Shrinking opportunities for council farms

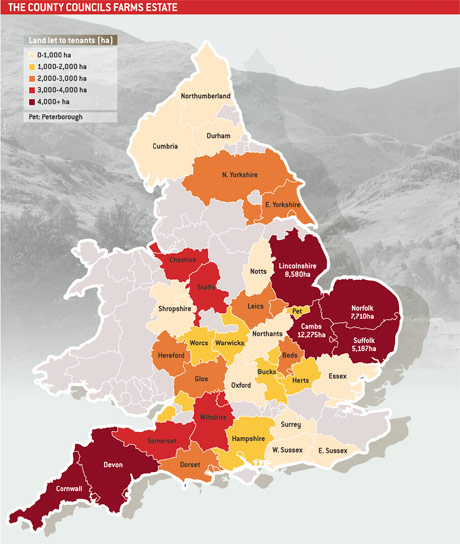

Opportunities are shrinking for new entrants hoping to farm the 99,900ha of county council farmland in England.

Between 2003 and 2007 the amount of council farmland fell by 20%, and claims the Tenant Farmers Association many council landlords are giving their tenants little chance to make a success of their farm before terminating the tenancy. The watchword in many councils is make money quickly, or get out, says the TFA.

County farms originated in smallholding and allotment legislation that pre-dates the World War I, but owe their modern form to the 1970 Agriculture Act. It states that county and unitary councils, in their role as statutory smallholding authorities, are to “make it their general aim to provide opportunities for persons to be farmers on their own account by letting holdings to them”.

George Dunn, TFA chief executive, says that too often councils ignore or sideline their responsibilities. “Without council farms there is basically no route into agriculture for people who want to farm on their own account, rather than working with contractors and large corporations,” he says. “But the objective is wider than just giving people an opportunity to farm on their own account; it also involves sustaining new farmers and helping them to grow towards buying their own farm or taking on a private sector tenancy.

“We are gravely concerned that some councils give tenants only a short period of time and then say that if you haven’t succeeded quickly then you get kicked out. That is a very narrow view of what county farms are for.”

Short-term tenancies – typically of five years – put impossible pressures on tenants, says Mr Dunn, who has launched fierce public denunciations of authorities like Devon County Council. Devon responded by saying the TFA may have misunderstood its letting policy, but promised a rethink.

Herefordshire has also felt the heat, after controversial plans to sell a 160ha slice of its 2100ha estate.

The TFA view has won powerful backing. Last November Sir Don Curry published his DEFRA-sponsored report into the importance of county farms to the rural economy (News, 21 November).

Sir Don concluded that: “It is not sufficient to only offer opportunities for new entrants to come into the industry if they cannot then make the transition on to larger holdings in the public or private sectors,” adding a call for public and private sector to provide a more integrated approach to farming.

The report also slammed the continued disposal of council farms by cash-strapped local authorities, saying that disposals at the current rate will be “a major blow for the future of the agricultural industry”.

Pressure to sell

Councils have defended themselves, saying they are doing their best despite tight budgets and growing pressure to sell land to help fund other services like education.

North Yorkshire is among the most enthusiastic sellers of county farms. Since 1998 it has raised £30.8m with a further £7m in the pipeline for 2008/09. About 2180ha has been sold, more than half to sitting tenants.

Carol Wood, North Yorkshire’s corporate portfolio manager, says the council recently reaffirmed its disposals policy. With an average North Yorkshire county farm amounting to just 35ha, and much of their remaining land fragmented, it could not reverse the sales policy even if it could afford to, she says.

“We have to compete for resources alongside all the county council’s other services, and the council has set its priorities. There are big constraints on spending,” she says.

“Although we are sticking with the policy of progressive disposal, there is no deadline by which they have to be sold. In the meantime we are adopting greater flexibility on diversification, amalgamations and disposals. We want to manage effectively and efficiently.”

In some counties the farm estate is larger and so easier to defend. Cambridgeshire’s 13,900ha estate is the largest in England & Wales, and says rural estate manager John MacMillan, it enjoys the benefits of economies of scale.

“We have a lot of land, which means lots of opportunities for tenants to move into and around our estate. We amalgamate farms where we can into more economic units, and we understand that in the arable sector it takes a good few years to get money out if you have to improve the soil,” he says.

Cambridgeshire has £4.5m to invest in improving its estate over the next five years.

Brighter future

In some counties, where estates are smaller, political skill is helping to preserve the county farm service. By making the county farms relevant to other council priorities, particularly education and environmental services, the county farm service has made friends among senior officials and politicians.

In short, say insiders, if the county farm service makes friends it is able to influence political decisions. And because it is not isolated from other council services, it is much harder for politicians to single it out for budget cuts.

Gloucestershire’s soon-to-retire head of property services Charles Coats explains: “If you are making sure your service is relevant to the county’s other services you strengthen your case, and then the secret is to promote good news stories, to show how the council’s investment is paying off.

“What we have tried to do is to demonstrate the benefits of county farms beyond current tenants. That means we make sure our footpaths are good, we encourage school visits, work on biodiversity plans, and where we can, we make land available for affordable housing, fire stations or schools. It nibbles away at the odd acre here and there, but it shows we are playing our part.”

Other councils are following Gloucestershire’s example. Hampshire is soon to complete a review of its county farms policy, says rural services manager Robin Edwards. “We want to see what else, apart from bringing people into agriculture, a county farm service can do for Hampshire.”

But he warns that carving a more secure place for farms in county council budgets will come at a cost. “If we allow tenants great longevity on our estate, then inevitably you shut the door to some new entrants. The payback for that is that county farms help deliver on other services like education, climate change and biodiversity.”

| Case study 1: Chris Aspden, Warboys, Cambridgeshire |

|---|

|

Chris Aspden won a county farm tenancy at the second attempt. “It was a real challenge,” says Mr Aspden, who now has a 15-year FBT on 223 acres of wheat, rape, sugar beet and potatoes at Warboys, Cambridgeshire. “The council knew what it wanted, and I had to put everything I ever worked for into this to raise the money.” Mr Aspden, 33, worked his way up from farm worker, through to farm manager, picking up certificates in crop protection and level 1 and 2 NVQs. “I tried for a county farm in 2007, but didn’t get in. But I kept on going because I knew that was what I wanted to do, and because there was no other way into farming. I just couldn’t afford to buy, and that is true of a lot of younger farmers,” he says. Mr Aspden, who took possession last year, says the buildings were in good condition, but small for modern machinery. He is now renting extra storage space. “We are now waiting for the first harvest, but the aim is to become more specialist and move away from wheat into root crops, onions and leeks, because there is more margin there, and more of a challenge,” he says. The first lease review is due in three years, by which time he predicts turnover of £500,000. |

| Case study 2: Paul Westaway, Dymock, Gloucestershire

“Never in a million years,” laughs Paul Westaway. “Without a county farm tenancy we’d never have got into farming.” For Mr Westaway, whose Aberdeen Angus graze 130 acres of Gloucestershire county farmland at Dymock, taking on a council farm in 2006 was the only gateway to farming. Without previous experience as a tenant, and without the kind of capital few 36-year-old’s can muster, he rates his chances of taking his first step on the farming ladder without a council tenancy at zero. Mr Westaway has just taken on another 50 acres of Gloucestershire council land, is diversifying and planning for the future. “One thing is for sure, you can’t be Billy Average Farmer and run a county farm,” he says. “You have to add value and be enthusiastic. But we love it. My wife and the girls will be out feeding the cows tomorrow and before long we’ll be moving on to a bigger farm. We wouldn’t have had any of that without a county farm to get us started.” |

|---|

Shrinking fast

The national county farm estate is shrinking fast. Latest figures (for the year ending 31 March 2007) show a net loss of 1657ha taking the figure to 99,900 ha. That represents a 20% fall in four years, whereas between 1984 and 2003 the landbank fell just 9.6% (from 137,664 ha).

Since 1966 the total number of local authority smallholdings in England has fallen from 12,882 to just 3138 – a dramatic 76% reduction.

More than 70% of today’s county farms are less than 40ha, and about 40% are 20ha or less.

The entire county farm estate generates rent of £20.4m a year but costs £10.9m a year to maintain and manage.