French centre keeps tabs on infectious bronchitis in poultry

Opened in June 2013, the Zoetis centre of excellence in Brittany started testing its first swabs in February. Philip Clarke travelled to France for a look around.

Infectious bronchitis in chickens can be a fickle disease. Like the proverbial box of chocolates, “you never know what you’re gonna get”.

For as well as coming in a variety of shapes and sizes, IB is also prone to sudden mutation, further confounding those whose job it is to keep tabs on the virus.

To try and add a bit of clarity, animal health company Zoetis has set up its own diagnostic laboratory at Torce, Brittany.

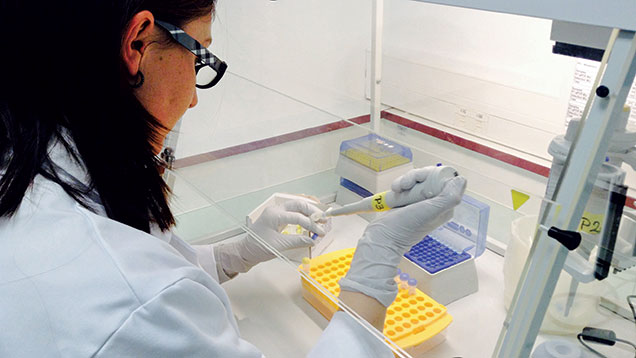

Referred to as the “poultry centre of excellence”, the laboratory employs two full-time scientists, and specialises in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

Practicing poultry vets are invited to send in 10 samples at a time from each shed, to get a better understanding of the disease challenges affecting their customers’ flocks.

Each sample is accompanied by a paper Sample Submission Form, giving full farm and flock details, including clinical signs, disease history and vaccination records. The cost of testing is covered by Zoetis, the cost of sampling by the sample provider.

See also: First infectious bronchitis QX strain vaccine for chickens available

“There are several advantages to doing this work,” says Francoise Blond, who manages the lab. “It allows the vet to understand what strain of IB may be affecting a particular flock. It also helps them assess the effectiveness of any vaccine. And it enables us to build up a picture of the IB situation in the field and offer advice on suitable programmes.”

The data now being produced at Torce builds on the information previously generated by the University of Liverpool, with whom Zoetis had a formal relationship.

By combining the data, trends can be picked up. For example, it is seen how IB strain Ital 02 dominated in 2002-03, and then declined to the point of extinction, as a concerted vaccination programme took effect in affected countries.

It also shows how IBQX has increased steadily in Europe since its arrival in 2004. It has been found in 42% of samples sent to Torce this year. There was some suggestion in UK veterinary circles that the disease may have peaked in 2013 and was starting to drop off. “But our evidence shows that it is on the increase again in 2014, especially in layers. We believe it may have been overlooked in some areas,” says Ms Blond.

“Also, some labs only do direct gene sequencing, which only reveals the main strain of IB on the sample. If, say, Mass is the dominant strain, the results may mask the presence of IBQX. In contrast, the PCR test we do will show everything that’s present.”

Zoetis studies in 2013 showed 793b was the dominant strain in the UK, followed by Mass and Arkansas, mostly strains associated with vaccination.

PCR testing and sequencing

The process is technologically complex. But in essence it involves taking a tracheal or cloacal swab from the bird, extracting the ribonucleic acid (RNA), and then adding specific primers, probes and reagents, and fluctuating the temperature for specific durations.

At Torce, each sample is first tested to see if it is IB positive at all. Then a second PCR is run using seven different primers and probes – one for each of the main strains of IB currently found in Europe. These are 793b, Mass, D274, It02, ARK, D1466 and IBQX.

The results are then compared with the sample submission form to see how they compare with the clinical signs described and any post-mortem examination findings.

They are also compared with the known IB vaccination programme for the flock concerned, to ascertain if it is the vaccine strain or field strain that is causing the problem. If, for example, the PCR shows a positive for 793b and IBQX, but the flock has only been vaccinated against 793b, then the lab will record that IBQX is a field strain of infection, while the 793b is the vaccine strain.

In about 8% of cases, however, the sample will throw up an IB positive result, but will be negative against all seven strains being tested. In this case, the sample is sent away for gene sequencing, to see which known strain of IB it most closely resembles, and what is the degree of homogeneity.

While the PCR process takes up to 10 days to get results back to the sender, sequencing takes longer.

“The other problem is that sequencing only identifies the main strain in the sample,” says Ms Blond. “If there are two or three new variants at play, then they will not show up in the result. Also, it is quite common to get inconclusive results.”

In-ovo vaccination

As well as testing for disease, the centre also acts as a service hub for the company’s Embrex devices – Egg Remover and Inovoject – used for in-ovo vaccinations against Marek’s, Gumboro and Newcastle disease into fertile eggs in hatcheries.

Currently there are about 80 such machines in Europe, the Middle East and Africa – though only two in the U – and a team of 13 technicians services them on a regular nine-week cycle.

Most of the machines are located in France and Spain, where 90% of all Marek’s vaccination is now carried out in-ovo. But the main growth markets are Russia, Turkey and eastern Europe.

As well as commercial hatcheries, a number of machines are used for human flu production. In this case, fertile eggs are injected at about 12 days, compared with 18-19 days for chick production.