Potters Poultry: Growth plans at home and abroad

Industrial conglomerate the Hanson Trust once famously advertised itself as “the company over here doing rather well over there”.

Despite operating on a somewhat smaller scale, the same accolade rings true for Potters Poultry, which has been making steady progress with its overseas business, while growing its share of the UK pullet and layer equipment markets.

The firm was set up 50 years ago and is still in the hands of the same family, with the second generation, Justin and Olivia, sitting on its management board alongside father, Ron. It employs a skilled workforce designing and producing poultry housing equipment, and rears around two million pullets each year.

Potters Poultry has steadily expanded its base, moving from the pullet-rearing farm that served as its headquarters to new premises at a business park in Rugby, which will increase capacity fivefold.

Overseas developments

The company is adapting its equipment, designed with the UK in mind, to suit markets all around the world, formally setting up Potters Poultry International in 2008.

It requires a flexible approach, as evidenced by dealings with Amish egg farmers in the US, whose religion bars the use of electricity. To overcome this, Potters designed and sold a pneumatic equivalent.

That market for “cage free” or barn eggs in the US comprises some 12% of a 360 million-bird laying flock, and represents a big opportunity for the firm.

Part of its export offering is knowledge transfer; sharing practices that the UK poultry industry has developed with those now adopting manure and egg collection belts for the first time.

“It’s been a bit of a learning curve for us,” admits Olivia Potter. “Whereas in the UK you might be dealing with a man and wife, or a single farm manager who is hungry for information, over there might be an overall site manager with a team of staff, who couldn’t care less about bird performance.”

She explains that labour is so cheap in the country that farmers can afford to have workers picking up floor eggs. There have even been examples of birds reared in cages before being moved to multi-tier barn systems – a recipe for disaster.

But now there’s demand for change, and with it comes the challenge of passing on good management practice.

“What they are starting to realise now is the importance of overall egg numbers,” says Justin. “The farmer might have been happy with 260 eggs, but now they are realising there is money to be had in the shortfall [between this and 300-plus]. Some have invested heavily in the equipment and now recognise the need for proper training in how to use it.”

Pullet rearing advances

A similar challenge is presented in the UK market, admittedly one a few years ahead of the US. Faced with a maturing free-range egg industry, the Potters feel it is time to look at pullet rearing, and ways it may be improved.

“We want to double the size of our rearing business,” says Olivia. “The investment and expansion in free range hasn’t filtered back.”

By this, she means not just financial aspects, but the focus on management and performance; getting the best out of the bird increasingly needs to begin from day one, not point of lay.

In a small industry, the two Potters can’t think of more than “three, maybe four” rearing sheds built from scratch in the last 10 years. More often it is broiler sheds coming to the end of their life and subsequently converted.

“You just wouldn’t get a payback on a brand new system,” says Justin. With the figures that broiler farms generate, it is difficult to see why anyone would choose to rear pullets. “They would think you had a decimal point in the wrong place.”

They cite this as one reason behind Potters’ decision to design and build a new “premium integrated aviary” for pullet rearing – a three-deck multi-tier system that broods birds off the floor in a more controlled environment.

The system, which comes to head height, provides feed and water and encloses chicks on paper for the first two weeks of life, making initial vaccination simple. The temperature is also easier to manage, with pullets taken off the cold floor.

Following this, they are slowly granted access to the remaining tiers and the floor as the system in opened up. It saves farmers training birds to roost in their tiers when the stress of manually moving them could disrupt early egg production.

With that in mind, they are aiming at roughly a 40p/bird premium on hens sent through their system, to pay for the cost of their investment and to recognise the improved quality of the birds.

As with Big Dutchman’s equivalent multi-tier rearing unit, the RSPCA, and therefore Freedom Food, has not yet given its blessing to Potters. Instead it has offered it a derogation, classifying the system as a “novel rearing method” while further study is undertaken.

But according to the Potters, the rearing system is designed to match each of the Freedom Food’s stipulations for multi-tier, and ultimately will offer better pullets and earlier lay. “To me it is the way forward,” insists Olivia, “and potentially a big financial gamble for us – but we’re trying to stick our neck out.

“The commercial laying industry needs to move with the times and needs to start investing in rearing. It never has done.”

Anthony Heath: Multi-tier makes for efficiency

The advent of multi-tier has been a major driver in the layer equipment market served by Potters Poultry in recent years.

One producer who has made the change is Anthony Heath, who farms in Shropshire. The need to achieve economies of scale for his business and “move with the times” led him to install multi-tier in three sheds that had previously housed speciality hens.

The three hen sheds originally contained some 36,000 hens supplying speciality eggs to Clarence Court. But with a switch to conventional production came the need to improve his cost of production.

“When you’re selling a niche product, like Clarence Court eggs, flat deck stacks up, but for standard free range you need to be more efficient.”

He has retrofitted the buildings with an integrated multi-tier, splitting the sheds into flocks of 16,000, and now sends brown eggs to Oaklands, up the road. The farm can now house 66,000 layers on the same footprint.

Potters Poultry has supplied the equipment, from the computer systems to the pophole mechanism and muck belts.

“With multi-tier, the birds eat less, there seems to be better ventilation with the manure being removed more regularly, and more birds means more heat.”

Mr Heath says the system, which has had birds in since the start of this year, has made for easy management, too. “When walking the sheds at night, I can see things better, I can reach into the system for floor eggs more easily.”

He adds that the birds seem active, are moving between the tiers and units, and have been ranging well.

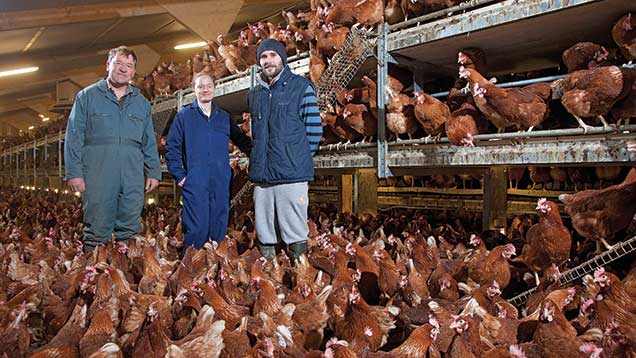

Richard Morris: Free-range production on track

Richard Morris of Great Bowden has been involved in egg production for most of his working life. He has seen small pasture egg production evolve into deep litter, before going into conventional cage production while farming with his late uncle. In 1998 a combination of pressures saw them exiting the sector, but with Mr Morris keeping a hand in, packing eggs for local businesses.

Faced with the inheritance of 36ha of land and the need to create a “cash generating enterprise” on it, after much consideration he decided to invest in free range.

It was a decision seven years in the making, though he says the business had “always kept an eye on” free range. He wanted to be satisfied the system was the highest welfare available, before investing.

Mr Morris went for a 20,000-bird unit, split down the middle creating two “houses” of 10,000. Each side of the shed has its own access to range, and the multi-tier is arranged with nest boxes next to a central egg belt, with a gap to a second unit that provides drink and water.

The first flock is in-situ, and he is “very pleased” with the way things are going. Early production metrics are also looking good, with floor eggs standing at about 1%. Birds in one house were laying at 97.6% when Poultry World visited in week 25.

He has a full time stockworker, Gavin Creesey, who tends to the flock day-to-day.

Eggs will predominantly be marketed through LJ Fairburns, but he hopes to build on his separate packing business in the coming months, sending a small percentage there.