How Arable Insights farmers are using cover crops in rotation

© GNP

© GNP Whether it is to increase soil organic matter, provide grazing for sheep, prevent nutrients from leaching, or deliver extra income within the rotation, cover cropping has become a key part of the rotation on all this year’s Arable Insights farmer panel farms.

Farmers Weekly finds out more about how and why it fits into the system on each farm.

See also: Arable Insights farmers weigh up a future without subsidy

South West: John Farrington

© John Farrington

John Farrington initially began growing six-species cover crops in 2018 to improve soil structure and water holding capacity by increasing soil organic matter.

His use has now morphed into providing grazing for the sheep enterprise he has subsequently built.

That’s changed his focus to making sure the cover crops provide enough overwinter forage for the sheep, leading to both turnip-dominated mixes and six-species cover crops.

“We couldn’t just grow the six species cover crops because we wouldn’t get enough yield,” he explains.

“But with the turnips, you need to hammer the soil a bit more to get the best yield out of the turnips.”

That’s created a balancing act between growing multispecies cover crops to improve soil health, and a turnip mix to provide enough yield over winter to avoid his sheep needing to graze grass until spring.

John Farrington’s cover crops provide grazing for his sheep © John Farrington

“We now do about half and half of each.”

A simple turnip-based mix is about £13/ha, while the six-species cover crop made by mixing single species on farm, rather than buying a ready-made mix, costs about £40/ha.

Last year both were tweaked – adding vetch, linseed and berseem clover to the turnips to add some diversity which, while not improving yield, he hopes will help with soil health.

He also adds a low rate of Westerwold grass to the six-way mix.

“That’s allowed us to graze it up to three times. The first graze takes the broad-leaf species, but then the grass comes back for a second graze.

“Before maize, we were even able to lamb on it, so we’ve had three grazings off it – £47/ha sounds expensive, but if you can graze three times it doesn’t look so bad,” he says.

North: Philip Metcalfe

Philip Metcalfe © Jim Varney

Establishing overwinter cover crops in a timely manner is the biggest challenge North Yorkshire grower Philip Metcalfe faces.

“Generally, they follow wheat,” he explains. “But because we bale all our straw, we have to wait until the buyer has moved the straw and they sometimes don’t show the same urgency as me.”

That can delay drilling cover crops for a week or more, pushing it towards or even after mid-September in some years, which then can coincide with wheat drilling, he says.

With the later-than-ideal drilling, he uses a simple mix of black oats and phacelia ahead of his spring cereals. “We find the phacelia has a decent root mass and seems to keep growing when the soil temperatures drop.”

Where land is rented out for potatoes to a neighbour supplying McCain, a similar mix of black oats, fodder radish and common vetch is grown with the seed supplied by McCain.

Initially, Philip hoped growing cover crops would improve soil conditions in the spring to allow earlier drilling.

Although soils have improved to help make establishment easier, weather is still the dominant factor in when he can drill, he admits.

Covers are either direct-drilled where soil conditions allow, or a light cultivation is used followed by a contractor with a Vaderstad Rapid.

“They can do it quickly and effectively if there is a bit of loose friable soil. We then roll it down tight behind and hope it rains.

“We do need that extra cultivation pass to get more tilth, as it is pointless just throwing the seed about and hoping for the best in that short window – you have to treat it as a crop.”

East Anglia: Jo Franklin

Jo Franklin © MAG/David Jones

Hertfordshire tenant farmer Jo Franklin has been a long-time adopter of cover cropping.

She first saw their potential to feed soil biology more efficiently than making and applying lots of compost during her 2010 Nuffield Scholarship.

After trialling “fancy mixes” versus cheaper and more straightforward cover crops, she’s a firm believer in the latter.

“Other than when we graze them, when the sheep prefer something with legumes in, we’ve not seen any difference.”

Originally, she was growing cover crops to add as much organic matter to the soil as possible.

When that is the aim, she says to watch that the crops are giving you bulk dry matter, as a lot of water can be grown in cover crops

“Simply growing the biggest biomass doesn’t necessarily mean you’re putting more back into the soil that you’re taking off,” adds Jo.

Gradually as the business’s sheep enterprise expanded, the benefits of grazing with sheep started to outweigh not grazing.

“Then it became what holds sheep longest, cheaply, so we moved to more stubble turnip mixes, usually including berseem clover.”

Other species, such as mustard and oats have been grown over the years, but issues with the commercial oats in the rotation have seen Jo moving away from them.

Cover crops are grown before spring crops in a rotation that alternates winter and spring crops.

“That way we’re growing six crops in four years – four harvested, two grazed. We treat our cover crops not as an afterthought – they’re vital to our system.”

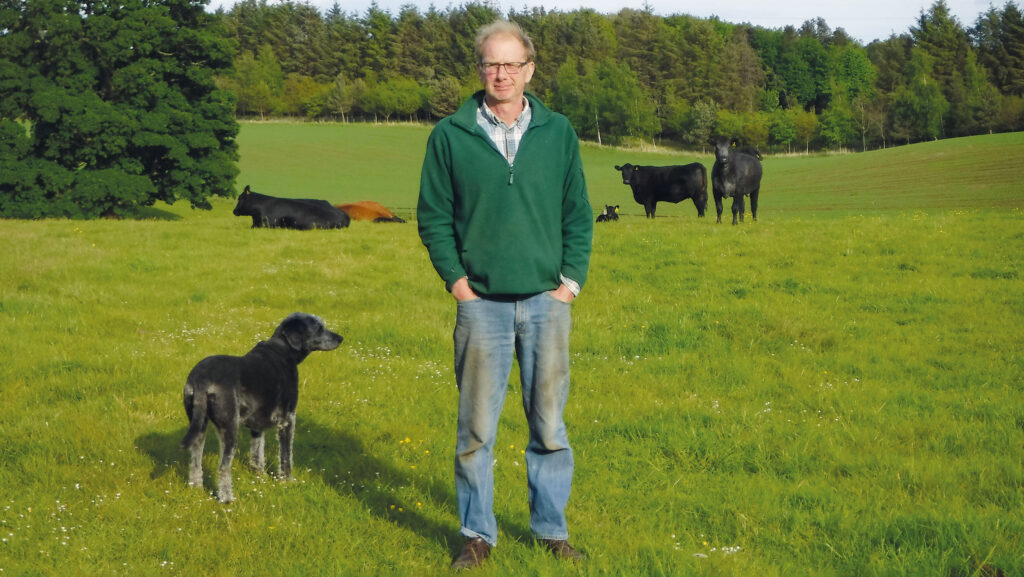

Scotland: Doug Christie

Doug Christie © Supplied by Doug Christie

Growing cover crops, starting with mustard in the early 2000s, was a key part of Doug Christie’s soil health improvement.

He recognised the need for living roots in soils over winter to protect from the effects of rain.

“It can be tricky growing cover crops in Scotland because harvest is so late. But I’m a big believer that having some roots is better than nothing, even if the above ground crop is only an inch high.”

After experiencing some challenges through inadvertently creating a green bridge for barley yellow dwarf virus in spring cereals, Doug now grows a broad-leaf-based multispecies cover crop.

This is usually based on beans, linseed and mustard or radish, prior to cereals, with a cereal-based oats, barley and rye cover ahead of spring broad-leaved cash crops.

“I try to use that seed on the farm because growing a cover crop after the middle of September is hit and miss, and you don’t want to spend huge amounts of money.”

Seed rate is important, he says.

“Put a decent rate in so you get good coverage across the field and treat it well, which is why I direct-drill with a 6m John Dale tine drill as soon as possible after the combine.”

He also grows summer cover crops, although usually only after a crop failure.

“They’re different – I try to get as many species as possible as the legacy effect of a good summer cover crop can be phenomenal.

“There was one field I split in half, and you can still see to the line where the summer cover crop was five years later.”

Living roots from Doug Christie’s winter cover crops help protect his soils from the effects of rain © Doug Christie

Wales: Richard Anthony

Richard Anthony © Supplied by Richard Anthony

Bridgend-based farmer Richard Anthony makes wide use of cover and catch crops across his 1,200ha business to help build organic matter in the soils, which are increasing by 0.2% a year.

Just under 285ha of fast-growing phacelia and linseed are typically drilled as a catch crop to fill the six- to eight-week gap between oilseed rape harvest and wheat, which is direct-drilled into the sprayed-off cover crop.

“We tried mustard, but it’s all top growth, whereas it’s the rooting you get with phacelia,” he says.

Timeliness is a challenge, particularly with slugs proving a challenge after oilseed rape.

That’s meant a change in system away from discs to a Horsch Cultro knife roller to smash oilseed rape stalks and, with it, slug eggs.

“We aim to have that following the combine, then leave the field for three to five days for the volunteer oilseed rape to chit, back in with the Cultro, wait another three to five days, and then in with discs with a seeder to plant the phacelia.

“It’s important we have a clean seed-bed, so we don’t have a problem with slugs.”

Overwintered cover crops before maize are based on forage rye, westerwolds and vetches, which is grazed by sheep until Christmas.

“Forage rye is very underrated as a winter cover crop,” Richard says.

“We plant it in September and, by January, we can find roots down over a metre, which is putting carbon deep into the soil.”

The rye mix is then cut in spring as high-quality forage for local dairy farmers, creating an income stream for Richard, before being finished off with disc cultivation ahead of maize drilling.

“In dry years, we don’t even need to use glyphosate,” he says.

South Midlands: Charles Paynter

Charles Paynter © Supplied by Charles Paynter

To say Charles Paynter is a fan of cover cropping is an understatement.

“It’s the linchpin, the one thing you can do that will make a big difference, whatever your farming system,” he suggests.

He’s been growing cover crops for five years on some fields and seeing some significant improvements in soil organic matter, rising from 4.5-5.5% two years ago to 5.15-7.33% this year.

This is based on a round of soil tests across the farm taken at the same time of year using the same method, in the same place and using the same laboratory.

“I’m struggling to find reasons why to discount the results, although the increases seem high,” he says.

Charles Paynter’s cover crop © Charles Paynter

For overwinter cover crops he uses a variation of a standard Oakbank mix including radishes, clovers and vetches in an eight-to 10-way mix, boosted by the inclusion of white mustard.

“It’s not everyone’s favourite, but it grows in virtually all conditions, even if there’s not much moisture. It’s taken out by frost, which opens the canopy to only need one pass of glyphosate to take out blackgrass.”

He’s found terminating early enough to avoid nutrient lock-up, or soils not drying or warming enough to be important ahead of spring barley.

This also helps with another challenge – not owning a drill that copes with drilling directly into lots of green material.

Charles has found funding under the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) enormously useful in growing cover crops.

“It’s made it much more viable to grow an overwinter cover crop before a spring cereal. It would be much harder without it.”

East Midlands: Colin Chappell

Colin Chappell © Alan Bennett

Making cover crops work on heavy soils isn’t without its challenges, says Lincolnshire-based Colin Chappell, who farms on heavy clay soils.

“But we must make them work. On heavy clay soils it is difficult to get them started, as you need the right conditions.

“But the most important day is the day after you combine, because you have moisture in the soil the previous crop has been sucking up.”

Colin grows cover, catch and companion crops, direct-drilled straight in behind the combine, where possible.

One of the trickiest to make work are overwintered cover crops in front of spring barley, so he finds a cultivation pass after the cover crop is needed to help with spring barley establishment, unlike with spring oats or maize.

Other downsides are slugs, particularly in wet years, if he doesn’t remove straw, and blackgrass not chitting until after the cover crop has been removed.

He has experimented with lots of species, but has settled on a multispecies mix of brassicas, legumes, and other broad-leaved flowering plants to complement volunteer cereals.

The mix includes deep tap rooting species to break up compacted layers and lighter fibrous rooting species, which hold soil in place.

“The more species the merrier,” he says. “I don’t have a limit in price, it’s just what’s good for the crop that’s coming.”

Funding through the SFI and Anglian Water helps lessen any concern about seed costs, he admits.

Foraged winter barley for blackgrass management creates a good window for summer catch crops after the barley is removed in late June.

“These tend to be fast-growing species – mustard, buckwheat and berseem clover, with or without phacelia, linseed and millet.

“The buzz when they flower makes people smile and they’re putting carbon in the soil – it’s a win:win.”

South East: Barney Tremaine

Barney Tremaine © Matt Austin

Sussex farm manager Barney Tremaine will vary how he uses cover crops depending on the crops they are following, how they are intended to be managed, and whether they are funded through stewardship.

“Ones that aren’t funded through stewardship tend to get slurry in the summer, and contain species such as stubble turnips, kale and more radish, so they get a bit more N and have a better crop to graze,” he says.

“Some of the stewardship-funded crops are not grazed until January, so they are more rye, vetch and maybe some linseed, radish, phacelia and clover.

“We then let it regrow before maize, and either work into it or graze again and spray off.”

He also trialled planting maize into high-standing cover of waist-high radish and knee-high oats.

The aim was to see whether, in a strip-till approach, it would retain moisture and keep soil temperatures lower for the establishing maize, as well as potentially providing some weed suppression.

The jury is out on whether it worked. “We got a lot of purpling on the maize, which we think is the brassicas taking a lot of phosphorus out.

“It ended up as a bit of a carpet, which I think probably took a lot of early N from the crop, and then subsequently had a lot of slug issues in what was a very wet spring last year. We even had slug problems when the maize was head high.”

It was hard to draw conclusions, he says. “I think we will continue to trial it, but perhaps with a higher cereal content and fewer brassicas.”