Lancashire engineer modifies mint Claas and Deere combine fleet

© James Andrews

© James Andrews Few combine harvesters leave a contracting business in better condition than when they arrived, but that’s usually the case for the cosseted examples run by Lancashire outfit A Johnson Agricultural Contractors and Engineers.

Even though most of the machines purchased by owner Alan Johnson arrive in tidy used condition with low hours on the clock, each is overhauled in meticulous detail to make sure it is functioning at its best.

See also: Guide to buying a used hill-sider combine

Added to that, any poorly finished paintwork is sandblasted and resprayed to give a better-than-factory finish.

Once their induction is complete, a fastidious maintenance regime ensues for the rest of their tenure.

This includes a thorough blowing off with a screw compressor at the end of each season before the bodywork is sprayed with a protective diesel/oil mix and any exposed metal is coated in an anti-rust compound.

Andrew Atkinson (left) and Alan Johnson © James Andrews

Even the removable body panels are well looked after, placed neatly on pallets topped with old carpet whenever they are taken off to reduce the risk of them getting scratched.

The only time these machines see a pressure washer is just before the start of the season, when they’re cleaned up ready for action.

This keeps them looking smart, while removing the risk of water working its way into bearings and sitting in any recesses over winter.

Although engineers spend thousands of hours honing the design of these machines, Alan and his team are continually coming up with ways to make them work better.

Most are subtle mods that make them nicer to drive, but there are also significant adaptions that improve performance in the challenging conditions they often face at harvest.

Many of these are down to the soft “moss” soils in the area, which can see machines sink in up to their axles, even in high summer.

© James Andrews

For this reason, all his combines have some sort of four-wheel drive system and are set up to run dual wheels.

When he’s not using or maintaining combines, Alan carries out vehicle recovery with a home-made winching tractor and he runs an agricultural engineering business, specialising in building elaborate custom kit for local veg growers.

This means he’s got a well-appointed workshop at his disposal for the combine work, most of which he carries out himself.

For any wiring or computer-related tinkering, he’s helped by electrical engineer Andrew Atkinson, who spends much of the summer away driving combines – a far cry from his day job fitting out commercial cinemas.

Below, we’ve picked out a few of the duo’s recent adaptations.

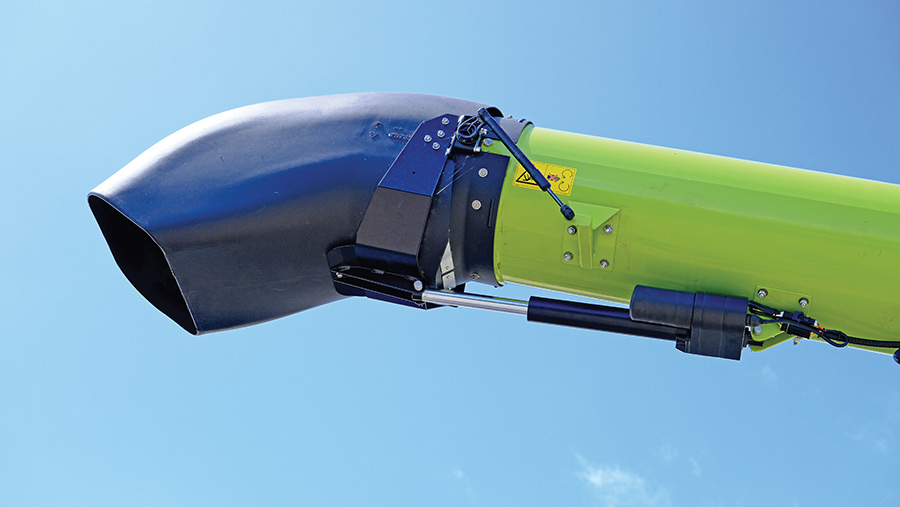

Lexion 750 adjustable spout

After purchasing a 2017 Lexion 750 last year, Alan and Andrew soon realised that its combination of 31ft header and XL unloading auger forced trailers to run on the straw when unloading.

They didn’t want to fit a larger auger as it would stick out at the rear and make the machine difficult to manoeuvre into tight spots, so they decided to get the tractor and trailer running between the combine and the swath.

© James Andrews

The first attempt involved swapping the original auger with a standard-length tube from the 630 they were trading in.

The two are interchangeable, so the switch was simple enough, but the positioning still wasn’t perfect, meaning they had to run it at a slight angle.

After seeing an adjustable chute on the new Trion they reckoned this would give them enough additional movement, so they decided to make their own version.

The plastic chute and tilting mechanism were genuine Claas parts purchased at considerable expense, but the pair sourced their own electric 350mm linear actuator and Andrew built a swish control system to operate it.

This taps into the main joystick so that the toggle lever on the rear – normally reserved for the manual header tilt function – can be used to push the chute back and forth.

Cleverly, the function of the switch changes as soon as the unloading auger is pushed out and it resumes its header duties as soon as the tube returns to its park position.

He’s also fitted an override switch so that the header can be tilted if needed during unloading.

To avoid any risk of the chute hitting the bodywork of the combine as the auger is folded in, a sensor triggers the ram to push it out to a safe position.

It also moves to the last position used when the arm is folded back out, so it doesn’t need to be reset each time.

All of these functions are controlled by a microcomputer that simply plugs into the combine’s electrical circuits, making it simple to remove in the future.

Lexion 750 Mud Hog four-wheel drive conversion

Despite running on tracks, Alan and Andrew felt that the 750 needed to be fitted with a driven rear axle to minimise the risk of getting bogged down in the moss.

© James Andrews

When it was purchased from Claas Eastern, Alan managed to get an old Mud Hog axle from a Lexion 580 thrown in, as it had just been lying around in the yard.

He was told it would be near impossible to adapt it to run on the 750, but he was convinced he would find a way.

The first problem was the attachment point, as the axle was designed to run a 50mm pivot pin rather than the 750’s 80mm.

This was solved by cutting the original section of tube off the top of the axle, machining a larger piece for the pin to pass through and welding it in place.

More of a challenge was adapting the potentiometer that tells the Laser Pilot steering system what angle the wheels are pointing.

This was made all the more difficult by the Mud Hog axle having the track rod on the front, rather than rear of the axle.

To get around this problem, Alan took scores of measurements on the original axle and fashioned an elaborate linkage that made sure the potentiometer gave the same readings in its new position.

Oil flow to the axle was achieved simply by teeing into the hydrostatic oil pipes, although they were a little concerned about the effect the 750’s variable-displacement hydrostatic pump would have on the axle.

Thankfully, it functions like a regular unit in field gears, which is the only time the four-wheel drive is engaged, so they didn’t have any problems.

Finally, a wider set of rims with 600mm tyres was fitted at the rear to give some extra float. These were taken from the old Lexion 630 and had eight-stud centres, rather than the 10 needed for the Mud Hog axle.

Therefore, the original centres were cut out and new ones were welded in place, complete with a set of eyes for attaching dual wheels.

John Deere T560i repaint

A combination of poor paint application, and the fact that it spent its first few years being stored outside, meant much of the metalwork on the John Deere T560i was in a poor state of repair.

© James Andrews

As a result, Alan spent a good deal of time this winter stripping off parts, sandblasting and repainting them.

At least 50 components have been given this treatment on the combine itself and more than 100 on the header.

© James Andrews

“The problem seems to be that they don’t prep the surface properly, so the paint starts to lift at the edges and then flakes off, leaving the bare metal without any protection,” says Alan.

© James Andrews

Claas machines are not immune to this either, with several components and panels on his Lexion 630 and 750 also getting a respray, despite them always being stored inside.

Toolbox improvements

Most combine toolboxes are simply that – a box. To make them more useful, Alan adds shelves with a lip to stop tools sliding out when the door is opened and holders to keep cans of chain lube in place.

© James Andrews

Thoughts vary on whether chains should be lubricated, but Alan is firmly in the camp of making sure they get a good dose of lubricant every day.

Modified hitches

As Alan’s combines often need to tow their own headers, a couple of modifications have been added to make them easier to hook up.

One is an idea taken from steam engines, where triangular fillets are welded into the hitch to guide the ring into position. This means the pin can always drop straight in without doing any additional shunting, plus it reduces the amount of play.

Each hitch also has a stowage point for a dropper pin, a towing ring positioned near the mounting point for additional strength, and a camera to help the operator get into the correct position.

Header end guards

To help prevent fragile header end guards getting damaged by lumps and bumps at the field edge, steel box-section protection bars are welded in place.

© James Andrews

These are subtle modifications that many people wouldn’t notice, but they deflect most of the knocks that can crack plastic or composite guards. Removable front sections have also been incorporated so that the knife can still be pulled out.

Header trailer strengthening

The original Zurn trailer for John Deere’s 25ft header had too much flex in the main beam, meaning the table would bend while it was sitting on it, so much so that the centre wouldn’t be resting on its supports.

Alan therefore set about strengthening it by adding heavy duty box-section braces on both sides.

While he was at it, he raised the ride height – reducing the risk of the header ends hitting the ground – fitted a box for storing cans of oil and made the drawbar telescopic with a coiled lighting cable that extends with it.

Another tweak was to cut the jockey wheel off the jack and fit a wide metal base so that it doesn’t sink into soft ground.

The trailer for his Lexion 750 header has also had a couple of modifications, one of which is a drop-in chock that stops the over-run brakes coming on when the trailer is being pushed into the shed.

Rear marker lights

To help drivers tell where the rear of the combine is when turning in the dark, LEDs have been set into the covers of the rear light clusters.

© James Andrews

These are positioned so that they are picked up in the mirrors, removing any guesswork.

John Deere infiltrates Claas fleet

Having been a staunch Claas loyalist since moving away from BM Volvos in the early 1990s, Alan Johnson broke rank last year and added a John Deere model to his fleet.

This was purely down to the fact the new rep at local Deere dealer Cornthwaites took a chance by stopping in at the field and offered to drop off a demo machine.

“Decent Claas combines were so hard to come by at the time due to shortages in supply so I thought why not, let’s give it a try,” says Alan.

The first machine that turned up was an S-series rotary with a 30ft header, which performed well but minced the straw up too much for Alan’s liking.

They then brought along a five-year-old, five-walker T560i with 25ft header, which was pitted against his similarly sized 2011 Lexion 630 with 20ft header.

“I know the John Deere is a more modern combine, but it knocked the spots off the 630,” he says.

On the back of this performance, and the fact the combine had worked just 280 drum hours, he did a deal to buy it for £170,000, including upgrading to a variable header for oilseed rape. It’s now nearing the end of its prep, ready to get stuck into its first season of proper cutting.

In addition to the John Deere T560i and Lexion 630, Alan runs a 2017 hybrid Lexion 750 with 31ft header, which tends to do the work at larger farms and estates. Together, the trio cuts about 1,100ha a year.