Guide to CT scanning and how it can benefit your flock

Computed Tomography (CT) scanning is improving the national sheep flock, allowing breeders to select their best animals to breed from and providing commercial lamb producers with tups that deliver traits desirable to their flocks.

Costing from as little as £33 a head, thanks to subsidies from red meat levy bodies, this technology is affordable for every sheep farmer – but what does it involve and what are the advantages to flock productivity and profitability?

We joined farmers at a CT demonstration day led by Welsh red meat levy body Hybu Cig Cymru, and Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) to learn more.

See also: New guide for sheep farmers on using EBVs

Kirsty McLean and John Gordon head the CT scanning service for SRUC Research. They brought the institution’s high-tech mobile scanner to Aberystwyth University’s Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS) farm near Aberystwyth to scan over 170 ram lambs and demonstrate how it works.

1 The scan

Sheep in cradle © Debbie James

Sheep are mildly sedated before they are strapped into a purpose-built cradle on the scanning unit. The machine is no different to that used for medical imaging.

The animal passes through a circular gantry and low dosage X-rays are beamed around it while detectors measure the absorption of those rays.

A longitudinal scan of the whole body of the animal is initially taken and landmark lines are placed on this image at specific anatomical positions.

The animal is scanned in three places – the back of the pelvis, the 5th lumbar vertebrate and the 8th rib – “mapping” the three areas that are of particular interest for measuring commercial traits.

A full body scan is then taken, storing cross-sectional images every 8mm down the length of the body.

The scanning process, which measures the weight of muscle and fat across the whole carcass, takes less than three minutes.

Fat, muscle and bone appear on the scans in different shades of grey.

Measurements from these images enable accurate predictions of carcass tissue weights – in the case of fat 98%, muscle 96% and bone 89%.

2 The information CT provides

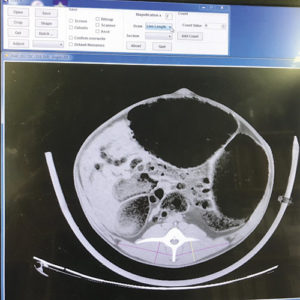

Scanning images © Debbie James

CT scan data predicts to an accuracy of 96-98% the carcass tissue weights and percentages in the animal, the killing out percentage, the muscle to bone ratio, the muscle to fat ratio, gigot shape and eye muscle area.

This data, which provides an overall potential measurement of meat yield, allows breeders and farmers to identify the very best sheep to breed from – those with the best genetics for growth rate and meat yield.

“Some farmers request specific, additional information, such as number of vertebrae, and we can provide this,’’ says Kirsty McLean.

The data for every animal scanned is sent to Signet for inclusion in the database.

The information is presented in a form that can be easily input into performance recording and genetic evaluation databases.

3 How the information can be used to influence breeding decisions

Breeders receive results and predictions for individual lambs as well as a breed average for the year.

“These data feed into the national genetic evaluations and estimated breeding values (EBVs) produced for CT lean, CT fat and CT muscularity, which allows breeders to compare sheep across a breed on their genetic merit for these traits.

“Higher EBVs indicate more lean or fat in the carcass, or a rounder shape of the gigot, at a fixed age.”

With desirable traits specific to every pedigree breeder and commercial lamb producer, the data provides the opportunity for a good match between tups and ewes.

“There might be a desire to increase shape at the back end, or to decrease fat levels. Breeders and farmers can look at the figures and choose a tup that is strong in those values, whether they want to dilute or increase a specific trait,’’ says Miss McLean.

“Ewes in a commercial flock are there because they are good mothers and produce good quantities of milk so farmers would be relying on the ram to produce the lamb carcass traits. The aim would be to choose a tup to complement the ewe type.”

That could be muscle shape, muscularity, muscle volume, bone density or internal fat.

Is CT scanning for me?

I am a pedigree breeder and sell tups and ewes. How would I benefit from using CT scanning?

CT data and images offer a valuable way to support the promotion of recorded rams at sales.

Breeders like to buy sheep that progress their own flocks and there is a growing interest in EBVs from commercial producers.

“Pedigree breeders can use the CT information to better tailor their rams to the commercial buyer’s flock,’’ says Mr Gordon.

I only sell store and fat lambs at market. Would there be a point to me CT scanning?

No, but it would be worth using rams that have been CT scanned to produce these lambs so you can identify sires that will leave lambs with better conformation and optimal fat levels.

“These lambs will achieve better grades at slaughter and will therefore be more valuable to finishers or abattoirs. These customers will then pay more money for these store or fat lambs and will buy from the producer again,’’ says Mr Gordon.

CT scanning – the benefits

Close up scan © Debbie James

Incorporating CT data into the evaluation of a flock greatly enhances the accuracy of Estimated Breeding Values (EBVs) for growth and carcass traits.

Indexes and EBVs are increased if the data demonstrates that an individual animal or family is genetically superior.

Elite lambs among homebred ram lambs can be identified and the data used to select stock sires.

CT is the only legitimate means of assessing gigot muscularity for Signet to evaluate and provides opportunities to measure new traits, such as loin length, vertebrae number and predictors of meat quality. EBVs for these traits are expected to be provided by Signet soon.

CT scanning – the facts

Scanning unit © Debbie James

Scanning in the SRUC mobile scanner costs £88 a lamb but farmers in Wales qualify for a 50% subsidy from HCC and in Scotland, from Quality Meat Scotland. In England, AHDB contributes £55 for each lamb scanned and some of the breed societies also contribute to the cost.

If sheep are taken to the scanner’s home base, at Bush Estate, near Edinburgh, the charge is just £60 and farmers still qualify for the subsidy.

The subsidy applies only to terminal sire breeds from recorded flocks – the service is used by the Texel, Charollais, Meatlinc, Suffolk, Beltex and Hampshire Down breeds.

Sheep are scanned at between 20 and 24 weeks of age. “When we did the calibration trial work on CT scanning we looked at three different ages and this age gave us the best results and is the most applicable to the industry,” explains Miss McLean.

Prior to scanning, Signet measures a lamb’s depth of back fat and muscle by ultrasound scanning. The scanning technician then provides the breeder with a list of the top 10-15% animals in the flock as possibilities for CT scanning.

Miss McLean recommends selecting at least five of these lambs to CT scan. “They need to be ones they are going to breed from or those that are going to be the most valuable to them,” she suggests.

“Sometimes breeders will also bring lambs they particularly like the look of, or if they know the history of that animal. A lot of pedigree breeders have small flocks so they will know every sheep individually.”

To qualify for the subsidy, farmers must not present fewer than five animals for scanning or more than 15. “Farmers will sometimes bring females along and pay the full amount because it is beneficial to their flock,” says Mr Gordon.

Case study

CT data is being put to good use by Cefin Pryce, who runs a flock of 40 pedigree Texel ewes at Yr Helyg, near the Powys town of Llanfair Caereinon.

Mr Pryce started performance recording five years ago but the accuracy of his flock was not as good as he had hoped.

“It takes a while to get the accuracy right. We have some individuals with good genetics but because they don’t have the performance data they are difficult to identify using EBVs,” says Mr Pryce. Because parents and grandparents in the flock are not recorded, the accuracies that are associated with the EBVs for those animals are low.

Three years ago, he CT scanned his flock for the first time and has since scanned 10 ram lambs a year.

Growth rate and the muscle-to-fat ratio are two of the traits he particularly focuses on.

“I would use those rams that come out on top as much as I can,” says Mr Pryce.

He is not expecting gains to be immediate. “It is going to take a bit of time but it gives us the opportunity to improve the genetics in our flock while maintaining type to produce the best animals we can.”

Mr Pryce is using the scanning results to increase the accuracy of his EBVs.