Dairy software systems ‘holding back’ business progress

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Fragmented dairy herd data stored in multiple farm software packages are difficult to analyse and turn into actionable information, say experts, which is hampering farmers’ ability to progress their businesses.

Discussing the topic of collecting and sharing data, UK Dairy Day’s industry panel agreed that the amount of information recorded, duplication, and software systems that do not connect, are a headache for farmers.

See also: Data collection for dairy herds: What to consider

Data quality is also a problem, and there can often be gaps. Furthermore, the industry is frustrated that data streams still do not “talk to each other”.

In Denmark, dairy farmers had one data hub, said Dorset dairy farmer and Arla board member George Holmes.

By contrast, companies operating in the UK had invested heavily in their own systems and as a result, he said, they worried about losing value through collaboration.

“It is so important to get more of these programs talking to each other,” he added.

Software connections

Holstein UK’s group commercial director, Michael Halliwell, pointed out that there was so much data in different databases, yet the industry was still limited on how it could be shared, when it should be seamless.

Companies needed to invest in application programming interfaces (known as APIs, they connect two different computer programs), he said.

“Every company is at a different stage of development, some brands have no intention of developing API,” he said.

While some dairy farmers are “data savvy”, Michael revealed that others were “still writing things on a calendar”, and this variation affected how data was extracted off farm.

He wants to encourage a central platform for manufacturers of sensory tech – boluses, ear tags and collars – to upload their information.

© Tim Scrivener

“Sharing it across the whole farming platform – it’s a utopia we’d like to see, but it’s very challenging,” he admitted.

“Epigenetics is the unknown that has a huge effect, and we can’t quantify it, so sensor tech can gather data and crunch it.

“That would be a key development across the British industry – and the world.”

Volume of data

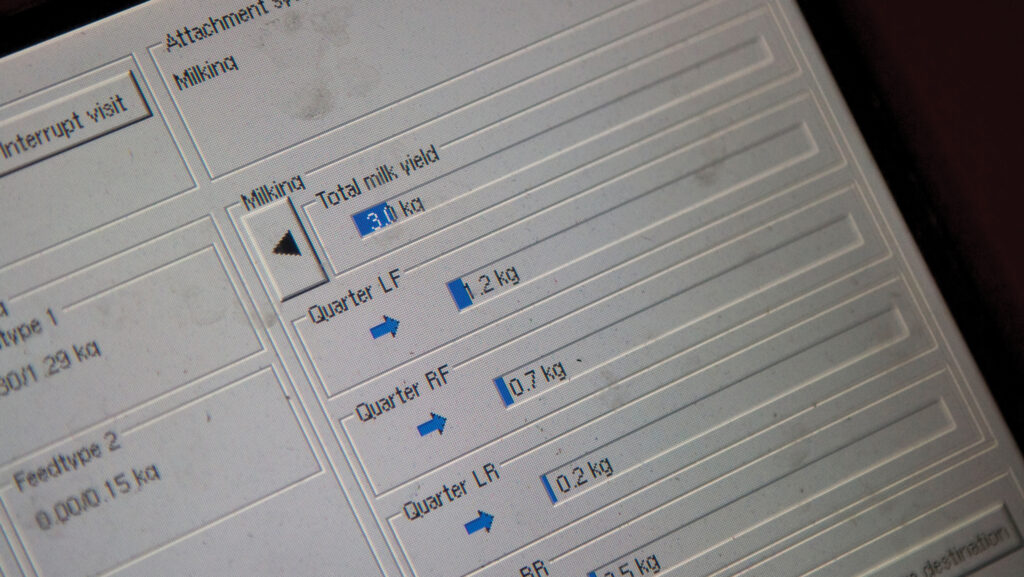

Revealing the sheer volume of information recorded on a daily basis, vet Michael Wilkinson, who works for Thomasson Farms in Cheshire, said that it takes three or four days a month to input data for four supermarket contracts covering the five farms.

The 5,000 cows plus 500 youngstock wear rumination collars, so information is collected every day.

Automatic calf feeding machines record every litre of milk drunk, and feed put out to 100 pens is also logged.

Michael uses these data to calculate KPIs for each unit and monitor youngstock growth rates.

Figures are used at staff meetings every six months, but most times data arrive too late to have an impact on management.

He said that there was too much information and not a lot of time to look at it.

“We are working with six to eight different companies to do things.

“We could spend hours looking at data and come up with nothing. We also spend time looking at the wrong data,” he said.

“We need to concentrate on what data is most important. We need a dashboard in the office that pulls it together with alerts, so we don’t have to go looking for [problems],” he said.

“I still haven’t seen a program that can do it – but it’s what we need in future.”

Duplication

Although he said that data were fundamentally important, vet Dan Humphries of Dairy Insight thought too much time was wasted because of duplication.

He did not think that the “right things” were being measured at the “right times” and said that farmers should first consider what they wanted to know.

“Decide what success looks like and what you are measuring. Understanding this helps you put data streams in place – a lot of it is waste.

The current approach is ‘to gather as much as I can and work out what to do with it later’,” he said.

Left to right: George Holmes, Arla; Michael Wilkinson, Thomasson Farms; Phil Halhead, Norbreck Genetics; Dan Humphries, Dairy Insight; Tom Hough, GroAgri; and Michael Halliwell, Holstein UK © Ruth Rees Photography

Benchmarking benefits

Dan suggested that analytical skills should also be transferred to the farmer, who will then be able to work on their own data to highlight problem areas, then call for specialist help.

This avoids hiring an expert who spends time (and the farmer’s money) analysing data and “finding nothing”, he said.

George agreed, saying he needed data-led decision-making.

Upskilling staff was also important, he said. He recommended benchmarking with other farms and said that doing so for his 1,000-cow unit had progressed the business.

“It is a more skilful job identifying in your own data what the problems are, so it is important to upskill staff.

“Benchmarking with other farms to identify where we are poorer has taken our farm forward to find out we are not competitive and why,” said George.

While Arla acknowledged the pressures of recording so many numbers and events, George said they tried to make forms easy to fill in and relevant for farmers “so they can understand it and use it to make changes such as using less artificial fertiliser by targeting slurry nutrients”.

“At home, we use it to make life easier and more efficient and improve stock longevity,” he explained.

Potential of artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence has the power to spot trends in data and is very good at predictions, but Dan thought it was still poor at “telling us why”, though this would change over time.

“It has massive [data] processing power,” he said, adding that the lag time between finding things out and dealing with them was now so short, it was helping to make real-time decisions, rather than working with information that was out of date.

George Holmes, Michael Halliwell, Michael Wilkinson and Dan Humphries were speaking at the 2025 UK Dairy Day, Telford, Shropshire