Drones could bring benefits to arable farmers

For anyone even half interested in flying model planes, Project Ursula is a gift – the chance to become involved, if only as a spectator, in the commercial use of unmanned planes to provide remote sensing of a crop’s condition.

Project Ursula began life two years ago as a research tool to explore the potential for imaging crops. It primarily involved high-input, high-value crops such as potatoes, vining peas or sugar beet, but it’s relevant to larger areas of cereals, too.

Supported by the Welsh Assembly, it brought together two companies – remote sensing specialist Callen-Lenz and Environment Systems – and was based at Aberystwyth. The plan now is to create a new company in East Anglia called Ursula Agriculture, which will be offering its crop scanning services to arable farmers.

Project manager Mark Jarman (pictured below) points out that flying an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) equipped with a sensor at heights of about 300m produces a much higher resolution picture than one taken from a satellite – the system currently used by a number of companies.

Cloud cover

“Satellite images, due to the distances involved, have a much larger area covered by each image pixel and cannot work effectively when there is cloud cover – which in last year’s inclement weather was often the case,” he explains. “Our UAVs can fly under cloud cover and produce pictures at a resolution of up to 3cm/pixel, which allows much more accurate analysis of the crop and its condition.”

“Satellite images, due to the distances involved, have a much larger area covered by each image pixel and cannot work effectively when there is cloud cover – which in last year’s inclement weather was often the case,” he explains. “Our UAVs can fly under cloud cover and produce pictures at a resolution of up to 3cm/pixel, which allows much more accurate analysis of the crop and its condition.”

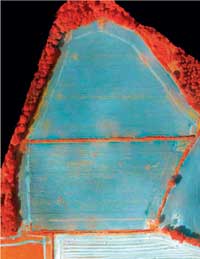

Different sensors – visible light, infra-red and thermal – are used to identify different features of crops and the past two years have been spent creating a database that will, for example, recognise weed types, the presence of disease, plant stress levels, crop damage, crop yield potential, chlorophyll content and N requirements as a result.

“Weed identification and its precise location within a field could, with a GPS-programmed sprayer, result in localised spraying and a big saving in chemical costs,” he says. “Similarly, information could be used for variable-rate nitrogen fertiliser application – it’s all about interpreting what the images produced are telling us.”

Mr Jarman adds that a sizeable database has already been created, but it is ongoing work that will be expanded as different crops and conditions are encountered.

Compressed air

The 5kg, 2m wingspan Callen-Lenz UAV is electrically powered and launched from a ramp using compressed air. Its route is pre-programmed and guided by GPS, although control can revert to a CAA-licensed “pilot” on the ground if required.

The 5kg, 2m wingspan Callen-Lenz UAV is electrically powered and launched from a ramp using compressed air. Its route is pre-programmed and guided by GPS, although control can revert to a CAA-licensed “pilot” on the ground if required.

It flies in bouts 60m to 220m apart at a height of 300m, with images taken automatically every few seconds. These are then downloaded at the end of each flight in a control vehicle parked nearby.

It can stay airborne for about 50 minutes, but is normally brought down after 30 minutes of flight and given a fresh battery

The best conditions to fly in are when there is a cloud base which gives a neutral light and prevents direct sunlight creating shadows. However, operations can continue throughout the year in most weathers, including winds of up to 30mph.

On a good day the two-man team can normally cover several farms and can have the data back to the customer the following day.

“The speed of processing imagery is essential if the full value of the job is to be realised. There is little point giving a farmer details of a diseased crop a week after the pictures were taken,” says Mr Jarman.

Costs have yet to be fully determined but Mr Jarman believes they will be in the region of £10-£20/ha depending on the size of the area to be scanned.

For the future, UAVs could be much larger, with a greater operating range. “The potential for this sort of work is, we believe, vast,” he says. “It gives a new dimension to precision farming and provides growers with the detailed information they need to manage their crops.”