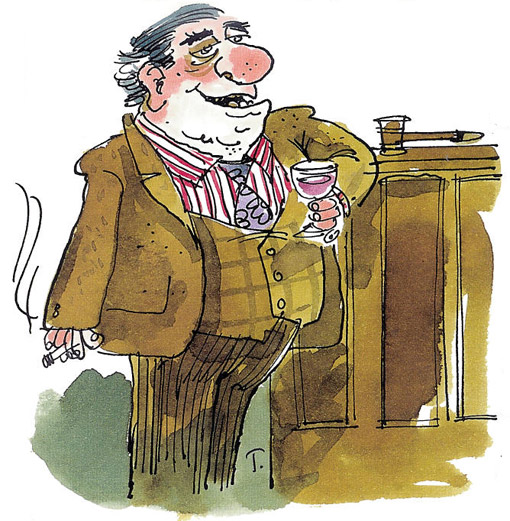

Farming Breeds: Angus Tuppings – the auctioneer

Join us for a funny, irreverent look at some of the characters that make the British countryside what it is. Our tongue-in-cheek guide puts characters such as the retired Major, the “perfect” next-door farmer and the young tearaway under the microscope. Here we meet Angus Tuppings – the auctioneer, with a keen eye for conformation…

The auctioneer likes his steak rare. “So rare it’s almost mooing,” he bellows at the waiter. “And leave the fat on – it’s the best bit.”

He’s at some dinner – the RICS, the CAAV or the LAA. And he’s making the most of it, getting stuck into the wine and the port, sinking ever lower in his chair as the evening progresses. His stomach is expanding, his waistcoat stretched to breaking point.

The auctioneer speaks in a dialect that went out of common usage in the 1840s. You hear him as he strides around the countryside, looking like some extra from a costume drama, yelling something incomprehensible about “two-tuths”.

He’s understood by other auctioneers, a clutch of farmers within a five-mile radius of his market and an assortment of farm animals. Not that it matters no one else needs to understand him. And he certainly doesn’t care if they don’t.

He hates veggies, government and anyone involved with deadweight selling. “Markets are the only transparent method of selling,” declares Angus.

The auctioneer loves market day – all the noise, the people, the hustle and bustle. You can hear him coming across the yard at 100 yards, his dealer boots clicking. He’ll be smoking, his check shirt open, the chest hair poking out like ivy on an oak.

The auctioneer speaks in a dialect that went out of common usage in the 1840s. You hear him as he strides around the countryside, looking like some extra from a costume drama, yelling something incomprehensible about “two-tuths”.

He’ll eat with the farmers in the canteen. “Usual, please, my love,” he bellows at Doreen behind the counter. His usual is steak-and-kidney pie, beans, peas, mashed potato (extra large portion) and three slices of bread and butter. And that’s just breakfast.

When he’s not in the mart you’ll find him out in a muddy field of turnips, frost in his sideburns, grading sheep. He’ll have been there since the crack of dawn – he’s the only person in the parish, in fact, who gets up earlier than the farmers.

Angus can tell the conformation of a sheep at 100 yards. He knows what proportion of Limousin a calf is. He knows how much a carcass weighs to the nearest half pound. “And it is a bloody half pound, I tell you – not one of those kilos.”

Angus loves standing up there on the rostrum, surrounded by familiar faces. Gibbering insensibly. Banging his gavel. Cracking smutty jokes about back-ends and well-endowed bulls.

Sometimes he wonders why he’s laughing, though – it’s not a laughing matter with livestock prices the way they are. Low prices mean low commission.

Maybe he should have gone back to the family farm after all – but his older brother did. Still, auctioneering’s a way of life, Angus thinks, tucking into the port.

He’s had a glass too much, in fact, and starts slurring his words. Not that you’d notice – he was incomprehensible before he started drinking.