UK dairy farms benefiting from using genomics

Many farmers are reaping the benefits of using bull proofs, with faster improvements in genetic merit and herd performance.

Genomics gives an early and more accurate prediction of a young sire’s genetic potential than has been possible in the past, allowing bulls to be used at a much younger age, rather than waiting for them to be progeny tested.

It is calculated by extracting DNA from an animal’s hair follicle, for example. This is then analysed by a machine for a large number of genomic variations, known as SNPs, and compared against a UK-specific SNP-key, which translates the information into genetic indices.

It is estimated about one-quarter of UK dairy inseminations are from genomic young sires.

DairyCo’s Marco Winters believes the reason behind their growing popularity is the genetic superiority they offer in comparison to that of older bulls.

And the good news is that resulting daughter proofs for these genomic young sires have already shown to be living up to initial predictions.

DairyCo compared more than 3,000 genomic young sire predictions from April 2012 with their daughter proof information in December 2013.

They found that predicted PLI (profitable lifetime index) scores gave a true reflection of sire capabilities, with reliability increasing by 12% on average.

“The initial genomic predictors of £100 PLI on average in April 2012 turned out as £101 PLI in December 2013 when daughter information was added,” explains Mr Winters.

For more on this: See ‘Guide to using key indicies for dairy bull proofs’

Getting results on farm

Rob Wills, Willsbro Holsteins, Wadebridge, Cornwall

One pedigree breeder more knowledgeable in the field of genomics than most is Rob Wills, who runs a herd of 1,000 pedigree Holsteins in partnership with his father Anthony and brother Matthew.

The family started using genomics when it first became available in 2009 and were the first breeders in the UK to test females and market progeny in a private sale. As a result they have the largest pool of genomic-tested females in Europe, with more than 1,200 tested in total.

“Our goal is to have a herd of high-yielding, long-lasting, trouble-free cows that are sustainable and profitable,” explains Mr Wills.

He uses genomic sires across the whole herd. Cows are artificially inseminated using genomic semen and all flushes are carried out using genomic sires. Currently embryo transfer is used on a proportion of the cows and 90% of the heifers.

He wants genomic bulls that are good on type and production. Somatic cell count (SCC) is also vital, and he looks for no big negatives for calving ease or daughter fertility. “Cell count is one of the highest criteria. We don’t use positive bulls and like them to be big improvers. We have found it to be really accurate.”

The aim is to sell high-quality genetics to other breeders and breed bulls for AI, and the brothers strongly believe genomics is a tool that can help them to achieve this, especially when combined with embryo transfer.

“You can use it to select your best females to breed from at an early age. We use the top 5-10% of genomic youngstock as donors and the rest as recipients. The expense of flushing and recipients is then directed most efficiently and gives best results.”

In fact, he believes genomics offers breeders value for money beyond its ability to offer accurate services. “On the AI side there is no arguing with the best-proven sires, but semen is usually limited and expensive. With genomics you can get more punch for your pound, with only the very early semen from genomics being expensive.”

Mr Wills uses GTPI (genomic total production index) instead of the UK equivalent because he concedes the UK was late at catching up and he wanted to use it early on. Because the Willses sell progeny internationally it also makes sense for them to use a more universally well-known figure.

“You could probably get a 2,300 GTPI bull for £10-20; even if he loses 200 points by the time he gets a proof he will still be 2,100. There are 20-30 proven sires available at over 2,100 GTPI and they would all cost £20 or more.”

Investing heavily in genomics has paid dividends for the family. They currently hold the record for the highest priced female sold at auction with Willsbro Emilyann. She was the number one genomic tested female in Europe at the time and sold for 90,000gns in 2010.

Mr Wills says the improvement in the quality of youngstock bred in the herd is testament to its success.

“We own and have bred 40% of the females in the top 100 GTPI in the UK and more than 50% of the top 100 PTAT [predicted transmitting ability for type] females, so we have an exciting future.”

He believes the UK should have been quicker to embrace genomics.

“Now America’s GTPI brand has become the global language of cattle genetics, with GLPI and RZG following. Although slow to start, Holstein UK and DairyCo released figures last year for females, but more needs to be done to improve this.

“Too many people have invested heavily in genomics for it not to work so there will be great effort to keep improving accuracy.”

So what would his advice be to breeders thinking about using genomics? “Don’t be afraid of it. Just stick to the same criteria you would on using proven sires and make sure they are significantly higher figures.

“Then, even if they drop slightly they will still be OK. And use a good cross section, not too much of a single sire.”

John France, Herdsman at Lowerfield Farm, Northallerton, North Yorkshire

At Lowerfields dairy farm in Northallerton, using genomics bulls is helping to fast-track genetic gain and target higher butterfat percentages.

Herdsman John France selects bulls with high genomic index scores for use on the whole 500-cow pedigree herd. He looks for bulls with a good pedigree, that are +2 for feet, legs and udders and boast PLI scores over £200.

The year-round calving herd is inseminated using DIY artificial insemination.

“By the time a bull is proven it is five years out of date. Genomics offers more advanced genetics and a wider choice of bulls,” he says.

Although it is still “early days”, when the first crop of genomic daughters starts milking in two years’ time he hopes to see a big improvement in production and breed.

The herd already has a high average yield of 12,000 litres a cow a year, however, the farm, which supplies Arla, is targeting a higher butterfat percentage through better breeding to increase milk price returns.

Arla announced last year that any suppliers who increased butterfat levels above 4% would receive an extra 0.25p/litre for every 0.1% increase. “We’d like to increase butterfat by 1% from 3.7% currently and try to breed stronger, better cows,” Mr France adds.

He says he would encourage other farmers to “take the plunge” into genomics. For those still sceptical he suggests using “a bit of both – don’t be frightened.”

Step-by-step guide to understanding and using genomics indices

- Identifying your herd’s strengths and weaknesses. “Don’t just guess, use benchmarking information such as milk records and culling data,” says DairyCo’s Marco Winters. “We also provide an online herd genetic report summary for farmers that milk record, which highlight the exact genetic areas that need improvement. “For example, the Herd Genetic report may show a herd to be in the bottom 10% for female fertility index at -1.3. To correct this, bulls should be used that bring this back to a positive score.” To achieve this, Mr Winters says bulls should be used that have a minimum +1.3 fertility index.

- Selecting sires. Profitable lifetime index (PLI) should be used as the initial screening tool when looking at bull selection. This accounts for a combination of production, health and fitness and type traits, and represents the financial improvement an animal is predicted to pass on to its daughters. But before you assess the criteria make sure it is the UK index, warns Mr Winters. “Selecting bulls on foreign indices such as TPI or EBI will lead to suboptimal selection, as economic conditions on which these are based are not the same as in the UK. “The criteria for choosing a genomic sire or daughter-proven bulls are, in principle, the same. But, because the reliability of genomic young sires is generally lower than that of daughter-proven bulls, the quality of a genomic young sire should be better than the genetic index of the daughter-proven bulls that is being considered at the same time. If it isn’t, look for an alternative that is better.”

- Refining your choices. Your breeding objectives will determine which indices are most relevant to your needs. This will vary considerably from herd to herd, but should include lifespan, somatic cell count (SCC) and cow fertility index. “For example, for herds suffering with a high number of mastitis cases, additional emphasis should be placed on improving genetics for SCC. Similarly, herds struggling with replacement rates should go for higher lifespan indices in the bulls they select,” says Mr Winters.

- Considering conformation. Type traits predict the conformation a bull will transmit to his daughters and will affect their functional traits such as locomotion and udder composite. “Locomotion and mammary have shown to be most strongly associated with longevity out of all the conformations traits and should, therefore, take priority. However, if increased longevity is your aim remember to select on direct Lifespan index first, before fine-tuning your type selection. “Type selection can also help to protect your cows from getting too big or too angular by concentrating on bulls that are zero or less for stature or angularity, respectively.”

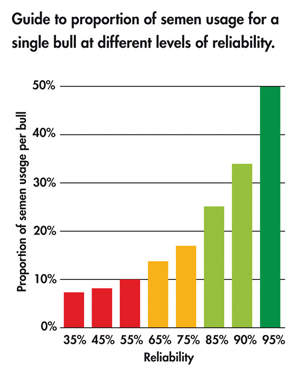

- How much semen should you use? Use reliability figures as a guide as to how much semen to use per bull (see graph). Reliability figures range from 30-99%, with 99% representing the most reliable.

“Genomic young sires typically have a reliability of 65-70% which warrants a degree of caution.” As a rule of thumb, Mr Winters recommends not to use one genomically tested young bull on more than 13% of the herd and don’t gamble on one hotshot bull. “Use four or five as a team. That way you spread your risk and maximise gains,” he adds.