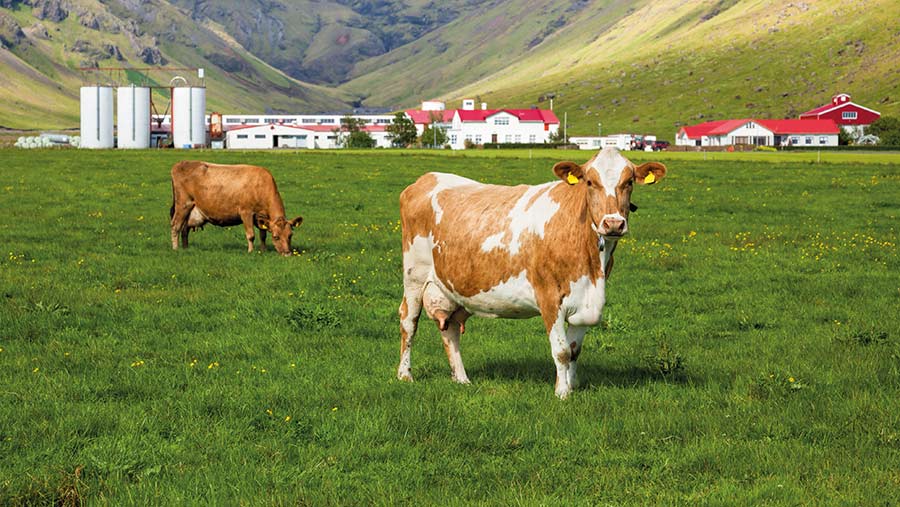

Why milking robots are a good fit for Iceland’s dairies

© Dmitry Naumov/Adobe Stock

© Dmitry Naumov/Adobe Stock About half of all dairy cows in Iceland are now milked through robots, with the fast-paced adoption of technology allowing farmers to enjoy a more laid-back way of life.

With electricity prices costing a small fraction of current UK prices, it is little wonder they have become a big attraction for farmers looking to plug a labour shortage.

One such person who has been captivated by the Icelandic way of life is Englishman and first-time farmer Jack Bradley, who hails from Burton-on-Trent.

See also: How Staffs dairy gets high robot visits with low cake costs

Jack Bradley © Rhian Price

He moved to Iceland in December 2019, after listing himself on a farming recruitment site, and hasn’t looked back since.

“I uploaded my CV and within five minutes I had a phone call from my [now] boss who asked if I would come to Iceland.”

The job was only meant to be for two weeks after Christmas, but this month marks his third year in the country working for Jónatan Magnússon.

Work-life balance

When he first arrived, Mr Bradley worked in Westfjords in north-west Iceland, just 20 miles from the Arctic Circle.

“I arrived and it was like a winter wonderland. There was 10ft of snow and everywhere was pure white – it was blinding.”

That lasted six months and was the worst winter he had experienced.

Mr Magnússon has since relocated to the Southland near Hvolsvöllur – a prime dairy area – where they are experiencing the mildest winter yet.

Jonatan Magnusson © MAG/Rhian Price

Buying a farm in Iceland is a lot cheaper than in the UK. Mr Magnússon purchased 180ha (445 acres) for £2.6m. This included 60 cows, farm equipment and machinery, so it was ready to farm immediately.

However, interest rates are nearly 9% and those on machinery are 11%, with building costs also much higher.

“To build a shed for 60 cows with a robot would be about £1m,” explains Mr Magnússon.

Despite this, expansion is under way, with the herd growing from 135 to 150 cows, which will make them the fourth-highest producer in the country.

Farm facts:

- Milking 135 cows, soon to be 150

- Cows will be milked through three DeLaval robots

- Farming 180ha (445 acres) growing grass and barley

- Milk sold to the farmer-owned co-operative, MS Dairies

- Cows on cubicles with rubber mats and hydrated lime

- Milk price of 88p/litre including subsidy

- Fourth-largest dairy farm in Iceland

Challenges

A typical day starts at about 7.30am. They check the cows have been milked, put the robots to wash, feed calves and are back in the house for breakfast by 9am – with little more to do out of silage season until 4pm.

But it is not all sunshine and roses.

“Everything here wants to kill you, even the sheep,” says Mr Bradley, who adds that the weather and Mother Nature can be brutal.

In December and January, daylight lasts for as little as four hours. This, alongside low temperatures that halt grass growth, necessitates cows being housed for long periods of the year.

Most cows are therefore housed year-round, but the government stipulates all dairy animals must be grazed for a minimum of eight weeks during the summer.

The fact cows spend most of the year indoors means cost of production is high.

However, herd sizes have remained small, at just 30 cows, thanks to a strong milk price of 88p/litre, and strict quota rules, which prevent any single farmer from owning more than 1.2% of the country’s total allocation.

But unlike in the UK, energy prices are cheap, at just 10p/kWh.

This is because the country is almost 100% self-sufficient in renewable energy, harnessing Iceland’s plentiful supply of natural resources such as wind, hydro-power, and geothermal energy.

Feed is one of the most expensive inputs. Nearly all farmers make baled silage to feed to cows, although Mr Bradley has introduced clamped silage, which dovetails well with the farm’s automated feeding system.

Grass mainly comprises timothy and ryegrass, which thrive in the volcanic soils. Despite the fact low winter temperatures halt growth, 24-hour sunlight during the summer months ensures high-quality silage for the long months ahead.

“We have extremely high sugar because of the 24/7 sunlight during the summer. In the west [Westfjords], my protein was about 19%.

Here we are getting 12% and I have never seen it so low, but the grass has been neglected,” says Mr Magnússon.

Breeding

The Icelandic cow is the only breed on the island. They are small, weighing in at about 450-550kg, with an average milk yield at 6,300 litres a cow across the country.

Most are polled and are of mixed colouring due to the fact colour has never been specifically selected. They originate from Scandinavia and contain some Jersey.

Live cattle imports are banned, with only Aberdeen Angus, Galloway and Limousin being imported through semen and embryos to widen the genetic pool.

As a result, disease levels are low, and the country is classified as TB-free and brucellosis-free.

All dairy cattle are artificially inseminated by an AI technician at a low cost of £10/cow to encourage farmers to continue using the service. However, there is much debate about the breed’s lack of genetic progress.

The industry voted on introducing another breed, but 70% of farmers said no because they don’t want the Icelandic cow to die out, explains Mr Magnússon. He says the breed is iconic with the public in Icelandic.

“We get high tariffs on imports, subsidies, and a high price for milk. Are we willing to sacrifice the goodwill of the people because we have a crappy cow?” questions Mr Magnússon.

Because of these strict rules, inbreeding remains a challenge and bulls are only used for one year, on average, to help control it. Farmers are now being subsidised to genetic-test their herd to fast-track genetic gain and prevent inbreeding.

“Genetic testing could be a huge leap forward, but there are still farmers who believe importing a new breed would be much easier,” adds Mr Magnússon.

Another challenge is that there is a shortage of vets, which makes dealing with sick animals more of a problem.

“We have to look online and do it ourselves,” says Mr Bradley, who is planning on doing a course in pregnancy diagnosis and a foot-trimming refresher to bridge the skills gap.

He doesn’t plan on returning to the UK and would like to own a farm in Iceland himself one day.