Flindt on Friday: Dad’s desk secrets and mysterious Mrs Smith

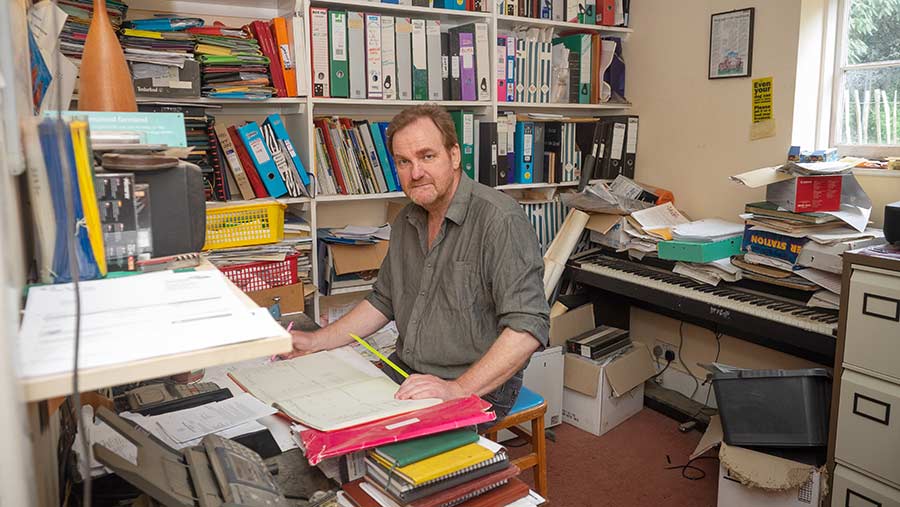

© Kathy Horniblow

© Kathy Horniblow Finally, after years of dithering and indecision, the day came to throw out Dad’s old farm desk. I thought I’d be describing it as a sombre and melancholy occasion, tinged with regret. Actually, we were bloody glad to be rid of it.

Not least because it was hideous – a dark brown roll-top desk from the 1920s, with an engraved brass plaque explaining that it was a farewell gift to the Revd. Someone-or-other from his grateful parishioners.

In 1959, it found itself in a sale, where Dad, seduced by its dark art deco styling, thought it would be perfect in his new office in Hinton Ampner.

See also: Read more of Charlie Flindt’s columns

It was all change in 1997, when my vernacular beech desk moved in, and the old roll-top got shunted to the hall – temporarily.

In these parts “temporarily” can mean two decades, so when a bit of desk-shaped space was spotted in the farm skip in January, we decided the time was right.

It was confirmed as a good decision when the first drawer we opened collapsed in a pile of slightly worrying dust. The quicker it went to the skip, the better.

But tucked away among the slightly decrepit drawers was a fantastic piece of farm history: a wages book starting in 1964.

And I found it astonishing that on a 900-acre mixed farm, 10 wage packets were prepared every week.

Shillings to pounds

The first thing I did was instruct my teenager to find a conversion chart, to change the old pound/shillings/pence figures into a modern equivalent.

He quickly found an ONS figure of £1 in 1964 being worth just over £20 today, so that’s what I’ve used. £200 a week seemed to be the significant figure.

The five core staff all got just above or below that figure (probably best not to name who got more – wars have started in country villages over less).

Dad paid himself exactly £200, Mum got the same for housekeeping. The wonderful Mrs Deb, housekeeper/nanny/all-round saint got £60 – which seemed a bit harsh bearing in mind I was in her care a lot, and that involved me locking her in the cellar a lot (tee hee hee). Horrid little child.

Best paid was an “assistant”, who scaled the dizzy heights of £225 per week. The wage bill for 30 January 1964 came to £84.11s – that’s £1,691 in today’s money.

Mysterious Mrs Smith

I confess I has to sit down and ponder this for a moment. A whisker away from £88,000 a year – where did Dad find that sort of money?

Yes, yes, I know he was a farmer of unfathomable brilliance and all that, but he was only a few years into sorting out a farm that was described (in a “good-luck” letter to him from his bank manager when he started at Hinton Ampner) as “a considerable challenge”. Amazing.

Then my eyes strayed back to the list of pay packets: tucked away at the end of the list was a ‘Mrs Smith’.

She received the princely sum of £1.5s. – or £25 in today’s money. I’ve been racking my brains, trying to remember Mrs Smith from my very remote youth. Who on earth was she? Where did she live? What did she do to earn £25 every week? And, perhaps more importantly, do we want to know?

Any further clues to Mrs Smith’s key role in the running of Manor Farm, Hinton Ampner in the early 1960s vanished into the skip along with the desk, soon buried under an undignified heap of rubbish.

And as the skip lorry headed off to God knows where, I couldn’t help thinking that her secret was quite safe now.