Workshop Legends: Articulated tractor king John Nicholson

John Nicholson © Nick Fone

John Nicholson © Nick Fone If you set out in search of advice on high-horsepower artic tractors, your quest would probably immediately take you across the Atlantic.

But hidden deep in North Yorkshire there’s a source of encyclopedic knowledge on the subject.

For the last 40 years, farmer and engineering enthusiast John Nicholson has been running, repairing and restoring big, prairie-style pivot-steers.

There isn’t much he doesn’t know on the matter, his all-encompassing interest coming from a deep-seated passion for modifying and improving farm equipment that stems back to the 1960s.

See also: Workshop Legend: We visit master tractor fixer Martin Percy

Where did you learn your trade?

I was really lucky growing up as we had an ex-army mechanic working on the farm and, from the age of seven, he’d spend hours in the workshop patiently showing me how to take things apart and repair them.

It gave me the bug for spannering and machinery.

Very unusually, at school we were taught about metalwork and metallurgy. It was the one thing I actually applied myself to.

I put all my effort into learning about alloys, different sorts of steel and hardening. Later in life, this knowledge became incredibly valuable.

© John Nicholson

How did you start out?

The first project I was allowed to undertake was to help convert ex-army troop carriers to tipping trailers.

After the war there were heaps of olive drab kit all over the country with nothing to do, so farmers tended to make use of it.

We had bought some US Army Ford Canada 4×4 articulated lorries, which my father envisaged being useful in carting grain and muck.

We had to fabricate a long drawbar that ran right back to the axle, with a hydraulic ram to tip the body up into the air.

It was the axle that acted as the pivot so there was a lot of force going through the whole frame.

We quickly learned the drawbar had to be well braced and reinforced otherwise it would just bend and break.

What were your key tools?

Growing up I was fascinated by welding. We had a Triang arc welder in the farm workshop that I would spend hours experimenting with.

You had to be quite careful with it as it would give you quite a shock if you got the earthing wrong.

Most complex project?

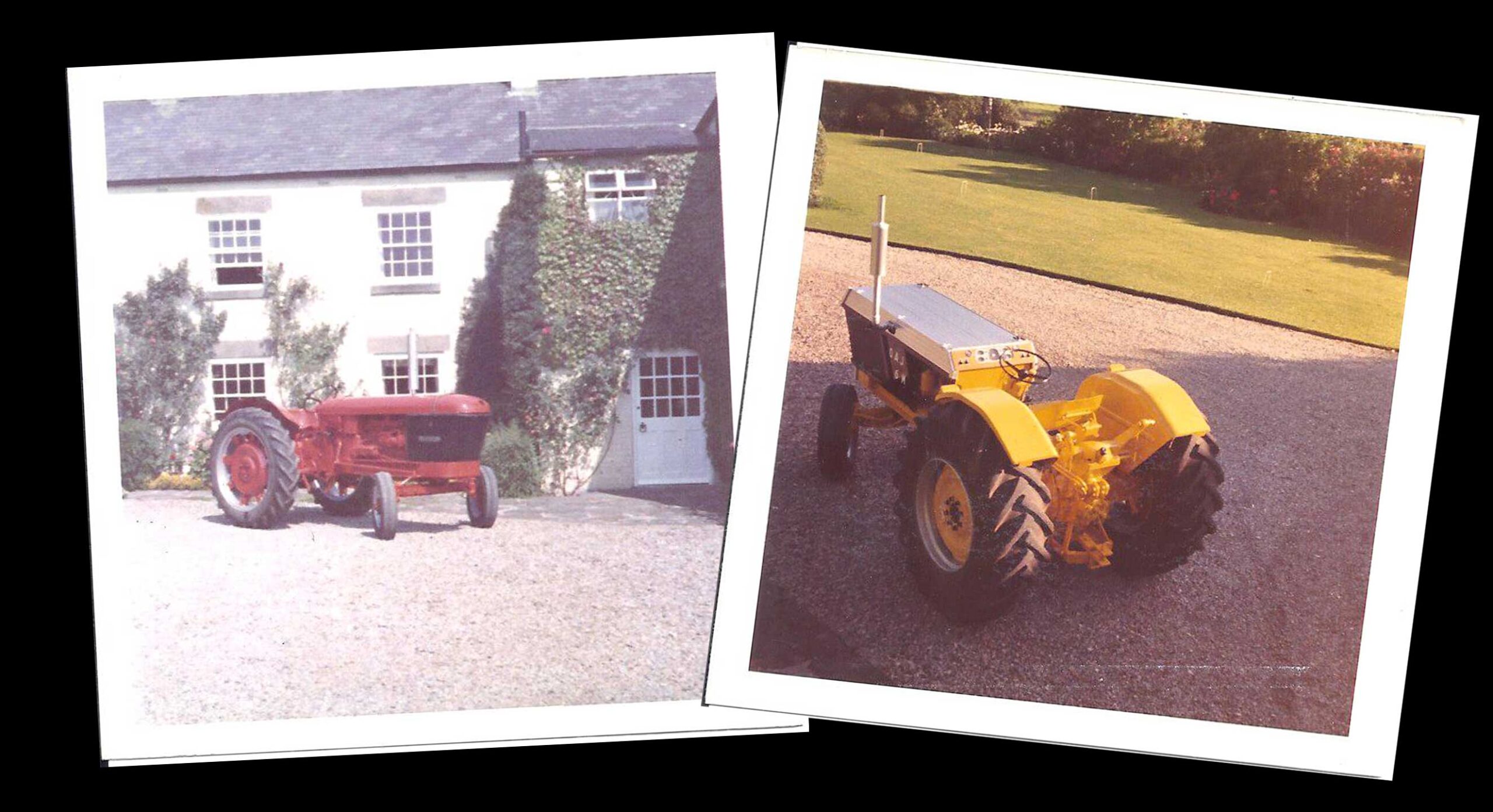

My father always opted for the biggest tractors on the market as a means of getting fieldwork done in a timely fashion, but back in the 1950s and 60s, the largest prime-movers struggled to make 60hp.

He would go to the Smithfield Show and argue with Lord Nuffield about the need for a six-cylinder engine with more power but failed to persuade him, so in 1963, we set about converting one of our Nuffield 460s.

We took a 5.1-litre BMC engine out of a Post Office lorry and started the process of chopping the chassis about to accommodate it.

We cut the side plates and used channel and flat bar to stretch the frame by 9.25in.

Marrying the flywheel with the Nuffield gearbox was relatively straightforward, but taking the tractor from 58hp to 105hp did have an impact.

The back-end on those tractors was tough but the brass-caged pinion gear bearings couldn’t stick the extra abuse so we replaced them with larger steel-shelled versions.

The added weight of the additional two cylinders and stretched chassis also made the 460 virtually unsteerable.

© John Nicholson

The engines already had power-steering pumps so we just stripped the rest of the gear off the donor Post Office van and grafted it onto the tractor – problem solved.

Inevitably, though, that just triggered another issue. The extra forces generated would twist the front axle, so we had to add an A-frame and beefier king-pin bearings.

It proved a big success. That first tractor would go out and do almost twice the ploughing the standard 460s were managing. That gave us the confidence to try the bigger 5.7-litre BMC engine.

Fitted to a Nuffield 1060, it generated 120hp and was another step on again. Following that, more 465s were converted in a similar manner.

Word began to get round about the daily acreages our ploughmen were managing.

Other farmers soon started enquiring about their own six-pot conversions and over the course of the next few years we did many Nuffields. Most were 465s, but we also did a Leyland 384 and a 4wd Bray 465.

It was that last tractor that really made us stop and think. We’d solved the power issue with the bigger engines but traction was now the limiting factor.

© John Nicholson

What was the next step?

We fitted wider, taller tyres front and back, which helped with carrying the extra weight and gaining grip, but it wasn’t enough.

We even went down the route of Rotaped “square” tracks. With their massive hinged aluminium pads and huge drive-wheel they were great, but we couldn’t keep the nose of the tractor on the deck.

It was about that time a very unusual beast appeared at the Smithfield Show from behind the Iron Curtain.

With its engine hung right out over the front axle, the Hungarian-built Dutra caught our eye. We’d taken on heavy clay land and needed a tractor capable of putting its power down on the ground.

It ticked the boxes, so we signed up for the one on the stand.

There started my infatuation with modifying and improving slightly-off-the-wall, high-horsepower tractors.

The Dutra was competition for the Muir Hill 105 but lacked one vital feature. Unlike the Old Trafford-made tractors, it had only one diff-lock – on the rear.

So we stripped the back-end down, copied the differential collars, yokes and locking dogs, and fitted a similar arrangement to the front axle.

Dutra was very impressed with what we’d done and from then on offered a locking front diff as a factory option.

Being primarily used for ploughing, correct weight transfer to the rear axle was imperative, so we also developed a crude form of top-link draft sensing.

Like the Ferguson system, it used a coil spring and plunger valve to lift the implement as required.

Dutra initially took this idea on, but later swapped to a superior Steyr draft/position control.

Over the time we’d spent modifying the tractor we’d built a close relationship with Dutra’s engineering team, particularly with regards to the component hardening processes.

So, as a thank you for all our work, they took it away and rebuilt its gearbox with upgraded parts. We were also gifted a second tractor by the Hungarian company.

It behaved like a totally different machine. Its longer-stroke Csepel engine was so much better than the fast-revving, harsh Perkins 6354 fitted to our first tractor.

And, thanks to the new hardening process, it didn’t snap half-shafts.

Dutra © John Nicholson

Any other mods?

Following the Dutras, we ran a number of County 1454s which inevitably got some modifications.

We’d found they just couldn’t generate the power they needed when pulling a five-furrow plough in tough conditions because the intake air was too hot.

Using an old Nuffield battery box, a belt-driven water pump and seven Granada heater matrixes all soldered together with copper pipe, I created an intercooler that then meant I could fit a bigger turbo. More air and more fuel.

To avoid any gearbox and hydraulic issues, I also installed a pair of oil coolers in V-form ahead of the main radiator, along with extra filtration.

It worked – we dyno tested the first one and it went off the scale, at 240hp.

It happily ran on like that for 3,000 hours which gave us the confidence to make similar mods to other 1454s.

With most we stuck at a more sensible 180hp, which meant we could do without the intercooler.

© John Nicholson

What got you into American tractors?

In 1984 I went to look at a second-hand County for sale at Murleys in Warwickshire, but I was distracted by something altogether more interesting.

Tucked at the back of a shed was a 1980 Steiger Cougar 270 which had 3,500 hours on the clock and had been imported from Holland. I’d always liked the American artic principle of equal weight distribution.

At £16,000, it seemed top dollar at the time but I was so convinced that I took it and the County. A fortnight after, I bought a second Steiger for £9,000, despite not having tried either.

They both went to work that July but I immediately realised I’d made a big mistake – they had the grip but lacked the power needed to haul our cultivators about at a decent pace.

Two weeks later, in a fit of enthusiasm, I went out and bought two Panther 325s.

The combination of that extra 45hp and the bigger capacity Caterpillar straight-six made all the difference – they had oodles of grunt.

From there the die was cast – American tractors were my thing.

Having gathered up four prairie monsters in just a few months, word spread that some idiot in North Yorkshire was amassing a collection of American-built artics.

Soon I was getting calls from dealers all over the country asking if I’d take their trade-ins – Steigers, Ford FWs, Versatiles, John Deeres, Masseys and Case IHs.

I’d clearly gone soft in the head because I found it impossible to say no.

They’d come into the yard, we’d put right any faults and then run them on our own farms before putting them up for sale and moving on to the next. It was a cheap way of farming.

With that came a large appetite for parts. So, when Ford management needed to free up some space in its warehouses by getting rid of the green-painted Steiger spares that were used to keep its fleet of FWs running, I leapt at the chance.

Not really knowing what I was buying, I had a surprise when five lorry loads of wheels turned up in the yard that harvest.

Further hauls of heavy metal followed – we were really scrabbling around to find shed space for it all.

But it turned out to be an inadvertently shrewd move. I then had the spare parts business for all lime green and blue artics in the UK – well over 200 in total.

In 1984 we had four Steigers on the farms. By 1992 we had 22 parked in the yard and to this day we’ve had more than 300 artics pass through our hands, many of them swapped in four or five times for refurbs and repair.

What did you find most interesting?

Chatting to the owners of these big prairie monsters, it quickly became apparent that we in Europe wanted something very different to US farmers.

Our soils are generally moister, so we need lower ground pressure and yet more muscle – a totally different power-to-weight ratio.

Rather than a Steiger Tiger, European farmers needed a lighter “Tigress”, so in 1990 we set about building one.

We took a Panther chassis and stretched the front end to accommodate an 18-litre Caterpillar V8. Initially, cooling issues meant we down-rated it to 470hp, but we sorted that out and got power back up to 525hp.

Knowing the limits of Steiger’s axles, we reworked them with bigger diffs and different planetary reduction hub gears. They were designed to go up to the 600hp mark.

Since then various different versions have followed, with narrow and wide-bodied chassis and a selection of Cummins and Cat engines driving through six-speed Allison powershifts from 150t quarry dumpers.

Tigress © John Nicholson

Biggest machinery bargain?

We once sold a Ford FW60 Automatic for £34,000 to Eurotunnel, where they put it to work on a beach. Three days later they managed to get it bogged down, the tide came in and swamped it.

We were asked to go and recover it. We paid them £3,500 for salvage, got it home, washed it off, and changed all the oils, cab trim and batteries.

We’d only just re-painted it so there was very little cosmetic work to do and the metalwork didn’t suffer. It cost less than £2,000 to put right and two weeks later I sold it on for £34,000.

We were lucky. It could have been a lot worse if someone had turned the ignition key post-flooding.

© John Nicholson

Biggest machinery disaster?

In the 1970s my father asked me to build a bale transporter to his specifications. It would stack packs of six conventional bales five-high, but on its first run out it just folded in half.

He’d seriously underestimated the weight it was carrying – it was scrapped and replaced with two Browns bale stack squeezers.

Project you’re most proud of?

As agrochemical use grew in the 1960s, I became increasingly frustrated with wasteful chemical overspray and seeing the crop run down by the sprayer wheels.

To increase accuracy and reduce trampled “green ears”, in 1967 I developed a tramline system for our International drill.

It used a modified Lucas wiper motor to shut off the seed outlets for the wheelings where the sprayer and fertiliser spreader would run, but the driver had to remember to turn them on and off.

The 1968 version had an automated electronic system added that counted the passes and activated the shutters. This, and a hydraulic version made in 1971, continued to be used on the farms.

They were the forerunners to what you find on most seed drills today. The first commercial prototype “tram-liner” was fitted to a Massey Ferguson drill and appeared on the BBC’s Tomorrow’s World in November 1973.

What are your favourite tools?

The mag-mount drill has made our pillar drill fairly redundant. And a 100t workshop press can save hours, and help to avoid damage from a hammer.

Advice for someone starting out in ag engineering?

Learn how machinery works so that you can be an engineer or mechanic, rather than just a fitter.

Nevil Shute once wrote: “ A good mechanic can do for a bob what any fool can do for a quid” – probably because the good mechanic understood how it worked.

Learn how electronics work and how to diagnose faults. Today’s machinery won’t run without them and, despite being a pain, they’re invaluable in making complex kit run as it should.

In a design, look for the one that’s beautiful in its simplicity.