How to build a strategy to reduce sheep lameness

Last year Farmers Weekly launched its Stamp Out Lameness campaign to help the sheep industry meet recommendations to reduce lameness to 5% or less by 2016 and 2% or less by 2021.

A year on, Farmers Weekly, in association with MSD Animal Health, and supported by FAI Farms and the National Sheep Association, is continuing the campaign to help further drive the industry towards meeting these key targets.

Over the next four weeks, we’ll give you an insight into new thinking surrounding lameness and introduce The Stamp Out Lameness Hit Squad – experts who will visit three farms to give practical advice on controlling the problem.

Sheep lameness remains a significant challenge for the industry, having been placed on the government’s agenda in 2011 after the publication of the Opinion on Lameness in Sheep report from the Farm Animal Welfare Committee (FAWC).

This recommended:

- The prevalence of lameness should be reduced to 5% or less by March 2016 and to 2% or less by March 2021

- The government should enforce the law dealing with the welfare of sheep using various penalties

- The government should work with the industry to develop a national strategy to reduce lameness in sheep.

With three million sheep estimated to be lame in the UK at any one time, getting on top of the issue is crucial for an industry that prides itself on high animal welfare. What’s more, research carried out by Laura Green of Warwick University shows production losses due to lameness could be costing as much as £10-15 for every ewe put to the tup, with 8% lameness in the flock. That’s up to £15,000 for a 1,000-ewe flock.

Foot-rot and scald are most widely recognised as the two primary causes of sheep lameness, accounting for 90% of lameness. Both are infectious diseases, with scald a precursor to foot-rot.

However, it is likely contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) – another infectious disease – is prevalent on most farms, and is often misdiagnosed as foot-rot.

The primary difference between CODD and foot-rot is that the former infection starts at the coronary band, rather than in the inter-digital space. Little is understood about the disease, but The CODD Project at Liverpool University is looking at how it is spread and controlled.

As CODD is an infectious disease, many of the steps outlined by the five-point plan for controlling lameness can also help manage it, along with foot-rot and scald.

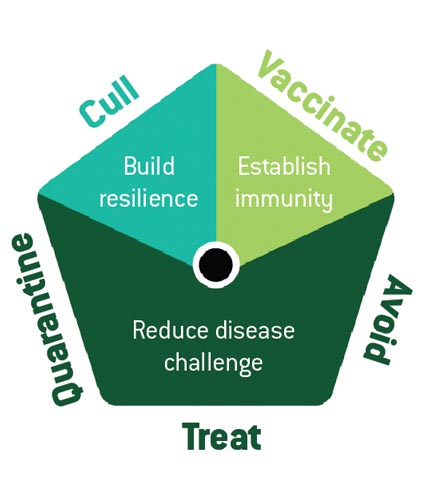

Formulated by Ruth Clements of FAI Farms, the five-point plan provides the industry with a practical and effective strategy to help meet lameness reduction targets. The campaign has already highlighted how farmers are benefiting from implementing the strategy, which includes:

- Culling badly or repeatedly infected animals

- Quarantining incoming animals

- Prompt treatment of clinical cases

- Avoiding spread at handling and gathering

- Vaccination.

The five-point plan will form the basis of recommendations outlined by the Stamp Out Lameness Hit Squad, which will comprise Ms Clements and vet Joseph Angell, who is undertaking a PhD on CODD at Liverpool University.

“Massive, substantial changes are achievable if you put the five-point plan in place,” says Ms Clements.

“In FAI Farm’s flock of 1,200 ewes we managed to drive lameness down from 18.5% to less than 2% in the first year.”

To get on top of the problem, farmers should first ask themselves what they are doing to protect each ewe from going lame, she says.

The areas outlined in the five-point plan are designed to address the three building blocks for controlling lameness: building resilience, reducing disease challenge and establishing immunity.

“There are three building blocks to nailing disease on farm: building resilience, reducing disease challenge and establishing immunity.” And all of these are addressed through the points laid out in the five-point plan.

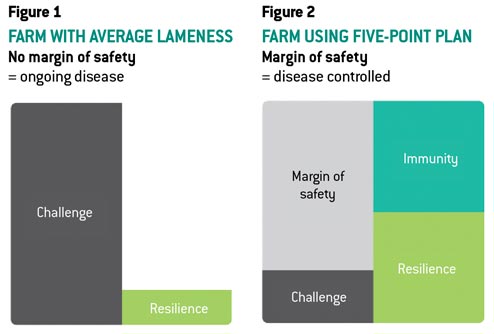

By adhering to these basic principles, farmers have the opportunity to create a “safety buffer” or “margin of error”, which will help protect their business during times of challenge. This means in times of stress, such as high rainfall or poor forage quality, sheep are less likely to succumb to lameness.

Building resilience

This is about looking at how you can help the flock gain additional levels of resilience to lameness.

There are individuals in a flock that will cope better with foot-rot and those that won’t.

Action: Culling sheep prone to lameness (point one in five-point plan).

Reducing disease challenge

Foot-rot, scald and CODD are all infectious diseases. Ask yourself how you can reduce the chance of disease spreading from sheep to sheep and avoid propagation of disease.

Actions: Quarantining, prompt treatment, avoiding spread (points two, three and four in five-point plan).

Building immunity

Natural immunity is limited so vaccinating against foot-rot, while using the other points in the plan, is a key tool in the fight against lameness.

Vaccination is about giving immunity at high-risk times, such as high stocking rates at housing or at pasture.

Action: Vaccination of stock (point five in five-point plan).

By following the basic principles of the five-point plan, producers can create a “safety buffer” or “margin of safety”, which means their flock is less likely to succumb to lameness in times of stress.

For example, on an average farm without the five-point plan in place (fig 1), the flock may have a certain level of resilience, but this is easily overcome when challenge increases. A low margin of safety means lameness will never get under control.

Ms Clements explains how many farms will witness seasonal fluctuations in lameness corresponding to challenges at certain times of the year.

“Lameness can often grumble along and then suddenly peak. This means as the challenge increases you’ve got a negative margin of safety, which can potentially lead to 10% or even 50% lameness.”

Recent variable weather and poor forage quality have been the tipping point for many farms who have not had a suitable margin of safety in place.

She says farmers don’t have to accept these seasonal peaks and troughs and should instead work to create a significant margin of safety.

On a farm with the five-point plan in place (fig 2), they have built resilience and immunity in the flock, while also reducing disease challenge. As a result, they have a significant margin for error. Should challenge increase, sheep are less likely to succumb to disease as there is a big safety buffer.

“If you can implement all of the five-point plan, you can increase your margin of safety within a year,” says Ms Clements.