Subsidy withdrawal: Efficiency rules in New Zealand

Farming in New Zealand changed irrevocably in November 1984. That was the month the country’s new government, faced with a financial crisis, decided to end all direct support payments to its farmers with virtually immediate effect.

Twenty-five years later there is no question, New Zealand agriculture is better for it. Its farmers have a much greater understanding of their market opportunities, and have developed farming systems to exploit them effectively.

Agriculture, along with tourism, is the industry that drives the country’s economy, making up about 17% of New Zealand’s current gross domestic product.

In the main, it has a good climate for agriculture, with decent amounts of sunshine and rainfall, boosted by irrigation where necessary, and reasonably fertile soils. As a consequence the country can base its agriculture around a low-cost, efficient pastoral system.

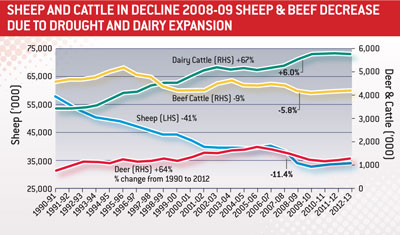

Prior to subsidies being scrapped, sheep farming was dominant. At its peak there were more than 72 million sheep in the country, now it is just 32 million. The price supports, particularly the government-backed minimum prices for lamb, encouraged production with little regard for market or profitability.

Ending subsidies meant farmers produced for the market and, as a result, sheep numbers have fallen dramatically – but prices have gone up. And while head numbers have reduced, improved per-head performance has offset the loss in total meat production to an extent.

Those productivity gains are reflected in most sectors across New Zealand’s agriculture.

“The sheep and the dairy cows are basically supercharged,” said Charlie Graham, the former managing director of ANZ Rural bank. “The application of science in improving genetics, the performance of stock and pastures, the development and refinement of plant management systems and the use of technology has led to incredible productivity gains.

“The result has been the GDP for agriculture has grown by 110% in the past 20 years, compared with just 61% for the wider economy. And it has been achieved off 20% less land area.”

Within that growth there has been one significant trend: the rise of dairying to where it has overhauled sheep and beef as the number one sector.

When you look at the real profitability of each sector it is not hard to see why there have been a large number of conversions into dairying. “Depending on where you are, you can make an operating cashflow of NZ$4,000/ha from dairying after farm working expenses. Arable cropping makes NZ$1,500/ha, and for the sheep and cattle sector it is NZ$800/ha.

“So if you live in country suitable for dairying, you’ve seen a significant shift to that industry over the past 20 years,” Mr Graham said.

An obvious example of the progression of agriculture in New Zealand is the province of Canterbury. Over the past 20 years it has been transformed through the efficient use of “dryland” overhead irrigation, with water drawn from the immense groundwater system under Canterbury or from the great rivers falling from the mountains and dissecting the plains.

Traditional dryland farming systems used to revolve around two pasture flushes to finish lambs for slaughter, Mr Graham explained. “That system used to generate a total farm income of, in today’s terms, about NZ$500-600/ha, and arable farmers on dry land revolved their cropping around cereals, ryegrass seed and peas.”

Traditional dryland farming systems used to revolve around two pasture flushes to finish lambs for slaughter, Mr Graham explained. “That system used to generate a total farm income of, in today’s terms, about NZ$500-600/ha, and arable farmers on dry land revolved their cropping around cereals, ryegrass seed and peas.”

In 1982-83, there was just 20,000ha of dairying; now it is 10 times that, driven by the take-up of overhead irrigation, plus improved pasture management, silage production and nitrogen use.

“Overhead irrigation changed everything,” said Mr Graham. “It allowed the expansion of dairying, with incomes generated of NZ$8,000/ha. Arable farmers have been able to intensify by diversifying into crops, such as high yielding small seeds, as well as continuing with the traditional crops.

“And they can diversify again. If you can get that main crop off early enough, you can also sow a winter feed crop and finish lambs and get two lots of revenue from the farming operation, generating NZ$3,500-4,000/ha.

“While there is significant capital investment involved in irrigation, those income levels leave you in no doubt about the economic benefits.”

Indeed, dairying has been so successful, there is some concern whether it will encroach too much into the arable areas. “It is starting to move on to some of our better soils, where dairy farmers can get good production, and is putting pressure on land availability,” said Barry Croucher, an arable farm consultant in mid-Canterbury.

“But with New Zealand being primarily a niche and targeted market for seed multiplication for export, rather than a large producer of commodity crops, I think we should be able to continue with a good arable industry by targeting those opportunities.”

Unlike most countries, export is the primary market for virtually all New Zealand’s agriculture sectors, with 95% of dairy, 94% of lamb, 87% of beef, 90% wool, 96% venison and 95% of the country’s kiwi fruit exported.

But in the past 20 years the markets have shifted. While the traditional market of the UK is still important, particularly for lamb, they have been augmented by China and south-east Asia in certain sectors, including dairy.

“Those markets continue to grow significantly, along with some diversification into Latin America and the Middle East,” added Mr Graham.

Part of the success in marketing into those areas has been the strong co-operative model, allowing New Zealand’s farmers to share in the value of the product generated on supermarket shelves.

Fonterra, formed in a merger of four co-operatives in 2001, is the poster child for all co-operatives. It is 100% owned by the producers, who own shares based on production. Its fully integrated supply chain with its transparent pricing policy, efficiency and ability to create value in the supply chain have been central to its success.

Innovation, a common trait seemingly within New Zealand’s agriculture sector post-subsidies, is another key attribute, which is why Fonterra has invested in the largest dairy research facility in the world in Palmerston North.

“If you’re going to be exporting 90% of your production, you’re not going to be putting it in a bottle and selling it, like most dairy producers can,” explained Nicola Shadbolt, a director of Fonterra.

“Our customers are all around the world, so there has been a lot of ingenuity to find out what else can you do other than take the water out. Our researchers have two tasks – to increase our efficiency within New Zealand in transporting and processing and to find what else milk can be turned into, or what can be pulled out to create opportunity for our customers around the world.”

Examples of the latter were using a dairy product to create the buttery taste in popcorn and a thickener for yoghurts. Both previously came from non-dairy products, Prof Shadbolt said.

“It is about pulling out what can deliver the requirements of our customers.”

It is a mantra that the whole New Zealand agriculture sector appears to have grabbed.

Future challenges for New Zealand agriculture

• Attracting new people into perceived “sunset industry”

• Investment in research and development

• Environmental management: nitrogen, biodiversity, market perception

• Rewarding good stewardship

• Moving to low-emission agriculture

• Adopting new technologies needs good IT infrastructure

Case study: Doug Avery, Bonavaree Farm, Marlborough

If any farmer demonstrates how New Zealand farmers can develop innovative systems, it is Doug Avery.

It was not just the changing economic environment he had to deal with, but the climate too. His 1520ha dry land, hill country Bonavaree Farm in Marlborough on the South Island, runs 3800 pregnant ewes, 600 dry sheep, 900 beef cattle and 400 dry dairy cows, and is in one of the driest parts of New Zealand.

“It is hot, dry country. In the 90s we had eight consecutive years of drought, and 17 of the past 19 years below average rainfall. Something had to change.

“I was challenged to produce a farming system, that would be resilient in the face of extreme weather and variability, miserly with the water and conserving of energy, and highly profitable in good years while not losing money in bad ones.”

The answer lay in changing his grazing from a ryegrass base to lucerne, and moving to a 10-month farming system. “We can’t influence the weather, but we can influence how we use our limited water and grow plants that use that water efficiently.”

According to Lincoln University research in New Zealand, lucerne can double the amount of dry matter produced using ryegrass on a hectare from around 250mm of water in the spring..

“It gives us quality feed when we need it,” Mr Avery said. Since sowing half of the farm with lucerne in 2005, he has consistently produced lamb growth rates in the top 5% in New Zealand and improved his hogget scanning from a disastrous 40% to 162%.

“The reward has been a system that has given stock performance we could only dream of a few years ago and produces profits, despite variable rainfall.”

Subsidies: why were they all scrapped?

For more than 20 years up to 1984, there was a steady increase in the level of support given to New Zealand’s farmers, although a full programme of subsidies was only introduced in the 1970s.

That was after the country’s balance of payments plummeted as a result of higher global oil prices, Bruce Ross, the former vice-chancellor of Lincoln University, said.

In 1984, nearly 40% of the average sheep and beef farmer’s gross income came from subsidies. “It was clear the government’s minimum prices, which made up the difference from world prices, were out of line with market reality.”

At the same time, the whole economy was struggling, and in May 1984 the government presented a budget that proposed a fiscal deficit of 9.5% of GDP, which seemed horrendous, said Prof Ross.

Shortly after, a new government was elected and it presented a new budget in which the major feature was the removal of most forms of support to farmers. “Farmers were told the assistance provided by the devaluation [in currency] would replace the cash support payments. Not only did this reduce the pressure on the budget, but also removed the distortions provided by the support payments.”

But it was a painful process, and part of the restructuring of the whole economy, Prof Ross stressed. Inflation and unemployment rocketed and interest rates followed, peaking at more than 20%, while land and house prices fell and unemployment rose to 11% by 1991.

“For farmers, it became tough to get credit and there was a substantial loss in equity. The pain was felt most keenly by those who were most indebted.”

But official predictions of 8,000 farms failing were wide of the mark, according to Federated Farmers of New Zealand information. In fact, only 800 farms, faced forced sales in the end. And a much more dynamic, successful farming sector has emerged from the years of hardship.

Opinion: Mike Abram

It is not until you go to New Zealand that you realise just how different its farming is from ours. On the face of it, our climate seems similar and we have, in the main, similar agriculture sectors.

But dig beneath the surface and it becomes clear New Zealand operates in a very different environment. Exporting virtually all their agriculture production has led to an intense focus on exactly what its customers want, a vision only sharpened by the absence of subsidies.

It has made its farmers into extremely business-focused operators, with a keen eye for opportunity and innovation.

Whether UK farming would be better off subsidy-free is difficult to extrapolate. Our farmers operate in a very different market environment to the almost exclusively export-focused Kiwis, and the likelihood is the sudden removal of subsidies here would create untold hardship, just as happened in New Zealand 25 years ago.

But if we can learn one thing from New Zealand, it would be to bring that hard-edged business focus to more farms in the UK.