Q&A: What is haemonchus and how to prevent and treat it

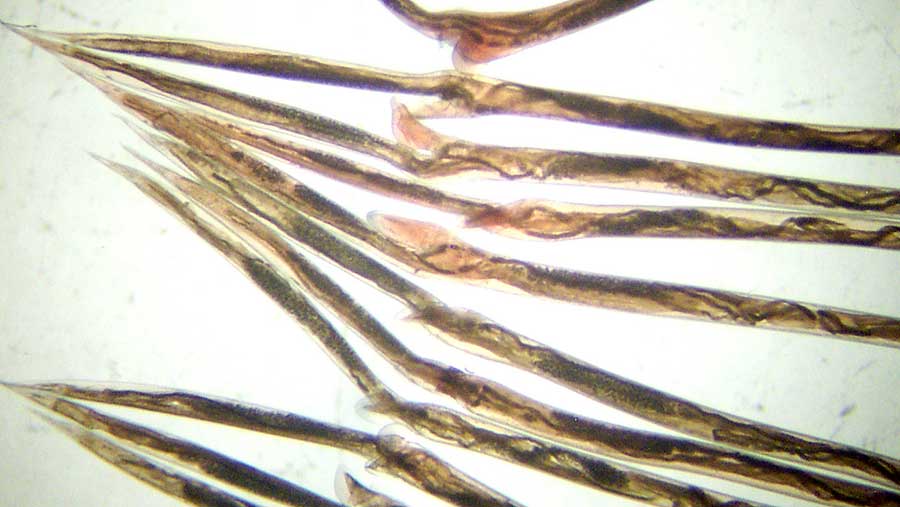

Haemonchus contortus barbers pole worm adult females © CSIRO/CC BY 3.0

Haemonchus contortus barbers pole worm adult females © CSIRO/CC BY 3.0 Good worm control plays a pivotal role in the success or failure of a sheep flock.

Get it wrong, and you could be left with stunted growth rates, gut damage and even death in some severe cases.

One of the most serious worms to be aware of is haemonchus – a blood-sucking gut parasite, which is estimated to affect about 56% of sheep flocks in the UK.

Below, vets from Synergy Health Centre, Dorset, discuss what causes the parasite, how to diagnose it and what to do if you suspect a case of haemonchus on your farm.

What is haemonchus?

Haemonchus contortus – sometimes known as barber’s pole worm – is a parasite that lives in the fourth stomach, the abomasum, of the host animal.

It affects stock by sucking large amounts of blood from the stomach, which can ultimately end in death if not treated.

Though mainly found in sheep, haemonchus worms can also infect cattle, goats, alpacas, llamas and deer.

What causes it?

The worms can be found in infected pasture or purchased livestock.

Haemonchus eggs thrive in warm, wet conditions, meaning that affected pasture can become particularly infectious in the run up to autumn.

Bought-in stock can be carriers, meaning they could infect previously clean pasture when brought on to farm, if not quarantined first.

What symptoms should I look out for?

Depending on the severity of the burden, clinical signs will vary.

However, where a heavy haemonchus burden is present, blood loss can be up to 1.5 litres/day, meaning it’s imperative to keep an eye out for the following symptoms:

- Lethargy

- Low or slow growth rates

- Weight loss

- Bottle jaw

- Anaemia

- In severe cases, sudden death.

How can I diagnose it?

Because haemonchus can be such a fast-acting parasite, sometimes the only way to diagnose a problem on farm is through postmortem of the dead animal, so it is crucial to submit fallen stock to your vet.

In less severe circumstances, faecal egg counts can assess the presence and severity of an infestation.

By analysing 10 random, individual dung samples from animals, vets can calculate an average worm count.

An adult worm can shed about 5,000 eggs, so the presence of haemonchus will often result in an extremely high egg count.

Using the Famacha (see below) test can also identify evidence of anaemia, which could also indicate a haemonchus issue.

Sheep are selected for treatment based on their level of anaemia, which is assessed through a colour chart.

Famacha scoring – what is it and how to do it?

Scoring stock based on the Famacha system allows producers to make decisions on worming treatment based on the level of anaemia due to haemonchus infections.

The colour-coded chart works by scoring animals from one to five (with a score of one meaning not anaemic and five signalling severe anaemia) based on the colour of their third eyelid.

“Using the scoring system means we are able to protect against any future resistance issues by only treating animals that really need it,” explains Emily Gascoigne, veterinary surgeon and sheep specialist at Synergy Farm Health.

“When animals fall into the score four or five categories, that’s when we need to be optimising treatment.”

What is the best way treat a case of haemonchus?

Despite the potential severity of haemonchus, the good news is that there is a wide range of treatments available.

While drenching all sheep may seem like a simple solution, this puts an intense selection pressure on the worms, which could result in anthelmintic resistance.

Therefore, treatment should be specific and targeted to avoid issues.

All classes of wormer can be used to target haemonchus, but resistance has been observed in multiple classes – globally and in the UK – so care needs to be taken.

The newer wormers, such as Zolvix and Startect, are important to use as part of quarantine control, and narrow spectrum treatments such as Closantel – more commonly used to treat fluke – can also form part of control.

Careful calibration of guns is important to avoid under and overdosing.

Is there anything I can do to prevent it?

Cold weather, particularly frost or snow, significantly reduces haemonchus eggs residing in pasture, which will help to prevent outbreaks.

However, moving stock off heavily infected ground is very important to minimise the spread of infection.

Buying in stock can increase the risk of bringing haemonchus on to farm, so quarantining purchased stock, drenching them before they join the main flock and conducting a faecal egg count two weeks later to check if the treatment was effective, can help to minimise this.

Aside from that, farmers should work with their vets to ensure a comprehensive parasite control plan is in place, which is reviewed every year.

The influence of the weather on haemonchus

Dr Hannah Rose Vineer, from the University of Liverpool, has been researching the effect of weather on haemonchus.

Below are some of the key findings to consider when planning worm control.

- Haemonchus eggs develop at temperatures above 9C

- From August to October, the infected egg development peaks due to the increasing temperatures – this also coincides with peak faecal egg counts

- In terms of speed, eggs develop faster at higher temperatures:

- At 10C,it takes about a month to develop from an egg to the infected stage

- At 15C, this decreases to about two weeks

- In very warm temperatures (+15C), this can decrease again to just a week

- This is worth considering when it comes to rotation planning. If your aim is to avoid infection, you may need to shorten the residence time of a paddock and move mobs of sheep on quicker in warmer conditions

- Infective larvae need moisture to move out of dung and on to grass, typically about 2mm of rainfall:

- Under normal summer conditions (warm with regular rainfall), larvae move regularly on to pasture from dung

- Pasture may suddenly become heavily contaminated in late summer when a dry period is followed by rain. When this happens, faecal egg counts may increase rapidly within three weeks of rainfall

- A large proportion of infective larvae are found in the soil, not on the grass, where they can be very long-lived. Larvae will move between the soil and grass dependent on weather conditions, moving down into the soil to escape adverse conditions, such as very dry, and very cold or hot periods.