How passive transfer testing gives calves a good start

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan On-farm blood testing to check dairy calves for successful passive transfer from colostrum has helped a 780-cow herd validate its protocols.

Within six months, correlating the outcomes with calf health, Stowell Farms, near Pewsey in Wiltshire, decided to raise their colostrum quality standard.

See also: 7 ways to prevent colostrum contamination

Farm facts

Stowell Farms, Pewsey, Wiltshire

- 780 Holsteins

- 12,000 litres average yield at 4.12% fat and 3.21% protein

- 4 youngstock rearing units within 1 mile radius of dairy herd

- Rearing 320 heifer replacements a year

- Age at first calving rolling average 23.5 months

- Beef-cross calves sold privately at 2-4 weeks

- 1.5-2 full-time staff for youngstock

For herd manager Chris Gowen, this test, with simple traffic-light coded guidance, has allowed him to work out why calves are not absorbing essential antibodies from their first feeds.

It might be an issue with staff, poor-quality colostrum, or stressful handling at that first feed, which, in turn, affects antibody absorption, he says.

Chris Gowan © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

“We changed from 20% to 24% on the Brix refractometer when we got three red results.

“With five ambers, we had a lot of cows calving so there was a potential bottleneck on the system and someone might have been just too busy,” Chris explains.

“We don’t get sick calves – scours is the main thing and they normally cure in a day. Over 12 months, heifer mortality is less than 1%.”

Number of calves and their immunoglobulin status |

|||||

|

Month |

Red <10mg/ml |

Amber 10-15mg/ml |

Green 15+ mg/ml |

Calves with scours/not drinking |

Calves died < 14 days of age |

|

August 2024 |

3 |

1 |

22 |

22 |

0 |

|

September |

2 |

1 |

41 |

24 |

1 |

|

October |

2 |

0 |

26 |

13 |

1 |

|

November |

3 |

0 |

15 |

10 |

2 |

|

December |

0 |

1 |

9 |

13 |

3 |

|

January 2025 |

0 |

5 |

16 |

18 |

1 |

|

February |

0 |

2 |

2 |

44 |

0 |

|

March |

1 |

0 |

32 |

3 |

0 |

|

Source: Chris Green, Stowell Farms |

|||||

On-farm testing

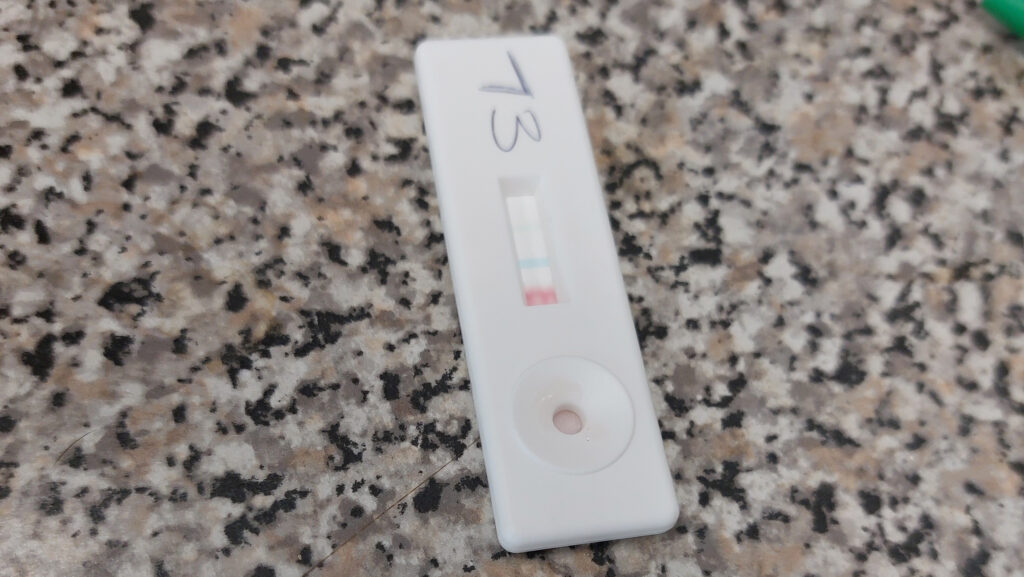

The decision to blood test calves routinely was made easier by the launch of the on-farm kit ImmunIGY Bovine IgG.

This measures immunoglobulins (IgG) in mg/ml and reflects whether a calf has had enough antibodies from colostrum.

Chris wanted to confirm that calves were getting sufficient passive transfer and that protocols were followed correctly to do the best job.

“We used to do blood testing via the vet, but only when we thought there was an issue, so really it was too late.

“This test meant we could do it ourselves and get the results on site within 10 minutes, and for a two- to three-day old calf.”

The benefit of testing at such an early stage is for prompt action: calves with poor results can be fed more colostrum and given more help, says Chris.

He can also investigate causes and take action to prevent problems happening again.

The key is to ensure that calves gain as much immunity as possible to help them fight infection and avert future health issues.

For this herd, youngstock are as important as the 12,000-litre milking cows – heifer rearing management has to produce and grow a quality animal, says Chris.

“These calves are our future herd. We expanded, redesigned and installed robots, so why would we put average heifers into this excellent system?

“We’ve got to give our calves the best start to life. Otherwise all of the money, time and effort put into getting them on the ground is pointless.”

The farm retains 320 heifer calves each year as replacements, joining the herd at a target 24 months and calving at 550-600kg.

For consistency, the main calf rearer, Peighton Robertson, does all of the main feeding, bedding, weighing and treatments in the mornings.

Peighton Robertson © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

This allows staff on rota to just feed and check calves in the afternoons.

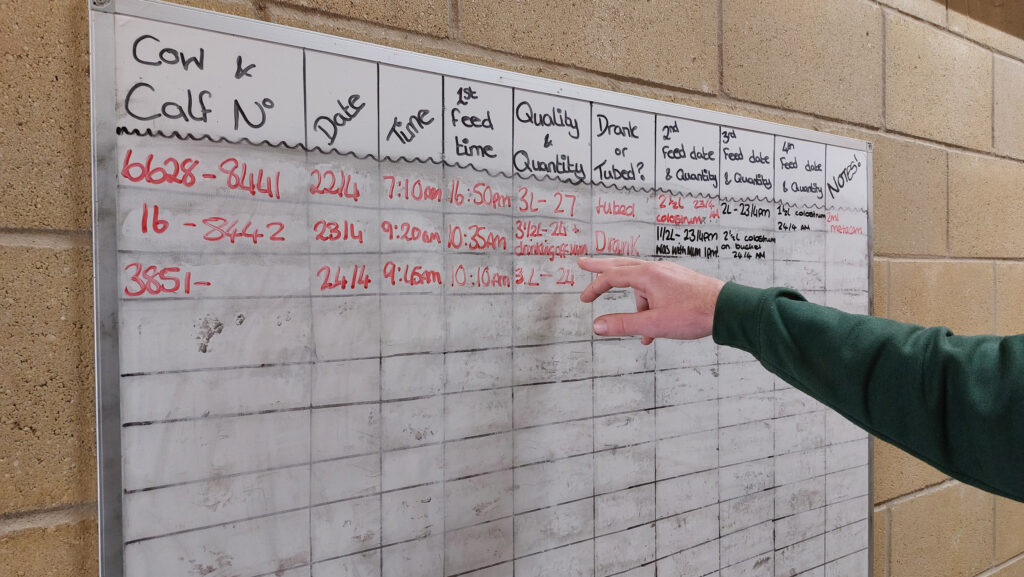

There is also a detailed whiteboard to record all treatments, feeds and colostrum quality so that any of the farm’s 10-strong team of staff can keep up to date.

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

Colostrum quantity

Life starts with 4 litres of warm colostrum within four hours of birth for all calves. This is fed by bottle and teat, as Chris thinks it’s less stressful for the calf.

First colostrum is harvested in the calving pen using a portable machine while the cow eats. However, to save time on the night shift, frozen colostrum is thawed and warmed.

“The calf also drinks from mum and we feed it again two or three times; we offer 4 litres, but if it is full it might only take 1-2 litres,” he adds.

Navels are dipped with 10% iodine, the calf is tagged and an ear notch taken for genomic testing.

Within 24 hours, Peighton moves each calf into a mobile isolation box where it stays for the next 24-48 hours, being fed a further 2.5-3 litres of colostrum before transitioning onto milk replacer.

Calf isolation box © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

“When it’s drinking well, it then goes to a hutch where there is also water and concentrates,” she says.

Once calves are drinking well and thriving, they are transferred at about 10 days of age to one of the four rearing units overseen by youngstock manager Nick Strong.

Since August 2024, Peighton has blood tested every newborn dairy heifer in the isolation box for passive transfer.

She says it’s usually an easy “two-second job” though it can vary from calf to calf.

Taking a blood sample © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

A lancet pricks the top of the calf’s nose and Peighton collects a blood sample, which is dropped into a bottle of buffer solution and shaken.

“It’s like a Covid test as we put the sample in a lateral flow device, then we use a reader to get the IgG level on a scale of 0-40mg/ml. Our goal is 40mg/ml.

“I record the results in a paper diary, which is uploaded to Uniform-Agri weekly by Chris,” she says.

The test uses a lateral flow device © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

Test results

For ease, the results are interpreted as red, amber and green to illustrate poor, borderline and optimum passive transfer. Chris says they want all green results, and zero in the red category.

He has found that some calves do not absorb antibodies as well as others and it is thought this may be genetic.

In future, this might lead to monitoring a cow family and it is important to be able to relate it to illness as Chris wants to breed a healthy, profitable animal.

Ideally, he says a software program would track calves all the way to calving, to be able to relate level of passive transfer to performance (such as growth rates and milk yield) plus sickness and treatments.

He is keen to know if colostrum quality and quantity can have such a far-reaching effect.

But even though results are now consistently in the excellent category, Chris says the plan is to keep testing: the cost and time is worth it to rear the best heifers.

“They are a valuable asset to the farm and need to achieve their potential,” he says.