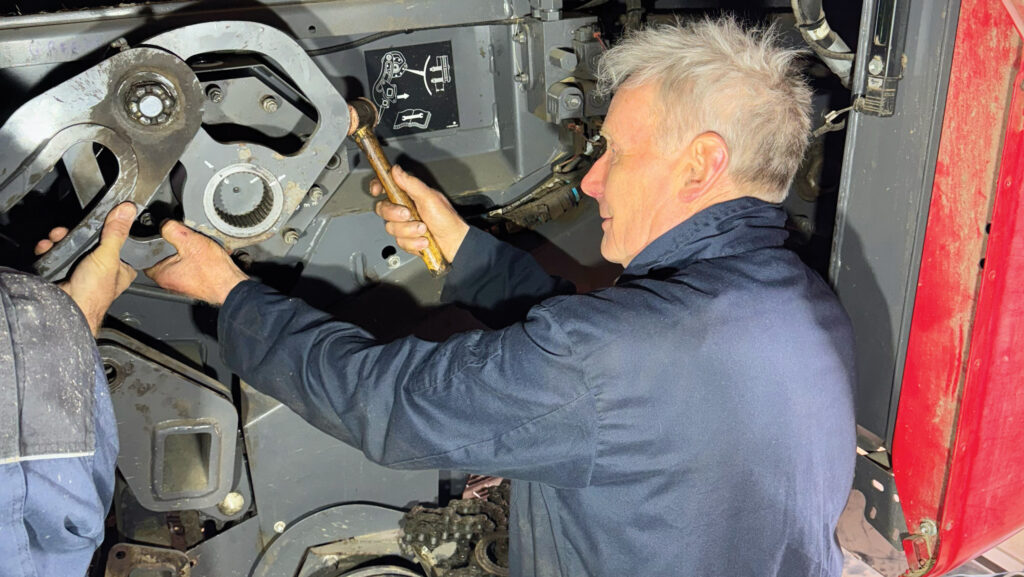

Workshop Legends: Warwickshire College lecturer Tym Morgan

© MAG/Olliver Mark

© MAG/Olliver Mark Thousands of students, and many readers, will have learned how to operate, maintain and repair agricultural machinery – or come to appreciate their mechanical limitations – under the tutelage of Tym Morgan.

He held post at Warwickshire College of Agriculture for 35 years in a career that, in the case of this writer and many others, spanned two family generations.

Now 78, Tym is long retired from the chalkboard and spends his time running a small arable farm, repairing machinery, and chipping in at his son-in-law’s contracting business in Gloucestershire.

See also: Workshop Legends: Articulated tractor king John Nicholson

© MAG/Olliver Mark

How did you get into farm machinery?

My father was mechanically minded, so from a young age I helped with machinery repairs and maintenance on our family farm in north-east Derbyshire.

I learned a great deal from him. My first job, when I was seven or eight, was returning wires on a stationary baler and, by my early teens, I was replacing head gaskets on Fordson Majors.

When I was granted a place at Cirencester College, I first had to do two years of work experience, which took me to a farm in Huntingdon.

The boss soon realised I was handy with spanners and had me fixing all sorts of stuff, from Massey 780 combines to Bedford lorries. I often learned by making mistakes, but I enjoyed the responsibility.

I then got my national diploma in agriculture.

Though the course involved very little practical work, I really enjoyed the machinery lectures by Harry Catling – who was my role model at that time – and the inter-college ploughing matches, for which I was captain.

Where did you learn your trade?

Post-college, I got a job as a trainee service manager at the Bracknell branch of machinery dealer Gibbs, which sold David Brown tractors and New Holland combines and balers.

It was most unusual to get such a senior job so early on, and I was in at the deep end. It was a steep learning curve, especially when I was having to tell far more experienced blokes what to do.

The depot closed a couple of years later, as Bracknell was a developing town and the land was hot property, so I moved to the parts and service department of Broughton & Wilks in Banbury.

© MAG/Olliver Mark

Why did you start teaching?

I wasn’t enjoying the job and happened across an advert for a role as a lecturer at Warwickshire College of Agriculture. I got it and, despite having no teaching experience, was soon promoted to head of department.

But I was conscious about losing touch with the practical side through spending too much time in the classroom, so to keep my hand in the game I’d go out repairing for other people in the evenings and on weekends.

The Association of Lecturers in Agricultural Machinery also put on good training sessions during the school holidays and took members out to visit different manufacturers – Ford, JCB, Massey and the like – to keep us up to date with the latest developments.

And I signed up to several evening courses – one on construction plant and another on mechanical engineering at Banbury. It taught lathe work, milling and metallurgy and was a marvellous introduction to precision engineering.

How has the curriculum changed?

The 1970s and 80s proved a great time to be involved in education. The college was a vibrant place to be, there was plenty of money about, and we had the latest machinery for students to work on.

At that time, people appreciated the importance of proper training, and, as a result, the pupils were always well motivated.

In my view, education – particularly for agricultural students – has gradually gone downhill, especially given the loss of practical elements that gave them the opportunity to learn and implement skills relating to regular farm tasks.

For instance, we used to run a two-week “initial training” course after the Royal Show.

It dovetailed nicely with the college calendar and was designed for school leavers, many of whom were farmers’ sons, before they started working on farms.

It covered all the basics; we’d run an hour’s session simply on filling and using a grease gun, and spend a few days teaching them about tractor driving, roping loads and handling livestock.

These skills would set 16-year-olds up for life.

Then there were the full-time courses, where we’d take them ploughing, drilling and forage harvesting on college land and neighbouring farms.

That got us plenty of brownie points from local farmers as they got the job done for free – all they had to do was stick some fuel in the tank.

In the late 1990s, the college took on a contract with Agco to train apprentices from across the country, and we also ran a Maintenance and Repair of Agricultural Machinery (MRAM) course from November to February.

It was designed for people that had already started their farming career and covered fault diagnosis and repairs of engines and cooling systems, clutches and gearboxes, and hydraulics and electrics.

But nowadays, students go from school into a watered-down, largely paper-based national diploma that, in part because of health and safety, is bereft of those critical practical modules.

It’s particularly sad to see colleges recruiting contractors to do their fieldwork.

Some of it comes down to finances. Colleges now have huge overheads, and they don’t have access to the equipment – brand-new County and Ford tractors, ploughs, sprayers, and so on – that we had in our heyday.

© MAG/Olliver Mark

Best and worst things about the job?

Students were the best. There were some wonderful characters, they were always a good craic, and I got the knack of bringing any troublesome ones into line.

The art was in getting the other students to pull the wildest ones down a peg or two. Coming up with a tongue-in-cheek nickname often proved a successful way of doing so.

The worst was the administration. I dreaded the job of link inspector for a college inspection, which was incredibly demanding, there were governors’ reports to produce, and, for a while, I was responsible for timetabling, insurance and budgets.

If the equine lot wanted more money for something then they’d have to come cap in hand and ask for it, and I tended to have a tight grip on the purse strings.

I never particularly enjoyed the administrative burden, but it’s less about what you do and more who you do it for – and the principal was a nice chap.

Any calamities over the years?

The way we ran things was that local farmers would send in their machines and provide the parts – or students bring in their own – and we’d do the labouring for free.

With so much practical work going on – engine rebuilds, transmission overhauls, electric rewiring and hydraulic repairs – there was always the chance that a student would drop a clanger.

There was no way we could check every nut and bolt and there were occasions when I’d have to go out and sort things after the tractor had been returned to its owner.

The gaffe that sticks in my memory was caused by a little thrust washer that sat between the half and quarter shafts on an epicyclic final drive.

It should have been stuck in place with Vaseline, but the student dropped it, and it went on to damage the final drive ring gear at great expense.

Favourite machine to work on?

The Dronningborg-built 30/40-series Massey combines. Their reputation goes before them, but I enjoy sorting out the problems, most of which are electrical.

Plus, I have got to know them well. The same goes for Massey 135s and Ford 5000s – they were about when I started work and, 50 years later, I’m still repairing them.

I could almost rebuild a Perkins three-cylinder engine in my sleep.

Most challenging repair?

Every job throws up a challenge of some sort that you must find a way around. It’s just part of the process and, with patience and perseverance, nothing need become a major saga.

Several have proved particularly testing, though.

One was extracting and overhauling a relatively uncommon Brockhouse powershift transmission from a Track Marshall 1500 loading shovel at college, which was a bit of a palaver because no one knew much about how it worked.

Another was replacing clutches on Allis Chalmers EA combines, both in the early years at Gibbs and later as backhanders for local farmers.

There were two options for hoicking it out, neither of which were straightforward – either shifting the axle and gearbox forward or cutting a chunk out of the frame, before welding a modified strengthening piece back in.

How do you deal with issues that seem impossible?

The solution usually comes after a night’s sleep, whether it’s what approach to take, what to try, or who to ask.

The key is to go back to basics and work methodically through the possibilities. It’s easy to get caught out trying to diagnose a problem only to find it’s a fuse.

But you can only apply this principle by understanding how the thing works. It’s no use fault finding unless you know what every valve, spring and feature does.

For hydraulics and pneumatics, that means getting the measure of BS.2917 fluid power systems diagrams. Once you understand the circuit, you can start isolating elements until you get to the bottom of it.

Modern tractors are no different, but there are plenty of opportunities to slip up – particularly where electrics are concerned.

Often, seemingly unrelated components can affect one another simply through their sharing of a blown diode or fuse. That’s where studying diagrams and circuits comes into its own.

And there’s no shame in asking someone for advice. Fortunately, many of the students I’ve taught over the years are in the business and happy to share information.

© MAG/Olliver Mark

Favourite tool?

Beyond the obvious ones, it’s a £70 seal twister I bought from America that twizzles them kidney shaped to go into a hydraulic ram.

Kneepads in boiler suits are superb things, too, and magnetic lights make life so much easier as you can get a good look at a combine throat with the risk of cutting or snagging a lead.

Best improvement in farm machinery?

Pto end cap greasers have to go down as one of the biggest advances in my working life. It might be a small thing, but it’s satisfying to know you can always get on the nipple.

Most memorable machine?

The Massey 30 drill. It had so many new features for its time, was durable, capable of working in any conditions, and easy to set up.

There were thousands of them about and it’s still a good machine today.

Its only shortcomings were that it had a habit of creeping out of work without lock-offs on the tractor spool valves, and the size of the hopper for oilseed rape drilling.

You had to throw in more seed than you needed to ensure all the coulters were fed, so there was no avoiding leaving a few acres’ worth inside. It didn’t lend itself to filling with big bags, either.

I’ve still got a 4m model, and I’m living the dream when I’m pulling it with my 7810 on dual wheels. The only thing that beats it is combining with the Massey 40.

© MAG/Olliver Mark

What do you think of modern-day kit?

There have been some remarkable developments in farm machinery.

Once you’ve had a taste of autosteer and headland management, who would want to go back to pulling levers and marking out fields the old-fashioned way?

Yet I would always rather set a combine up by choosing my own settings rather than pressing a button for a particular crop, and emissions systems are nothing but bad news.

AdBlue and EGR cause no end of headaches.

As for other equipment, the biggest improvement is fertiliser spreader control.

A novice operator can be sent to a grass field and, provided they keep within the bout width, they can go round trees, troughs and anything else and still deliver the correct application rate.

Advice to someone starting out in ag engineering?

Make certain you want to do it. Long hours working in field conditions aren’t everyone’s cup of tea.

And be patient. Something that might seem simple could end up taking ages, but frustration doesn’t speed up the process.

What do you do now?

I have 45ha of arable land around my sheds and workshop, most of which I bought when my father sold the family farm.

Alongside that, I help my son-in-law, Vince Janes, who started his contracting business 17 years ago.

At that time, I reduced my college hours to help him out, driving during the season and repairing in the winter.

But he’s well established now, and I’m getting older and less enthusiastic about roaming around with the baler into the early hours.

And I’ve always got a few workshop projects on the go, mainly repairing classic tractors, servicing and overhauling combines and balers, and rebuilding engines for JMT Engineering, which is more than enough to keep me busy.