Bluetongue a real threat to UK livestock

Bluetongue disease is just 60 miles away and presents a growing threat to the UK livestock industry, according to scientists.

Reports suggest that officials in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany cannot keep pace with new outbreaks, with Germany recording more than 100 cases a day.

In response to the quickening disease path, DEFRA have published a revised Bluetongue Disease Control Strategy, which includes rigorous measures to prevent the disease entering the UK and contain any outbreaks.

Protection zones of 150 km, as opposed to the 10km zones round foot and mouth cases, are among the strategies.

Government chief vet, Debby Reynolds, warned livestock producers that there is an increased risk of the disease spreading across the channel for the first time.

“The latest disease situation in Northern Europe highlights the importance of preparedness for this disease. It is important that producers are vigilant, alert to signs of the disease and that the report any suspicions to Animal Health immediately,” said Dr Reynolds.

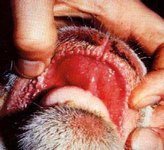

Symptoms include eye and nasal discharge, drooling as a result in the mouth, high body temperature and swelling of the mouth, head and neck (see below).

Spread by a species of biting midge, bluetongue emerged in Northern Europe for the first time during the summer months of 2006, fuelled by high temperatures and favourable wind direction.

Infected midges can spread large distances by wind, which suggests easterly winds could blow virus-carrying midges across the channel from continental Europe.

Furthermore, the re-emergence of the disease in Germany this year suggests the virus could have survived the winter, scientists suggest.

Although bluetongue does not affect humans, potential losses to the livestock industry are huge in terms of stock mortality, reduced productivity as well as loss of export revenue as livestock exports are banned from affected areas.

The risk to the UK is two fold, according to independent vet consultant, Tony Andrews.

“There are two routes by which bluetongue could enter the UK: Through imports of susceptible live animals to the UK from restricted areas and by prevailing winds spreading infected midges across the channel.”

“Initially, it was thought vectors would not be able to withstand the UK climate, however climate change could now allow them to survive. Not only this, but the climate is becoming more conducive for native species to establish themselves as vectors,” said Dr Andrews.

Clinical signs:

Sheep:

Eye and nasal discharges

Drooling

High body temperature

Swelling in mouth, head and neck

Lameness and wasting of muscles in hind legs

Haemorrages into or under skin

Inflammation of the coronary band

Respiratory problems

Fever

Lethargy

In cattle:

Nasal discharge

Swelling of head and neck

Conjunctivitis

Swelling inside and ulceration of the mouth

Swollen teats

Tiredness

Saliva drooling

Fever

Note: A blue tongue is rarely a clinical sign of infection

Nasal discharge, salivation and oedema of the muzzle

Redenning of the oral cavity and oedema of the mucous membranes

The feet of sheep with bluetongue are often affected with coronitis and laminitis causing lameness

(photographs courtesy of DEFRA)