusing his study on a working farm in Fife, Scotland, and guided by the family which owns it, he explored the origins and meanings behind common, but overlooked rural names.

His findings uncover the deep historical and cultural importance of naming traditions still visible in modern maps.

“Field names matter in 2025 because they’re an ever-present reminder of the enormous and varied role that independent farms play in shaping and preserving history,” says Peter.

The research centres on four distinctive names:

- Blacklands

- Gosmede

- Shamble Hatch

- Gaston.

Each conceals a specific story, with some stretching back more than a thousand years.

“Gaston will always be my favourite,” says Peter. “The landowners and I spoke about it for years and were none the wiser, until a professor who taught me as a student suddenly joined the dots.

“The remote location and the ancient boundary revealed a gallows site – and we realised there was centuries of history that had been forgotten except for its preservation in that single field name.”

1. Blacklands

At first glance, Blacklands might appear to be a straightforward reference to the colour of the soil.

“It is often used to mark boundaries, evolving for practical purposes so that farmers can distinguish between plots,” says Peter.

But deeper historical and archaeological research suggests a more significant connection.

Over the past few decades, sites named Blacklands have been consistently associated with Iron Age and Roman settlements.

Two such examples – Blacklands near Faversham, Kent, and another in Somerset – were both found to conceal Roman villa remains beneath the surface.

Why this link persists is not fully understood, but the prevailing theory lies in human behaviour.

“People tend to occupy the same sites generation after generation for the same reasons: access to water, fertile soil, strategic views or transport links,” Peter explains.

Over time, industrial or domestic activity, such as forges or household workshops, can discolour the earth, creating distinct dark patches that outlast the buildings themselves.

These patches would be easily recognisable and eventually passed down in local speech as “Blacklands”.

2. Gosmede

One of the oldest field names examined by Peter is Gosmede. Rooted in Old English, it combines gos, meaning “goose”, with mede, meaning “meadow”.

This practical naming style is typical of the Anglo-Saxon period, when fields and settlements were described based on their most obvious characteristics.

“You’ll notice that those names are, ultimately, simple,” Peter says.

“They describe, in the best Anglo-Saxon fashion, exactly what you could expect to find there.” Thousands of English place and field names retain Anglo-Saxon origins.

Even in London, names such as Paddington (“village of Padda’s people”) and Gunnersbury (“Gunnhildr’s burh”) show how Old English naming conventions persist.

In rural contexts, Gosmede is likely to have been known locally as a meadow where geese were kept, becoming a fixed label over time.

Before accurate maps, local people would trace the borders of land by walking and marking out visual or known features.

Gosmede would have served as a reliable identifier in a landscape where oral memory shaped territorial knowledge.

3. Shamble Hatch

At first glance, the name Shamble Hatch can seem unrecognisable to modern ears.

However, it finds a strong linguistic and historical connection to York’s famous Shambles – a street associated with butchers’ stalls in medieval times.

In this context, shamble refers to the tables or benches where meat was sold, while hatch likely relates to a gate or frame, possibly controlling access to the trading area.

“The name invokes the long farming tradition of seasonal markets,” explains Peter.

A field bearing the name Shamble Hatch would have been used periodically as a site of local commerce, likely for the sale of livestock or produce.

As these markets faded or moved, the name lingered, preserving a medieval memory that otherwise might have disappeared.

“Ironically, as the English language evolved, shambles took on new meanings,” he says. Its original reference to butchery was lost, and it became a synonym for disorder or chaos.

The result is that modern interpretations of names such as Shamble Hatch often miss their original connection to organised, regulated community events.

4. Gaston

The final and most haunting name in Peter’s study is Gaston, taken directly from the Fife farm he studied.

While versions of Gaston exist across Britain and may have multiple derivations, such as “settlement of the foreigners” or a “grassy place”, some evidence suggests a much darker past for particular locations.

“It’s very likely that the innocuous modern name once meant a place of execution at the edge of an ancient parish, since faded from memory and preserved only in the name of a field,” says Peter.

The theory stems from the medieval name Galliston, believed to mean “settlement by the gallows”.

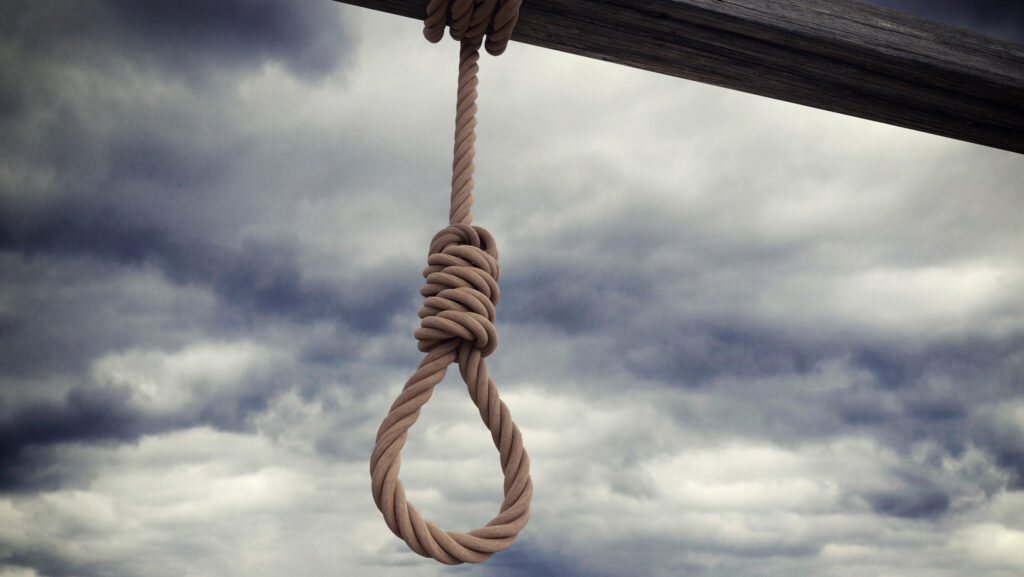

© Adobe Stock

In several instances, fields named Gaston are found at crossroads or at the remote fringes of old communities – sites that were often used for hangings or burials of those deemed outside the community, including suicides and criminals.

The belief that malevolent spirits could return to haunt the living led to the use of crossroads for such purposes, a practice seen across Europe and Asia.

From vampire superstitions in Romania to spirit-banishing rituals in Indonesia, the fear of the dead influenced the location of executions and unmarked graves.

Over time, the place names remained, even as their origins were obscured.

Cultural significance

Field names offer more than linguistic interest; they represent the continuity of Britain’s rural culture.

Each one reflects a moment in time, a local memory preserved in oral tradition and later cartography.

“Without them and the unique stories they safeguard, we would stand to lose far more than our food security,” says Peter Wollweber.

If you know of any unusual or historical field names, do send them to Farmers Weekly, we would love to hear them. Contact farmersweekly@markallengroup.com