Where now for the tenanted farm sector?

© MNStudio/iStockphoto

© MNStudio/iStockphoto The Annual Agricultural Land Occupation Surveys for Great Britain 2024 confirm once again the dearth of new opportunities to rent farms and land, and that more than 90% of new lettings are of bare land.

The survey closed in October 2024, before inheritance tax (IHT) reliefs were slashed by that year’s Budget and which have since been revised several times.

It is up for debate how the series of changes to IHT announced over the past 15 months might alter landowners’ attitudes to letting: on the one hand letting land devalues the land for IHT purposes, although the terms influence the degree of reduction.

See also: Advice on tenancy matters

On the other hand, the Tenant Farmers Association (TFA) is hearing of land being taken back in hand in anticipation of future IHT liabilities, unencumbering it and making it easier to sell or put to alternative uses to raise cash.

Other landlords are deciding to reduce term lengths offered to tenants who were anticipating renewals of leases on a long-term basis, so that those farms are more readily able to be sold if a tax charge is incurred, says TFA chief executive George Dunn.

Investment fear

A further fear concerning let land is that investment in infrastructure, drainage and general repairs and maintenance will suffer, to avoid enhancing the value of farms against which tax will be due.

“All of this will damage resilience, productivity and growth within the agricultural industry, particularly its let sector,” says George.

Agents report that some landlords, particularly of small and medium-sized estates with relatively small let farms and often a heavy let residential element, are finding the investment requirements for maintenance and improvements challenging, despite that investment being needed to enhance the earning capacity of those holdings and, in turn, the rent roll.

© GNP

Open question

The influence of changes to the IHT regime on lettings is an open question, says Central Association of Agricultural Valuers secretary Jeremy Moody, after 30 years of area-based payments have reduced activity.

The potential challenges as the new policies unfold point to the value to farming of using the flexibility and assurance that farm business tenancies (FBTs) offer, he says, opening up change and opportunities for proficient farmers, existing and new, to secure the use of land.

Jeremy points to the lag which usually follows policy changes and to other influences on letting decisions.

Currently these include three poor arable seasons (although acknowledging big regional variations), the increasing capital requirements of farming in hand, the loss of BPS and the volatility of markets, weather and climate all increasing the risk of in-hand operations.

One source of new lettings may be retiring farmers who want to retain the land. “If you want to retain land, then letting should be considered,” says Jeremy, pointing to the reduction in working capital requirements and the reduction in risk that letting offers.

“It’s important for people to see it not as a retreat or a negative move but a positive one. If we are to secure an increase in productivity then the let sector is a pretty key tool to do it.”

Mark Charter is head of estate management at Carter Jonas and says landlords are caught between wanting to give longer tenancies of seven to 10 years (or longer for some – mainly institutional landlords) so that tenants are incentivised to look after the land or the holding – maintaining the nutrient status of the soil and keeping fences, hedges and other assets in good condition – and the flexibility offered by shorter terms.

In-hand farming losing appeal

“In favour of letting is the challenge of current in-hand farming profitability – the desire of landlords to go in-hand farming is not great. In contrast to getting a rent of £120-£135/acre, it would be a brave move to go farming given the working capital requirements and the rising cost of inputs.”

Mark says landlords he works with are generally re-letting when land comes vacant, although investment is a problem, especially in the case of domestic properties.

In some cases, non-core and surplus cottages could be sold off, he says.

In others, where there is a generational change in the estate ownership, this could trigger land or farm sales if the incoming generation does not have an interest in farming.

Then capital investment requirements, compliance and regulation issues, and a less favourable tax regime may swing decisions.

Local authority uncertainty

The forthcoming reorganisation of local government in England will see the two-tier system of county and district councils subsumed into fewer, larger unitary authorities.

There will also be more regional mayors, with powers over planning, environment, housing and transport.

These changes aim to streamline services, reduce administrative costs, and boost financial resilience.

However, with the local authority sector under huge budget and financial pressure, the restructuring raises questions for the future of county council farm estates, says Mark.

Appetite for let estates

Institutional investors remain keen to buy tenanted farms and estates or land for letting, says Mark, with some colleges and charities taking a long-term view (on capital growth) of 50-100 years.

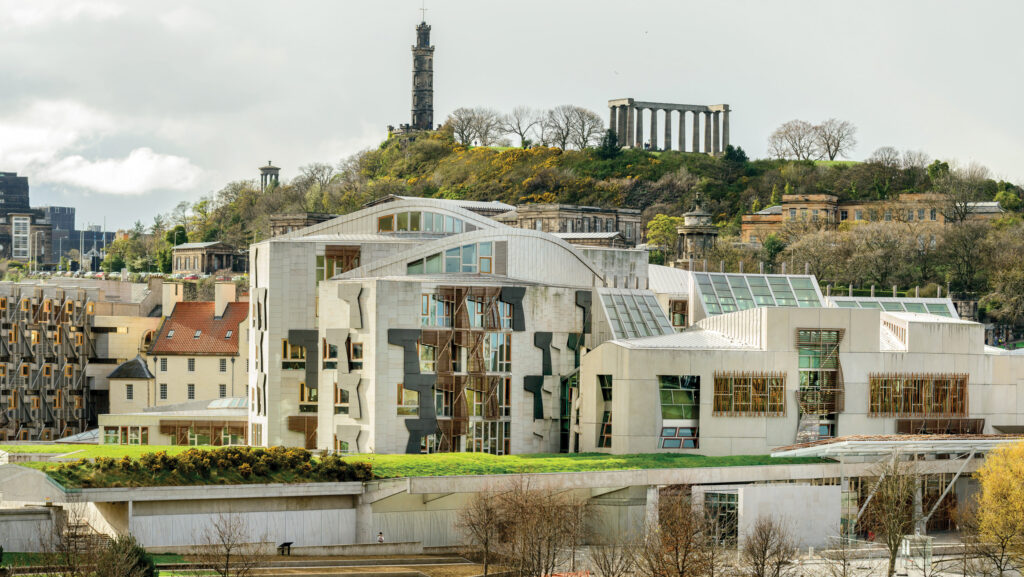

Scotland

Scotland’s tenanted sector has shrunk to just 20% of the land holding, compared with about 35% in England and Wales.

Until 1995, Scotland had a similar proportion of let land to that in England, but now has the smallest proportion of let land of the European countries with a significant let sector.

The survey shows that, as in England and Wales, most Scottish lettings are of bare land, rather than equipped units.

While the 2024 report details 75% of let holdings that fell vacant being re‐let, it states: “With very little new land attracted to the sector, there is much more risk of further decline than opportunity for growth.”

It says nothing seems to encourage private landowners in Scotland (including retiring farmers) to offer land on a tenancy – ultimately the only source of land for a growing and vibrant let sector to be achieved. “In effect, the system is in palliative care while it declines,” says the report.

© Adobe Stock

At land agent Bell Ingram, managing partner Mark Mitchell says that where farmland comes vacant, it is generally not being re-let but taken back in hand to either farm themselves or through contract farming arrangements.

This is due to a combination of factors including several rounds of land reform over recent years, which has reduced the control of landowners over their asset.

“Some short limited duration tenancies are being set up, but these tend to be on relatively small areas of ground and relatively short term, of up to five years,” says Mark.

The latest Land Reform Act received Royal Assent in December 2025, although the enabling legislation is awaited and this is anticipated to take up to two years.

In the meantime, Mark says, landowners want to keep as much control as possible until they see how the new legislation will work on the ground.

“There are a number of things at play – the inheritance tax changes and land reform, including the right to buy, which has mitigated against letting,” he says.

TFA presses on with fairer IHT campaign

The Tenant Farmers Association (TFA) began a campaign in 2015 for more favourable tax treatment of land let for at least 10 years.

It is calling for landlords letting for 10 years or longer to be able to add the value of that land into the zero rate band for IHT purposes.

Incentivising longer-term agreements would also sit well with wider government policy on rural economic growth, farm resilience, farm profitability, food security and the provision of public goods, including in respect of environmental management and carbon sequestration and storage, it argues.

Lobbying against IHT on share of joint tenancy

While joint tenancies are relatively rare, where a surviving joint tenant inherits a deceased person’s share of a joint tenancy, the value of this is subject to inheritance tax (IHT), even though the beneficiary usually has no opportunity to realise the value of that share.

To date, such interests have been relievable either through agricultural property relief or business property relief. However, from April 2026, this value will be 100% relievable only if it falls within an individual’s £2.5m allowance of qualifying agricultural and business assets.

Thereafter, the value will be subject to relief at only 50%.

Lobbying to point out the unfairness of taxing an asset whose value cannot be realised continues, most recently with Tenant Farmers Association (TFA) chief executive George Dunn writing to Treasury secretary Daniel Tomlinson, calling for the value of any joint tenancy inherited on the death of one or more tenants to be excluded from IHT.

“Given that in most cases it will be impossible for the surviving joint tenant or tenants to realise the value of any inherited share of the tenancy on death, it is patently unfair that a tax charge should be levied,” he says.

The unfairness is underlined by the fact that an imputed value for the share of the joint tenancy would have to be calculated on a basis which is, at best, a theoretical value, he says.

The TFA argues that such situations should be excluded from any liability for inheritance tax where the joint interest was held under a contract of tenancy made in a transaction at arm’s length between unconnected parties or at full value between connected parties.

The value of tenancies for IHT is a bigger issue in Scotland, where assignable tenancies, generally 1991 Act agreements, offer the scope to assign the tenancy to another person.

IHT is not a devolved matter and the Westminster government is understood to be looking at this issue.

It is argued that if the value of a tenancy in Scotland is to be removed from the IHT net, that should also apply in other UK nations.

George describes the incidence of joint tenancies in England and Wales as not significant in the overall picture, but the potential financial impact on the surviving tenant is significant. With the Finance Bill due to complete by 26 February, he says there is time to accommodate this and other changes.

CAAV survey findings

The Central Association of Agricultural Valuers’ (CAAV) most recent survey gives a detailed picture of changes in let holdings in 2024, which is described as a “quieter” year, with data for tenancy changes on 830 units.

This is a considerable reduction from the 2023 survey which reported 1,452 units, itself an increase compared with other recent years.

The survey records decisions about land occupation that were then implemented in the year to 31 October 2024 in England and Wales and to 30 November 2024 in Scotland. The key points include:

England and Wales

- The overwhelming majority of lets were for short terms and on bare land.

- A marginal fall in the tenanted area, a net loss of 2,355 acres.

- Fresh lets were marginally outweighed by losses from sales and let land being taken back in hand. This compares with an average annual gain of 35,000 acres between 1996 and 2003 and annual losses before the 1995 tenancy reform of 60,000-90,000 acres.

- 2,116 acres of farm business tenancy (FBT) lettings were on land not previously let, remaining a small fraction of new lets.

- About two-thirds of the 1986 Agricultural Holdings Act (AHA) tenancies that ended with no successor were re-let as FBTs, with an average length of 7.4 years. Just over 8.2% were sold, while more land was taken in hand or for other arrangements, although there was no evidence of significant loss of acres to environmental uses.

- The slow fall in the number of AHA tenancies has tailed off, with numbers fairly consistent since 2004.

- The average agreed length for all FBTs was 3.97 years, a slight rise compared with 2023; for those longer than a year it was 5.05 years.

- Holdings with a house and buildings were let for an average term of just over 10 years.

- Only 10.7% of lettings were of fully equipped farms.

- Very few sales to sitting tenants.

- Tenants perceived as new entrants secured 10% of all lettings – and 29% where the change in tenancy saw a new occupier.

- New entrants tend to be offered longer tenancies – 64.7% of all lettings to new entrants were for a term of more than five years.

- Three successions to AHA 1986 tenancies were recorded in 2024, covering 772 acres.

- The average term of new contract farming agreements, at 2.63 years, was longer than typically seen, with eight units on a three-year term, three units at five years and two at 10 years, across an average area of 246 acres.

- 89% of grazing arrangements were for one year or less.

Scotland

- 2024 saw a further loss from the let sector – a net reduction of 4,235 acres, though less than the much larger losses of a decade ago.

- 75% of the let holdings that fell vacant were reported as re-let, slightly higher than in some of the previous five years.

- Just 1,345 acres of new land entered the let sector.

- The average size of a new tenancy increased to 307 acres.

- The average length of a new tenancy rose slightly to 4.31 (Scottish tenancy law does not permit new lettings of between five and 10 years).

- 78% of lettings in 2024 were of bare land.